|

Pam Tice, Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group Planning Committee member

Here is a second post in my series exploring Bloomingdale in Colonial times and after the Revolution. Colonial New York New York City’s colonial history provides a context for Bloomingdale’s history before the American Revolution. The City became an economic powerhouse in the 18th Century after Queen Anne’s War ended in 1717. The development of the plantations in the British West Indies to meet the rising demand for sugar drove the New England and the Middle Colonies to become the suppliers of food and other essential supplies for the plantations. New York became, in that time, one of the imperial centers of the British North American empire, the others being Jamaica in the West Indies, and Halifax in Canada. New York City began to lose its original Dutch cultural heritage as the British economic and cultural practices prevailed. Merchants in New York were drawn into the slave trade as slaves were needed to labor on the farms surrounding the city, as well as to work in building ships, handling cargo, and even the day-to-day work of operating businesses. Some slaves also worked as domestic servants. While we don’t have actual headcounts of enslaved people in Bloomingdale until the 1790 federal census, we can be quite sure that many slaves labored for their masters here. An enslaved population was one of the major features of New York City life in the 18th Century. Another blog post in this series will provide more details about slavery in New York City and the details found about enslaved people in Bloomingdale. New York City’s aristocracy was one of wealth, not lineage. The merchant princes of colonial New York became the leaders of fashion, politics, intellectual life, and philanthropic projects. They moved to a life of ease and comfort similar to their peers in London. Their personal fortunes were tied-up in real estate and the elegant homes they built in downtown Manhattan. But soon they began establishing “country seats” up the island along both the East and the Hudson Rivers. Along the Boston Post road to Harlem, the Stuyvesants, Beekmans, LeRoys, and Gracies established estates. In what became Greenwich Village, the Delanceys, Bayards, and James Jauncey established themselves. South of Vandewater Heights—in Bloomingdale—the Apthorp, Striker, Delancey and Bayard estates were established by mid-century.The Delanceys named their estate “Little Bloomingdale.” These estates mixed with the farms that were already well established. Some country seats raised crops for market as well as serving as country retreats. Most estates were what one writer called “theaters for refinement.” Both employed slave labor where the footman who stood behind the master of the house at dinner was a slave, as were the maids and coachman, a colonial version of the gentrified home in England. Gardening and landscaping were important for some, as reflected in the advertisements of the land. Gentlemen were focused on fast horses and fox hunting in Bloomingdale. Downtown, assembly balls, theater and the Vauxhall filled with waxen figures were features of winter social life. Kings’ College and the New York Society Library were founded. Religious life was important but Bloomingdale did not have enough population to support churches until after the Revolution. The merchant princes of Bloomingdale were conservative, and many remained loyal to the British Crown when the Revolution came. Their choice would determine the property changes that came after the War.

0 Comments

This is the third post about 18th Century Bloomingdale, written by Pam Tice, member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group Planning Committee.

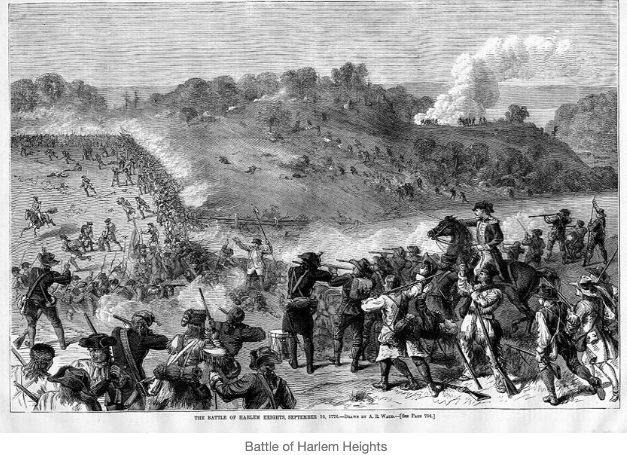

So many historians have written about the Battle of Harlem Heights on September 16, 1776, that I do not need to re-tell the story here. Jim Mackin presented a program about the Battle, centered around the Jones and Hooglandt farms, one evening back in 2019, and then wrote a post about here. There’s a much more detailed description of the Battle here: http://www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/battle-of-harlem-heights/ I’m focusing here on observations about Bloomingdale leading up to the Battle, and the seven years following, when the British had taken over New York City and imposed military rule. This is a fourth post on colonial and post-Revolution Bloomingdale written by Pam Tice, member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group.

Now that I’ve written three posts about Bloomingdale in the 18th Century, I’m turning to the topic that caught my interest initially: slavery in Bloomingdale. As those who research family history know, finding details about African American ancestors is difficult. I had the same problem in trying to find factual information about slavery in Bloomingdale. Census information is available, and I’ll share what I found. Newspaper advertisements for runaway slaves or attempting to sell enslaved people are another source. Church records have some detail. I looked at all of these. I also looked for evidence of African American burial grounds. First, though, I had to understand the history of slavery as it played out in New York City. Scholars have explored the institution of slavery in New York City in recent years in great detail, producing a great number of books and articles. The discovery of the African American Burial Ground in lower Manhattan in the early 1990s encouraged many scholars to pursue the detailed research which has amplified the experience and historical identity of African Americans in our city. Of the books I read on this topic, I found Thelma Wills Foote’s book, listed below, of particular interest. The enslavement of African Americans was prevalent in colonial New York, where 40% of Europeans owned slaves, averaging 2.4 per household. By the 1720s, there were 5740 slaves in New York City, the greatest number of urban slaves outside the South. In 2015, the City recognized this part of its history by installing signage downtown at Wall and Water Streets to mark the 18th Century slave auction block. Under the Dutch West India Company, the first slaves arrived in 1626 and were put to work building the company’s infrastructure and working on the farms that grew the local food supply. Dutch merchants and artisans taught slaves how to handle their businesses, a practice that continued when the British took over the city in 1664. The Dutch extended some leniency: allowing some enslaved people to negotiate their freedom, and to own property. This image of Dutch New York pictures the enslaved people of that era. This is the fifth post on colonial and post-Revolution Bloomingdale written by Pam Tice, member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group.

New York City had to recover from the Revolutionary War after George Washington marched back to downtown Manhattan in November1783. The city became the United States Capital until 1790, when it moved to Philadelphia. Population growth was strong from 1790 to 1820 when Manhattan’s population grew from 33,131 to 123,706, and doubled again by 1830. Bloomingdale grew and changed during this time also. The first census in 1790 shows the property owners: the de Peyster brothers, near where Columbia University is now, the Striker family at 96th Street, Charles Apthorp in the West 90s, the Harsens, Somerindykes and Cozine further south. Moses Oakley and Benjamin Stout, both designated slave owners, are also in the early censuses. My research shows them to be tavern owners, which I’ll cover in a separate essay. The large estates of the Bloomingdale property owners may have had estate managers or workers who were not enslaved, since there are other names listed in the early censuses. These people must have led quiet lives, as there are no newspaper articles or other records that would allow the researcher to identify them. Many historians cite the continuing epidemics of yellow fever between 1793 and 1805 as one of the reasons Bloomingdale’s population grew. No doubt that is true. The frightening outbreaks in downtown Manhattan had a more measurable impact on the development of Greenwich Village. Numerous banks, newspapers, and other businesses moved there along with the post office and the customs office. If a family had the means to do so, leaving the city for the countryside was necessary to avoid what the newspapers often called “the prevailing fever.” Yellow fever developed in many east coast cities, starting in the West Indies, and moving north on ships. New York began to develop its public health response during the 1790s and the first decade of the 19th century; funds were allocated to help families. The Common Council purchased Brockholst Livingston’s 4-acre estate known as Belle Vue, and a hospital to quarantine victims was developed there. Mr. Livingston had an estate in Bloomingdale too, named “Oak Villa,” in the West 90s near Mr. McVickar. By 1800 there are numerous others settled in Bloomingdale. Many slave owners were also property owners. We can identify Robert Kemble, who purchased the Jones estate in 1798. Two additional de Peysters, George and James, joined Nicholas. James was his brother and George was his son. Later, in 1810, Gerard de Peyster, son of James, would be listed. Nicholas’ very large estate, formerly the Adrian Hoaglandt land, was sold off over time to other owners. In 1796 he sold the portion known as Strawberry Hill to George Pollock, an Irish linen merchant, beginning the development of the estate known as Claremont. In 1805 Nicholas de Peyster sold his land to the south to Gordon Mumford, who had served as Benjamin Franklin’s private secretary when Franklin was representing the U.S. in Paris. Mumford returned to New York and became a successful merchant, establishing his country seat in Bloomingdale. John McVicar who owned land in what had been the Delancey estate prior to the Revolution, around West 84th Street, was described as one of New York’s “merchant princes.” Mr. McVickar is remembered for his generosity in offering hospitality to the rector of the new St. Michael’s Church during one of the summer yellow fever epidemics. His land also contained the popular small pond found on early maps where the Bloomingdalers skated in winter. John Clendening, the subject of an previous blog post, settled into Bloomingdale with his property further east, at 104th Street. By 1810, Mr. Jauncey had purchased the Apthorp property, and by 1811 William and Ann Rogers owned the Kemble property. Poor Mr. Kemble became bankrupt with one account of his troubles stating that he was left with only his watch as he settled his debts. Another Bloomingdale property owner, William Seton, also became “a bankrupt” in the late 18th Century. This fate was one of the fears of the merchants of New York, along with the yellow fever epidemics. Before there were laws governing the state of bankruptcy, one could be thrown into debtor’s prison. Mr. Seton died suddenly in 1798 and his son, William Magee Seton, struggled to maintain his father’s business. He sold property, including the 22 acres in Bloomingdale, advertised as between Robert Kemble and Nicholas de Peyster, in the early years of the 19th century. William Magee Seton’s wife was Elizabeth Bayley Seton, the first American to become a Saint in the Roman Catholic Church. Her religious conversion and struggle brought on by her family’s bankruptcy and illness sheds a light on the life of the New York merchants and the precarious nature of their businesses as they brought products into the New York market. Property sales in Bloomingdale reflect a trend of people purchasing smaller country estates. The larger estates of sixty acres or more were now broken into smaller ten and twenty acres or less with land available for cultivation. Very often an advertisement mentions the “respectable New Yorkers” who lived close by, as the de Peysters did in 1807 when advertising a house and land for sale, noting that Governor Clinton had spent the previous summer there. When the City’s first guide book was published in 1807, the area was important enough to mention in a description of the Bloomingdale Road where there were “numerous villas with which Bloomingdale is adorned.” During this time, Bloomingdale’s rural landscape became an attraction for those who owned horses and carriages, where an afternoon drive through the hills and valleys of the Bloomingdale Road brought great pleasure. Later in the 19th Century when circulating the carriage drives of the newly-built Central Park, writers would look back with nostalgia on the pleasures of driving through Bloomingdale. The taverns of the early 1800s, and “watering places” that became the Abbey, Burnham’s and Striker’s Bay hotels were all part of the enjoyment of the countryside so close to the city. Bloomingdale’s buildings and roads were the subject of numerous sketches made in 1875 by Eliza Pratt Greatorex in the folio volume she produced with her sister: Old New York: From the Battery to Bloomingdale. After the Civil War, many of these structures disappeared in the post-war building boom. Thanks to Greatorex, we have these images today. This is the sixth post exploring colonial and post-Revolution Bloomingdale written by Pam Tice, Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group Planning Committee member.

New York City had a “tavern culture” starting in Colonial times. Taverns came in every shape and size and were owned by a range of residents, both elites and non-elites. The City profited from the licenses granted to tavernkeepers, issuing 314 in 1761. Taverns were male bastions where heavy eating, drinking and singing songs took place. Taverns provided a convenient place for politics and even government meetings. Horses and even slaves were advertised for sale through tavern owners. Fox hunts were organized by tavernkeepers in rural settings, like Bloomingdale. The tavern keepers and their taverns described here were found in newspaper articles from the time after the Revolutionary War to the early decades of the 19th Century. Benjamin Stout Benjamin Stout’s name first appeared in the 1790 census, listed next to/near Charles Apthorp and James Striker which clearly put him in the Bloomingdale neighborhood. He was next to Moses Oakley. Both men had slaves, four for Stout, two for Oakley. Who were they? My research found Benjamin Stout to be a tavern owner, but his tavern appeared to be one called the “Plow and Harrow at the Fresh Water” in the Out Ward, placing him in downtown Manhattan. He was licensed in 1758; an article in 1760 referred to him as a “noted tavern keeper.” In his essay on New York’s Loyalists, historian Christopher Minty, in writing about the Delancey family before the Revolution, mentions Mr. Stout’s tavern as one of the gathering places the Delanceys used to build their case for election to the New York State Assembly in 1768, when they tried to win against the Livingstons. I found a copy of Mr. Stout’s will, written in 1783 and “proved” in 1788, naming his oldest son as one of the Executors. Thus it appears that it was the younger Mr. Stout operating a tavern in Bloomingdale in 1790. An April 1791 Daily Advertiser (newspaper) article answered my question: “Benjamin Stout has opened a public house at the place belonging to James McEvers, where every kind of refreshment will be furnished to all who chuse (sic) to regale themselves at that inviting and truly pleasant summer retreat.” (McEvers was Apthorp’s brother-in-law who had died soon after he built his house in Bloomingdale; his property may have moved back to Apthorp ownership.) This is the seventh and last in this series exploring colonial and post-Revolution Bloomingdale written by Pam Tice, Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group Planning Committee member.

