|

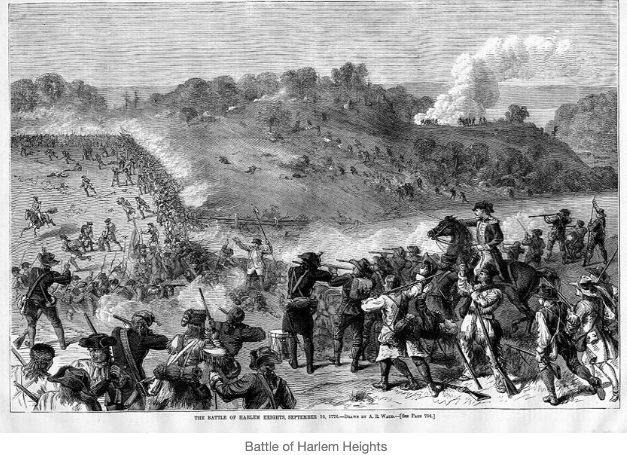

This is the third post about 18th Century Bloomingdale, written by Pam Tice, member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group Planning Committee. So many historians have written about the Battle of Harlem Heights on September 16, 1776, that I do not need to re-tell the story here. Jim Mackin presented a program about the Battle, centered around the Jones and Hooglandt farms, one evening back in 2019, and then wrote a post about here. There’s a much more detailed description of the Battle here: http://www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/battle-of-harlem-heights/ I’m focusing here on observations about Bloomingdale leading up to the Battle, and the seven years following, when the British had taken over New York City and imposed military rule. First, though, a detail about the battle I had not found before. The Striker house at West 96th Street became a sort of “field hospital” for the wounded of both sides during the Battle, as described by Hopper Striker Mott in an article he wrote for the publication known as the New York Genealogical and Biographical Record in July, 1908.

James Striker and his mother cared for the British and American soldiers that day, using his family wagon to convey the men from the battlefield to their home. Mott writes that a patriot and two Tories were killed in the lane which led from the Bloomingdale Road to the house, and they were buried near where they fell. British officers were quartered at the house and, Mott claims, one party of captives were billeted there, pending their removal to the improvised prisons at the lower end of Manhattan. James Striker eventually signed up with the American troops and fought in battles in New Jersey. While he was away, his house was pillaged twice during the British occupation and all the livestock lost. In 1781, he writes, “the slaves and servant men were driven off and the women compelled for days to cook and attend the wants of their captors.” At the time of the Battle of Harlem Heights, the British had sent three ships “to Bloomingdale on the North River,” the name of the Hudson often used at that time. The Phoenix and the Roebuck were 44-gun ships, and another ship, a frigate, had 20 guns. They were there to prevent the Americans from removing any provisions from the city. This Bloomingdale naval expedition also figured in the reports of American Sgt. Ezra Lee, who twice attempted to attack enemy ships using a “submarine machine” known as Turtle, in an attempt to blow up the enemy’s ships. He was not successful, but his efforts are noted by military historians as a first to use this type of warfare. Humphrey Jones also lost the use of his home in Bloomingdale during this time. After the war his son, Nicholas, submitted a memorandum of “sundry seizures and damages” done to his home by the British and Hessian troops, as they occupied his farm from September 17, 1776 to June 20, 1783. I have not seen the memo itself; copies of it were donated to the New York Public Library in 1921. Nicholas Jones’ papers are also archived at the New-York Historical Society. Merchant New Yorkers worked harder and longer to try to come to an equitable settlement with Parliament. The property owners of Bloomingdale were a mix of Tories and Patriots. Charles Apthorp made his money provisioning the British military in North America. Robert Bayard was the agent for the East India company in New York City. The Delancey family were activists for the Crown in the years preceding the Revolution; Oliver Delancey, owner of “Little Bloomingdale,” was a Brigadier General in the British Army. Both Charles Apthorp and Oliver Delancey were serving on the Colonial Council in 1776. Having grown up in New England where the story of the years preceding the Revolutionary War played out differently, I was amused by the report of John Adams himself being enraged by the behavior of the New Yorkers who even in June 1776 had not mobilized behind the war effort. “What is the Reason that New York is still asleep or dead in Politicks and War? …Have they no sense, no feeling…no passion?” he fumed. New York was the last of the thirteen colonies to declare independence in 1776. The prominent de Peyster family was politically mixed, but they did not settle in Bloomingdale until after the war, when Nicholas and his brother James bought the Hooglandt and Vandewater property. Their father, William, was reported in Albany during the War, which implies that he was a Patriot. Frederick de Peyster, a cousin, fought for the British and left for Nova Scotia in 1783. But he soon returned and owned property in Bloomingdale, according to property maps. One of his heirs, also named Frederick, headed the New-York Historical Society in the late 19h Century and organized a huge celebration of the Battle of Harlem Heights on its 100th anniversary. Day’s Tavern, located north of Bloomingdale at about 123rd Street (between Ninth and Tenth Avenues), is mentioned in various reports around the time of the Revolution. John Adams stopped there when he came through New York on his way to the Continental Congress. It is also a part of the detailed descriptions of the Battle of Harlem Heights. It is mentioned again when, in 1783, Washington made his way back into the City. The northern quadrant of Central Park, north of today’s 97th Street Transverse, was a major gathering point for British and Hessian troops during the War. At times, there were more than 1,000 soldiers there whose presence must have had an impact on anyone still trying to farm in Bloomingdale. Recent archaeological studies pinpoint the Great Hill and the area around McGown’s Pass as principal areas where evidence of Revolutionary War activity can be found. There was one incident in Bloomingdale that is cited by many historians writing about the Revolutionary War in New York City. On November 26, 1777, a band of Patriots tied up on the Hudson shore in the early hours of the morning and burned and pillaged the Delancey house. The story of that raid has been told multiple times, but this report in the New York Mercury is particularly brutal. The raiding party …plundered his house of the most valuable furniture and money, set the house on fire before Mrs. Delancey, her two daughters, and two other young ladies could remove out if it, which was effected through the flames, in only their bed dresses, when they were most cruelly insulted, beat, and abused, and what money they had, taken from them; an infant Grandchild in a most barbarous manner thrown on the ground; at last, in their fright and distress, they were made prisoners, and two infant children consumed in the flames. Other reports have the women hiding in the Bloomingdale woods until morning when they made their way to the safety of the Apthorp house. No children were harmed, and Miss Delancey manages to hold her brother’s infant in her arms all night, which she spent hiding in a swamp. The British occupation of New York City lasted until November 1783, when George Washington returned to the City, marching down through McGown’s Pass in Central Park and taking charge. The British evacuated on November 25, 1783, a date that was celebrated for many years in the City. After the war, the Delanceys lost all of their New York property as the state of New York confiscated it. Oliver Delancey’s Bloomingdale estate was broken up, with Mr. McVicar and Mr. Livingston owning portions of it. For unknown reasons, the Apthorp property in Bloomingdale was left alone. Perhaps Mr. Apthorp’s daughter’s marriage to a member of the Congress played a role in that decision. When Martha Lamb wrote her history of New York, she describes Charles Apthorp as “a courtly gentleman of wealth” welcoming all of wealth and fashion to his elegant Bloomingdale home for his daughter’s wedding. New York lifted legal restraints against Loyalists in 1793, and some who had fled the City, like Frederick de Peyster, were able to return. In the early years of the 20th Century, the New York Historical Society published numerous articles in their Quarterly magazine by various members who dug up British military buttons, and other parts of uniforms of both British and Hessian troops that they found in the Bloomingdale neighborhood and points north. Sources Howe, Adrian “The Bayard Treason Trial: Dramatizing Anglo-Dutch Politics in Early Eighteenth Century New York City” The William and Mary Quarterly Volume 47, No 1, January 1990 Hunter Research Inc., A Preliminary Historical and Archaeological Assessment of Central Park to the North of the 97th Street Transverse Volume 1. Central Park Conservancy and The City of New York 1990 Lamb, Martha History of the City of New York, Volume II New York, The A.S. Barnes Company, 1880 McKito, Valerie H. From Loyalists to Loyal Citizens: the DePeyster Family of New York Albany, State University of New York Press, 2015 The Nicholas Jones memo is included in the New York Public Library’s 1921 Annual Report on “items purchased” Mott, Hopper Striker The New York of Yesterday: Bloomingdale New York, The Knickerbocker Press 1908 Mott, Hopper Striker “Major General Garret Hopper Striker” The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record Volume XXXIX, Number 3, July 1908 “The Old Country Seats of New York Island” American Journal of Numismatics Volume 2 Number 11, March 1868 Stokes, I. N. Phelps The Iconography of Manhattan Island Volume 5 New York, Robert H. Dodge, 1928.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |