|

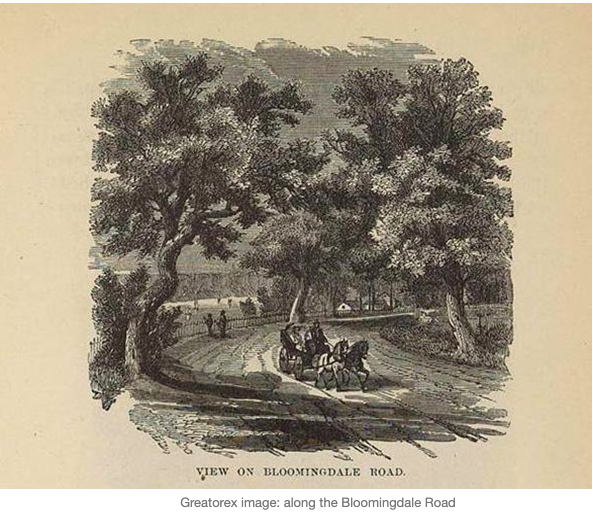

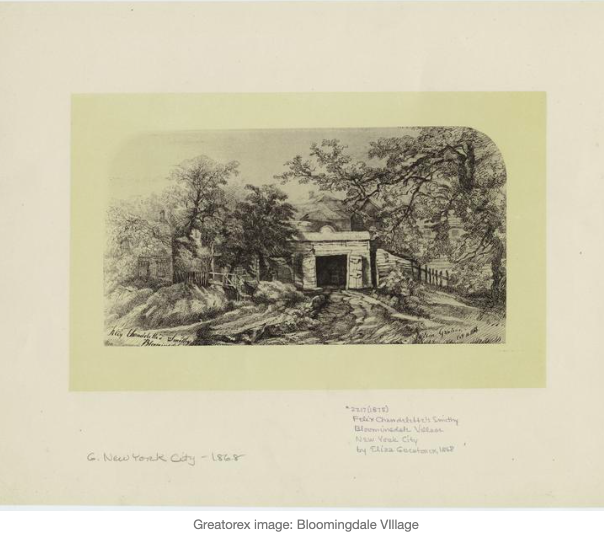

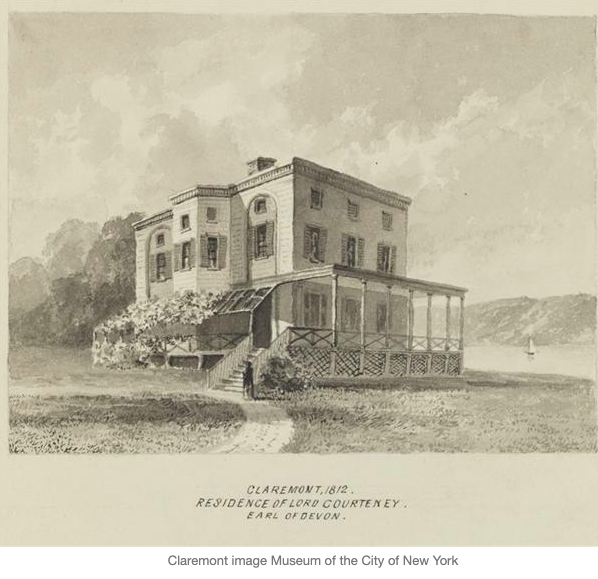

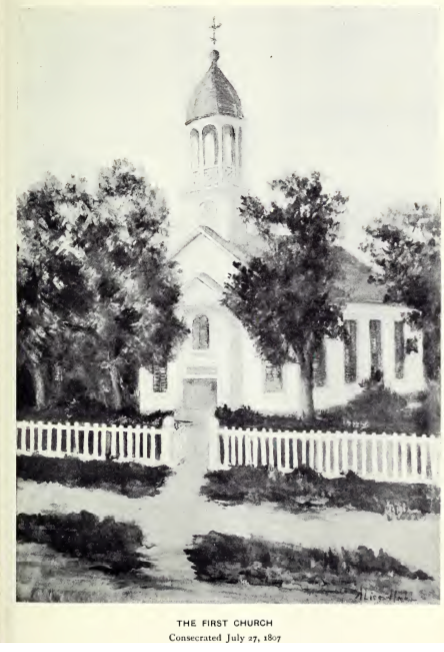

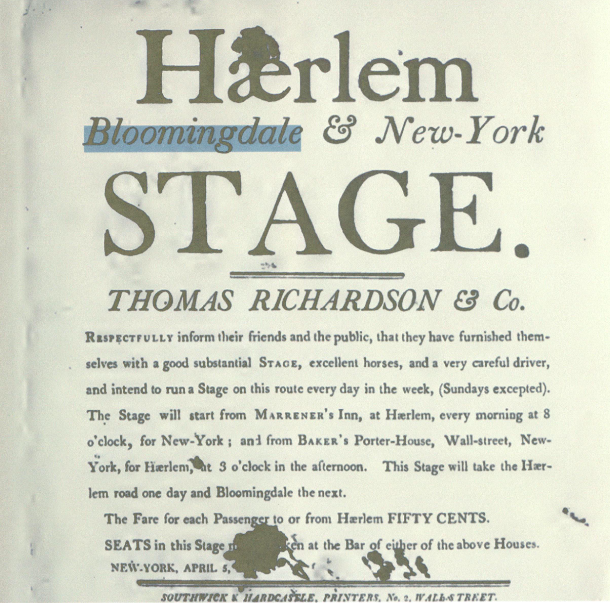

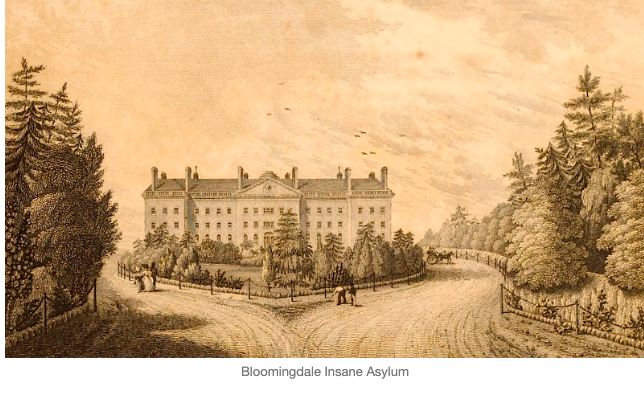

This is the fifth post on colonial and post-Revolution Bloomingdale written by Pam Tice, member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group. New York City had to recover from the Revolutionary War after George Washington marched back to downtown Manhattan in November1783. The city became the United States Capital until 1790, when it moved to Philadelphia. Population growth was strong from 1790 to 1820 when Manhattan’s population grew from 33,131 to 123,706, and doubled again by 1830. Bloomingdale grew and changed during this time also. The first census in 1790 shows the property owners: the de Peyster brothers, near where Columbia University is now, the Striker family at 96th Street, Charles Apthorp in the West 90s, the Harsens, Somerindykes and Cozine further south. Moses Oakley and Benjamin Stout, both designated slave owners, are also in the early censuses. My research shows them to be tavern owners, which I’ll cover in a separate essay. The large estates of the Bloomingdale property owners may have had estate managers or workers who were not enslaved, since there are other names listed in the early censuses. These people must have led quiet lives, as there are no newspaper articles or other records that would allow the researcher to identify them. Many historians cite the continuing epidemics of yellow fever between 1793 and 1805 as one of the reasons Bloomingdale’s population grew. No doubt that is true. The frightening outbreaks in downtown Manhattan had a more measurable impact on the development of Greenwich Village. Numerous banks, newspapers, and other businesses moved there along with the post office and the customs office. If a family had the means to do so, leaving the city for the countryside was necessary to avoid what the newspapers often called “the prevailing fever.” Yellow fever developed in many east coast cities, starting in the West Indies, and moving north on ships. New York began to develop its public health response during the 1790s and the first decade of the 19th century; funds were allocated to help families. The Common Council purchased Brockholst Livingston’s 4-acre estate known as Belle Vue, and a hospital to quarantine victims was developed there. Mr. Livingston had an estate in Bloomingdale too, named “Oak Villa,” in the West 90s near Mr. McVickar. By 1800 there are numerous others settled in Bloomingdale. Many slave owners were also property owners. We can identify Robert Kemble, who purchased the Jones estate in 1798. Two additional de Peysters, George and James, joined Nicholas. James was his brother and George was his son. Later, in 1810, Gerard de Peyster, son of James, would be listed. Nicholas’ very large estate, formerly the Adrian Hoaglandt land, was sold off over time to other owners. In 1796 he sold the portion known as Strawberry Hill to George Pollock, an Irish linen merchant, beginning the development of the estate known as Claremont. In 1805 Nicholas de Peyster sold his land to the south to Gordon Mumford, who had served as Benjamin Franklin’s private secretary when Franklin was representing the U.S. in Paris. Mumford returned to New York and became a successful merchant, establishing his country seat in Bloomingdale. John McVicar who owned land in what had been the Delancey estate prior to the Revolution, around West 84th Street, was described as one of New York’s “merchant princes.” Mr. McVickar is remembered for his generosity in offering hospitality to the rector of the new St. Michael’s Church during one of the summer yellow fever epidemics. His land also contained the popular small pond found on early maps where the Bloomingdalers skated in winter. John Clendening, the subject of an previous blog post, settled into Bloomingdale with his property further east, at 104th Street. By 1810, Mr. Jauncey had purchased the Apthorp property, and by 1811 William and Ann Rogers owned the Kemble property. Poor Mr. Kemble became bankrupt with one account of his troubles stating that he was left with only his watch as he settled his debts. Another Bloomingdale property owner, William Seton, also became “a bankrupt” in the late 18th Century. This fate was one of the fears of the merchants of New York, along with the yellow fever epidemics. Before there were laws governing the state of bankruptcy, one could be thrown into debtor’s prison. Mr. Seton died suddenly in 1798 and his son, William Magee Seton, struggled to maintain his father’s business. He sold property, including the 22 acres in Bloomingdale, advertised as between Robert Kemble and Nicholas de Peyster, in the early years of the 19th century. William Magee Seton’s wife was Elizabeth Bayley Seton, the first American to become a Saint in the Roman Catholic Church. Her religious conversion and struggle brought on by her family’s bankruptcy and illness sheds a light on the life of the New York merchants and the precarious nature of their businesses as they brought products into the New York market. Property sales in Bloomingdale reflect a trend of people purchasing smaller country estates. The larger estates of sixty acres or more were now broken into smaller ten and twenty acres or less with land available for cultivation. Very often an advertisement mentions the “respectable New Yorkers” who lived close by, as the de Peysters did in 1807 when advertising a house and land for sale, noting that Governor Clinton had spent the previous summer there. When the City’s first guide book was published in 1807, the area was important enough to mention in a description of the Bloomingdale Road where there were “numerous villas with which Bloomingdale is adorned.” During this time, Bloomingdale’s rural landscape became an attraction for those who owned horses and carriages, where an afternoon drive through the hills and valleys of the Bloomingdale Road brought great pleasure. Later in the 19th Century when circulating the carriage drives of the newly-built Central Park, writers would look back with nostalgia on the pleasures of driving through Bloomingdale. The taverns of the early 1800s, and “watering places” that became the Abbey, Burnham’s and Striker’s Bay hotels were all part of the enjoyment of the countryside so close to the city. Bloomingdale’s buildings and roads were the subject of numerous sketches made in 1875 by Eliza Pratt Greatorex in the folio volume she produced with her sister: Old New York: From the Battery to Bloomingdale. After the Civil War, many of these structures disappeared in the post-war building boom. Thanks to Greatorex, we have these images today. Mr. Pollock’s home just north of where Grant’s Tomb is located today is the site of a gravestone left there by the family and still part of our landscape now. His son, St. Clair Pollock, a five-year-old child, was killed there, perhaps playing on the Hudson’s rocky cliffs. The Pollock property exchanged hands numerous times between 1806 and 1821 when it became the home of the Post family and eventually part of Riverside Park. The house became the Claremont Inn, which finally disappeared in the early 1950s. Michael Hogan owned the house until his financial ruin caused by the War of 1812. One of the interesting characters Hogan leased the house to was Lord William Courtenay who had left England, and settled in Bloomingdale when his scandalous relationship with an art collector, exposed by his uncle, had forced him out of his own country. He was a mysterious neighbor, served only by one manservant and a cook. The New-York Historical Society has one of his letters in their files. Development on the west side of Manhattan was helped after the war by the extension of the Bloomingdale Road north of de Peyster’s home, until it met the Kingsbridge Road further uptown at 147th Street. After he purchased an estate north of Bloomingdale in 1806, Jacob Schieffelin developed a settlement called Manhattanville. Schieffelin had been a Royalist, a major figure in Detroit, who lived in Montreal after the Revolution for a few years. He then came to New York City to make his fortune in wholesale drug trading. He was active in St. Michael’s Church at 100th Street, and later founded St. Mary’s Church, also Episcopal, at today’s West 126th Street. The history of St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, built at 100th Street in 1807, mentions Bloomingdale residents who were the first vestrymen: Mr. Kemble, Mr. Rogers, and Mr. Jauncey. Oliver Hicks donated the land. Frederic de Peyster, a Loyalist cousin of the de Peysters already in Bloomingdale, returned from exile in Nova Scotia and established himself as a leading citizen of New York. His summer property was just south of 96th Street. He bought the church’s first bell. Mrs. Alexander Hamilton, whose estate was further north, bought a pew in the church. Another member was Valentine Nutter, whose property was east of