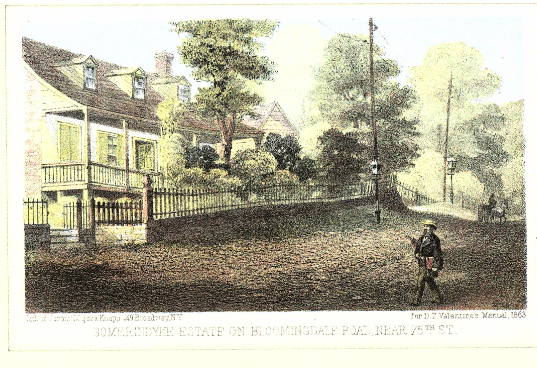

As parents cope with educating their children in this complicated time, it’s been interesting to look back to the late 18th and early 19th centuries when schooling was handled quite differently. It was not until 1842 that the Board of Education was formed, bringing the schools closer to what we have today. This post looks at how children were educated before the emergence of a “school system.” When New Amsterdam was founded, schooling children was the responsibility of the Dutch Reformed Church. When the British took over the colony in 1664, they kept the same practice, keeping the Dutch Reformed Church schools and adding the Church of England’s Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts to oversee education. In 1709, Trinity School, a Bloomingdale School of today, was founded by Trinity Church, the Anglican church in downtown Manhattan. After the War of Independence, the New York Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves established the African Free School for the children of slaves and former slaves; by 1827, that system had grown to seven schools. The Free School Society was established in 1805, modeled on the African Free School. Later, it became the Public School Society. These schools were for poor white children of any religious background whose family was unable to afford private, paid education. These free schools, along with the religious-oriented charity schools, received public funding in 1795 and continuing for a number of years. The stated ideal of the separation of church and state took a while to catch on in the early years of United States. First, public funding of church charity schools was withdrawn. Eventually, by the mid-19th Century, legislation specifically prohibited denominational religious instruction in public school classrooms. It is against this background that educating children in the early years of Bloomingdale can be discovered. The wealthy merchants who established their “country seats” here no doubt had private tutors for their children who taught them in their own homes. The school masters who taught Bloomingdale children had to advertise their services, as reflected in 1794 when Asa Borden took an ad in the Daily Advertiser newspaper announcing that he was continuing as usual in Bloomingdale teaching literature, writing, arithmetic, book-keeping, English grammar, while “paying strict attention to the morals of his pupils.” He promoted the “salubrious situation of the place” that education would be better in the countryside where there were no vices to distract his pupils. He mentions Moses Oakley and James Striker among those who could recommend his services, and offers “genteel boarding” near the school —- although the location is not specific. One of the often-told stories about the West Side is about a tutor—King Louis Philippe of France. When he was a young man, long before he became King in 1830, he had to leave France during the Reign of Terror (1793-94) and supported himself by teaching. King Louis Philippe taught at the Somerindyke residence where Broadway and 75th Street are today. His sojourn in our neighborhood is commemorated in this print from an 1860s Valentine’s Manual. by Pam Tice, member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group

January 17, 2020 was the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the Prohibition era. I’d planned to write a blog post about that era in our neighborhood, especially since we were the site of the Lion Brewery on Columbus Avenue at 107th Street. The 2020 Pandemic intervened and I diverted to the 1918 Flu Pandemic. Now I’m returning to Prohibition in Bloomingdale. Since so much about this time involved illegal activity, it took more digging than usual to find places in our neighborhood where the 1920s era played out. What I found may be merely the tip of an iceberg, revealing only those places that were reported in the newspapers because they were caught breaking the law. If you are reading this and know of a speakeasy operating in our neighborhood in the 1920s, please do let us know! My sources, listed below, include books by historians who have looked at this era, particularly in Manhattan; the newspapers reporting day-to-day enforcement and political activity, and online resources covering Prohibition. This post was written by Pam Tice, a member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group Planning Committee

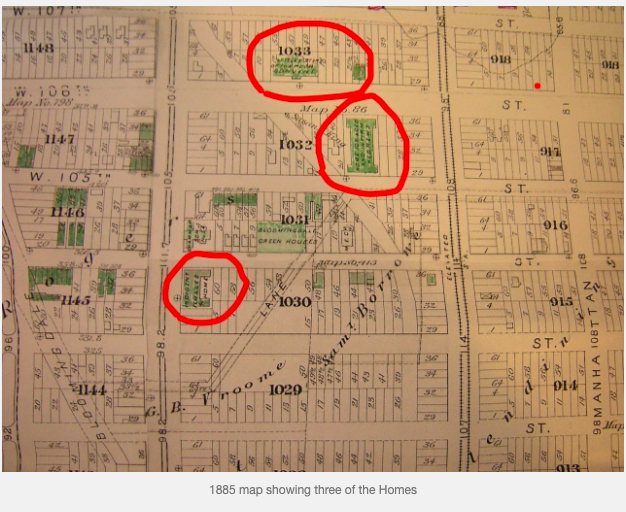

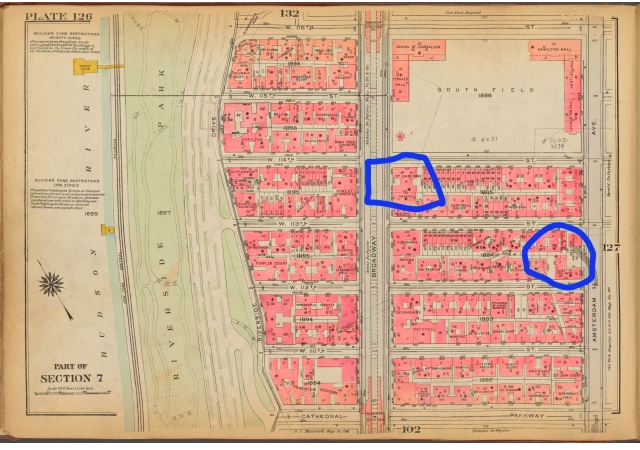

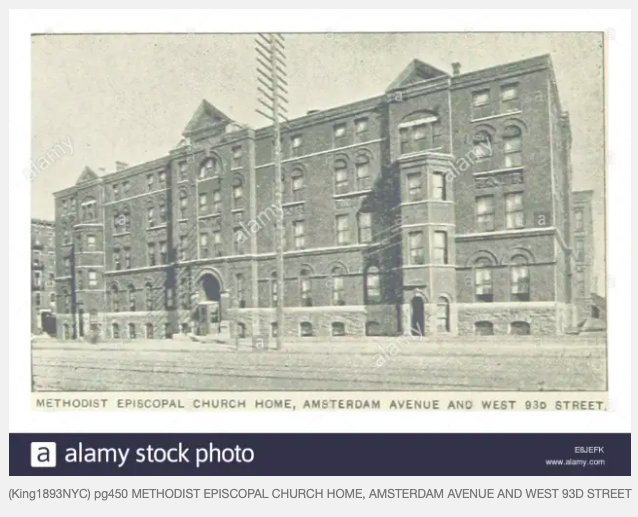

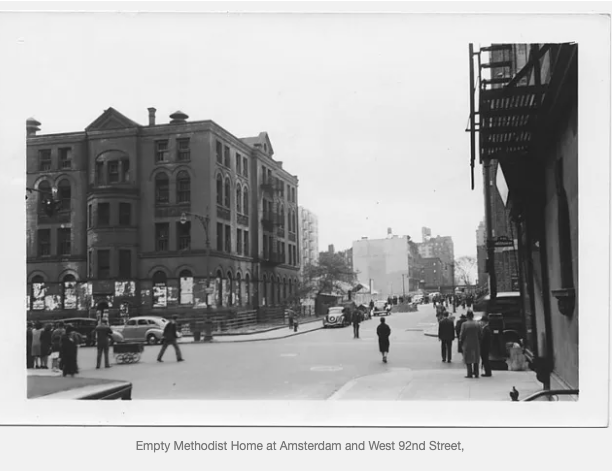

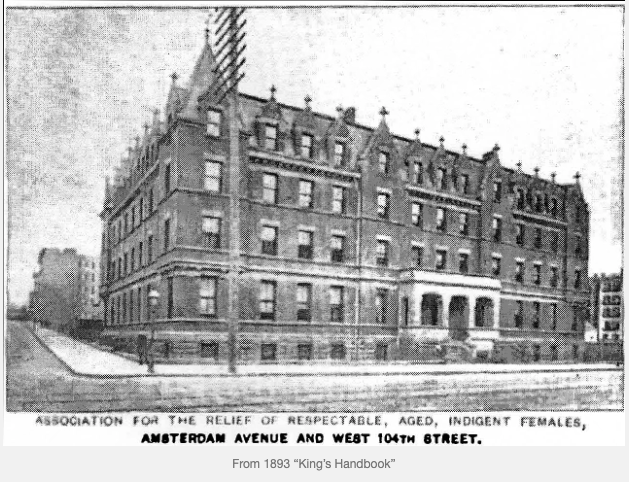

I had a little bird, Its name was Enza, I opened the window, And in-flu-enza. Children’s Rhyme, 1918 As our 2020 Pandemic Spring unrolled over the past few months, there have been numerous articles reaching back to 1918 when the “Spanish Flu Epidemic” spread across the United States. On the 100th anniversary in 2018 historians looked back on that time, most not imagining that we would be re-living this type of historic event just two years later. As I get ready to upload this post in mid-May 2020, New York’s City’s 20,000 + deaths from the Covid-19 Flu are close to matching the number of deaths in the fall of 1918. Back in March when New York went on “pause” I decided to learn about the 1918 flu epidemic in New York City, and then learn how the illness may have played out in the Bloomingdale neighborhood on the Upper West Side. I wanted to understand what local life would have been like at that time. I started with the articles about 1918, focusing particularly on New York City. I looked in the academic journals, and searched the newspapers. My search was all online, of course, as all archives are currently closed. I read all the contemporary pieces where the historians discuss 1918 in light of today’s ongoing event. Nothing I found (almost) related directly to Bloomingdale. Nevertheless, I learned a lot about New York City in 1918. I decided to share what I’ve learned—about the flu epidemic, about the public health and the nursing profession, and about World War l in New York City—and how all of these things might have touched the lives of those living in Bloomingdale. Many who have written about the 1918 flu epidemic—no one called it a “pandemic” then—note how it was barely even remembered. The disease killed 33,000 in New York City when our population was 5.6 million. In the second wave of the disease, the fall of 1918, more than 20,000 New Yorkers died. In the United States, 675,000 died. There are a few written memorials, but, in general, everyone simply moved on after it was over. In his novel “The Plague,” Albert Camus describes the many millions of bodies as no more than an intangible mist drifting through the mind. Many of us today find evidence of the 1918 flu as we research family history, stories of the long-time grief experienced when parents and siblings were lost to the epidemic. The stories aren’t always sad: a recent comment to a New York Times article tells the story of a grandmother telling of the time she woke up in the hospital in 1918, heard the bells of Armistice Day ringing, and thought she’d gone to heaven! This post and the two that follow on the same topic are written by Pam Tice, member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group planning committee. In the early days of the nineteenth century as the population of New York City expanded, how to care for elderly citizens, particularly the poor, became a problem. Until then, old people were cared for by their families, or taken into the home of a friend. Poor people who ended up in the City’s Poor House were not differentiated from the mentally ill or dissolute people who were unable to care for themselves. One of the West Side’s historic organizations, the Association for the Relief of Respectable Aged Indigent Females, was formed in 1814 to deal with the problem of poor elderly women. The history of their Home at 891 Amsterdam Avenue has been covered in an earlier post but will be described here again, with new information recovered from a trove of their Annual reports discovered at the New York Public Library. Five other homes were in close proximity, starting in the late 19th century and into the early days of the 20th century, some lasting until the 1970s when everything changed with new Federal programs. This three-part article covers the history of caring for the aged in our neighborhood at these institutions and two others from more modern times, covered in Part 3. The Methodist Episcopal Home for the Aged at 673 Amsterdam Avenue, between West 92nd and West 93rd Street The Home for Aged Hebrews, originally located at 121 West 105th Street The Old Age Home operated by the Little Sisters of the Poor, at 135 West 106th Street Across 110th Street in the Morningside Heights neighborhood, The Home for Old Men and Aged Couples at 1060 Amsterdam Avenue at 112th Street The St. Luke’s Home for Aged Women at 2914 Broadway at 114th Street Civil engineer Egbert L. Viele wrote about the area: There is no dampness here on the west side. There is a dry tonic atmosphere which is not felt elsewhere in the city. It is more healthy than elsewhere. Elderly people like it here much better and with excellent reason. Introduction While the Association for the Relief of Respectable Aged Indigent Females got an early start in 1814, as the nineteenth century progressed other organizations formed to care for the elderly, at first for old women, and later for men. Older women were expected to be in need of support, but it took a while longer for men to be viewed in the same way. While numerous homes were operated by religious organizations, there were others established by mutual aid societies of workers’ organizations, or by certain immigrant groups. Today, for instance, we still have the buildings of Sailors Snug Harbor where “aged, decrepit and worn out” sailors were cared for, starting in the 1830s. Over time, the religious organizations, particularly Protestants, defined those who deserved their support, extending it to those who were poor because of illness or loss of fortune in contrast to those who could not take care of themselves or their families, perhaps through alcoholism. Even as they became adept at managing an asylum, groups turned away those who were mentally ill, leaving them to go to public institutions. In general, they wanted fairly healthy individuals, although they had infirmaries for those who became ill as they neared death. Four of the six home discussed here came about as a result of the efforts of women. The two north of 110th Street, in the Morningside Heights neighborhood, were connected to the Episcopal Church, and founded by one of its pastors, Reverend Isaac Tuttle, but had committees of women who were integral to the operation. Women who engaged in charity work in the nineteenth century became adept working outside the home, extending their social influence, and learning organizational and financial management. These skills carried over to the abolitionist movement, the temperance movement, and eventually the suffrage movement. The rules governing the position of Matron for both the Association for the Relief of Respectable Aged Indigent Females and the Methodist Episcopal Home for the Aged are remarkably similar, as if the two institutions were in close contact. The Matrons were charged with being respectful and kind to everyone, keeping the home in neat order, and enforcing the rules. The lights were to be extinguished by 10 pm, with others left burning throughout the night only as needed. No “spiritous” liquors were allowed unless a physician had ordered them, and then the Matron had to keep the supply and administer it. She was responsible for the preparation of meals, for the quality of the food, the timing of the meals, and that the prayer of grace was said at each meal. The women managers of the Home performed many duties that would later be handled by staff: ordering supplies, visiting each resident regularly in committees of two, visiting those they supported outside the home, and delivering clothing, food, cash and sometimes fuel. Three of the homes in Bloomingdale were designed by the firm D. & J. Jardine. David and John Jardine had immigrated from Scotland and formed one of the prominent firms in the city. They designed the asylums built by the Little Sisters of the Poor, the Methodists, and the B’Nai Jeshurun Ladies Benevolent Society. Landmark West Jardine buildings still standing in the West 80s. Research underway by one of the members of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group has identified 910 Amsterdam Avenue, 200 to 208 West 105th Street, and 202 West 108th Street as D. & J. Jardine buildings, all still standing. As time went on, and the population of elderly citizens increased, facilities changed. When Social Security began in the 1930s, there was a general increase in care homes in the U.S. and the “poor house” came to an end since those committed there could not receive Social Security payments. During the Depression, many people opened up their own homes to old people since they brought some income, although we have no particular knowledge of this activity on the Upper West Side. Finally, after World War II and beyond, when Medicare and Medicaid began, nursing homes became a business, and had significant impact on our neighborhood. The Methodist Episcopal Home for the Aged Just like the women of the Association for the Relief of Respectable Aged Indigent Females, and those of the Home for Aged Hebrews, the women of the Methodist Churches in New York City followed a similar path. They wanted to do something about caring for elderly women who faced the almshouse. In 1850, a group formed the Ladies Union Aid Society and, very quickly, a home was rented at 16 Horatio Street for 30 women. By 1857 space was tight, and they had raised enough funds to combine a two-lot gift of land with one lot purchased on West 42nd Street near Eighth Avenue. Here they built a 4-story building that housed 75 people, men included. The residents, referred to as “the Family,” had to belong to one of the many Methodist churches in Manhattan and apply through their own church. Every church had a committee to consider applicants. They did not accept anyone who was “insane or weak minded.” The Methodists had the usual “subscriptions” (annual donors) and those who left bequests to their Home. They accepted donations of food, clothing and furnishings, all scrupulously noted in their annual reports. They also offered two Benefits each year, celebratory events, such as an “Autumn Harvest Home Festival” that attracted church members from around the city, with special teas, and items for sale. The women in the Home always made some of the knitted and crocheted items, giving them useful work, and also helping the Home. In 1884 they bought eight lots on Amsterdam Avenue, on the block between West 92 and 93 Streets, and by October 1886 the residents were moving into their new home. One of the physicians said, “Its very location is suggestive of health, being on high and rocky ground, and in one of the non-malarious portions of the island. The Outlook is grand with a commanding view of the Hudson River and the Palisades.” Just inside the front door of the brick home was a chapel that could seat 400, and on the first floor there was a dining room, the Board’s committee rooms, parlors, the physician’s office, and offices for the matron and the housekeeper, along with ten bedrooms. The basement held the kitchen, laundry and drying rooms, the engine and boiler room, various closets and pantries, and a smoking room for the men.

Up on the second floor, the group’s Young Ladies Reading Association had a reading room with volunteers ready to read to those who could no longer read for themselves. The young ladies were also responsible for the Christmas celebration at the Home where each member of the Family was sure to get a gift. On the fourth floor was an Infirmary, and a small dining room for those who could not descend the stairs. All together there were 120 sleeping rooms, all with sunshine and fresh air as they faced outward on the streets or over the interior courtyard. Anyone who could do so was expected to assist in the work of the Home. Several physicians donated their services, and various Methodist ministers came to preach on Sunday afternoons. There were prayers every morning and evening. Board members served on various committees, performing tasks that today would be handled by hired staff. The Visiting Committee, in two-person teams, was charged with coming into the Home three times a week, one of them at a mealtime, and getting to know the residents and hearing their stories. Residents were not required to pay a fee to enter the Home, but they did have to turn over all of their property to the Home. Visitors were allowed only on Tuesdays and Thursdays. The Home had cemetery plots at Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn and Maple Grove Cemetery in Queens. News reporting on homes for the aged tended to focus on the members of the Board, gifts and bequests they received, and their building and expansion projects. Any comments about the residents were usually focused on how happy they are, and the home’s lovely atmosphere and comforts. In a 1906 news report, the Home’s annual “Christmas Market,” just after Thanksgiving, was held at the Home. The reporter focused on a blind woman, Jane Bennett, who, despite her lack of sight was able to make two pretty napkin rings with beads strung on wire and a pincushion shaped like a wheelbarrow. Another woman, age 97, who had been at the Home and the earlier one for 48 years, enjoyed the event, dressed in her “pink shawl and white tulle cap with ruchings and rosettes.” An old man, a “seadog,” in a sealskin visored cap and Uncle Sam chin whiskers” was helping collect payments for the items, and chatted about his days as “a mate or second-mate on ships from ’56 to ’60.” The Methodist Home has two written histories, one from its founding to 1892 and the other from 1850 to 1950. The second report gave a few details about the effort to relocate the Home in Riverdale. In the 1920s, the Methodists conducted a fundraising campaign, and, at the end in 1927, concluded that their Amsterdam Avenue property was worth more to them if they sold it and built a new home. The members of the “Family” were not happy with the plan to relocate much further uptown. One resident lamented that she would no longer be able to “go the Five and Ten, or walk down the Avenues to look in the shop windows.” But the plans went forward, and the new home was occupied in September, 1929. The history book provides the details of moving the elderly residents, getting them to part with years of accumulations and to leave their rooms with the walls covered with “pasted illustrations.” Each resident had a strong-minded volunteer assigned so that excess clothing could be tossed out, although one elderly woman insisted on bringing her heavy tailor’s iron, although she did agree to leave behind her corset covers. The plan to sell the Amsterdam Avenue property was thwarted by the Depression, so the property was instead leased for twenty years. One source says it was vacant until 1940 when it was taken down and two six-story apartment buildings were built. Sources used for this article and the two that follow are posted following Part 3, by Pam Tice, member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group Program Committee The Association for the Relief of Respectable Aged indigent Females Since the 2013 post (linked in Part 1) on the history of the organization and its homes for elderly women, the Annual Reports from 1814 to 1924 for the Association were discovered at the New York Public Library. This historical review includes several insights discovered in those reports.

The women who founded the Association were profoundly religious in their mission but were not from any particular Protestant church. In their first Annual Report their purpose is stated “God in his religious providence has reduced many respectable aged females to want. We feel it is our duty and esteem it a privilege to administer to them in comfort.” The women were the wives of merchants of the City, comfortable in their own lives. Nearly all of them were married and typically held positions on the Board. Many served for a lengthy time. In their first three years, the Board met at the Brick Presbyterian Church on Beekman Street, and then moved to private homes until they built their first Home on 20th Street, between Second and Third Avenues, after which all meetings were held there. Until the Home opened, the women collected funds and dispersed them to worthy recipients. A Visiting Committee was charged with using “the utmost endeavor to ascertain the real character of every person they visited, closely questioning them and inquiring the surrounding neighbors.” By 1818, they were concerned that “a great number of aged poor are constantly immigrating from Europe” and made a rule that, to receive their help, someone must be a resident of New York City for three years. By the early 1830s, the Association began a process to build an Asylum. The minister of the Church of the Ascension, then on Canal Street, preached a supportive sermon one Sunday, resulting in Mrs. Peter Stuyvesant convincing her husband to donate land on 20th Street. John Jacob Astor donated $5,000 provided the women could raise the remaining $20,000. And they did! These two leading New York City citizens gave the Association a social boost, and the Board became one that socially-connected women would spend their time. When the Home was opened on 20th Street, daily prayer and Sunday services were an integral part of the operation. The students at the nearby Episcopal Seminary helped staff the Chapel. The Home was expanded in the 1840s, and William B. Astor contributed another $3,000. They bought land in Yorkville in the 1850s to move uptown and build a larger home, but the Civil War, followed by the 1870s recession, held back their expansion. By the time the Association bought their land in Bloomingdale, Mrs. Edward Morgan was the “First Directress.” As the wife of ex-Senator and ex-Governor Edward Morgan, she also had the social aspects of her husband’s public life to handle. In 1877 the Morgans hosted a party at their Fifth Avenue mansion for President Rutherford Hayes. Engaging the well-established American architect Richard Morris Hunt to design their new home on Amsterdam Avenue at 104th Street gave the Association’s project the feature that has kept the building standing today. Hunt had designed an earlier version of the Asylum, when the Board thought they would be building on Fourth (Park) Avenue, but later found that the trains would be too close. When it was time to design the building for Amsterdam Avenue, Hunt may have simply dusted off his earlier plans. He was also busy then with the design of the base of the Statue of Liberty and William K. Vanderbilt’s home on Fifth Avenue. A “Committee of Gentlemen,” Headed by Edward Morgan, helped the women with their real estate dealings. The Association’s 69th Report in 1881 has a description of the features of the Home, as designed by Hunt. The original building was in a squared “C” shape with an interior courtyard, starting at the 104th Street corner, and fronting in Amsterdam Avenue, then Tenth Avenue. (In 1907 an extension was added by Charles Rich that extended the building to 103rd Street.) Starting at the bottom, the cellar extended under the entire building, and further extended under a portion of the sidewalk on Amsterdam Avenue. The Matron’s Room had “center speaking tubes and bells reaching to different stories and to the kitchens and laundry.” There were two large staircases and a “commodious elevator near the north staircase.” The basement had the kitchen, pantries, a laundry room, a drying room, and a linen room along with “Servants’ apartments.” There were bedrooms—doubles and singles—on every floor, linen rooms and shared bathrooms on all floors. The Board had their meeting rooms on the first floor, along with a parlor that may have served as a visitor’s room, and there was a “bright, airy chapel.” |