Eighth Avenue, owned land that is now part of Central Park. His name exists today on “Nutter’s Battery” established during the War of 1812 in northern Central Park. The Bloomingdale Reformed Church was also established early in the 19th Century, further south near the Harsen property, at what is now approximately 69th Street and Broadway. Their first church was erected in 1806, replaced in 1816, again in 1869, and in 1885. Their final church, built in 1905, was in Bloomingdale Square, today’s Strauss Park. Another indication of Bloomingdale’s growth was the establishment of stagecoach service “to Apthorp’s” for 6 shillings. By 1806, however, the advertisement below shows a service where the coach alternated with the Harlem Road. By 1819, a regular line operated on the Bloomingdale Road, perhaps as a service to reach the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum, which opened in 1821 on land now part of Columbia University. Bloomingdale remained rural for much of the 19th century. In 1832 when an Englishwoman, Frances Trollope, published her generally caustic book “Domestic Manners of the Americans.” She was severely critical of the Americans whom she found to be both vulgar and prudish, as well as hypocritical in espousing freedom while keeping slaves. In New York, she stayed in Bloomingdale in the Woodlawn mansion, formerly one of the Jones’ family homes, where she found the mansion to be the loveliest in the village of Bloomingdale. The first institution to serve more than the local area was built in Bloomingdale in 1821: New York Hospital’s Bloomingdale Asylum for the Insane. A private hospital, its first building was where Columbia’s Low Library stands today. The Asylum’s 70 acres were described in an Evening Post article at the time of its opening in the spring of 1821 as “one of the most beautiful and healthy spots on New York Island.” The institution’s grounds included a large garden and orchards where patients could be healed by the work outdoors. Sources

http://blog.nyhistory.org/yellow-fever-hits-1790s-new-york/ Forstall, Richard L. Population of States and Counties of the U.S.: 1790-1990 Bureau of the Census, Washington, D.C. 1996 Newspaper articles at www.genealogybank.com and www.newspapers.com O’Donnell. Catherine Elizabeth Seton: American Saint Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 2018 Peters, John Punnett Annals of St. Michael’s Being the History of St. Michael’s Protestant Episcopal Church, New York, for One Hundred Years 1807-1907 , G. P. Putnam’s Sons New York and London, 1907 Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “New York City directory” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1790. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/dfc54ca0-e67b-0134-0aa0-5ddffb4c30ce Stokes, I. N. PhelpsThe Iconography of Manhattan Island Volume 5 New York, Robert H. Dodge, 1928 Washington, Eric K. Manhattanville, Old Heart of West Harlem Arcadia Publishing, South Carolina 2002.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |