|

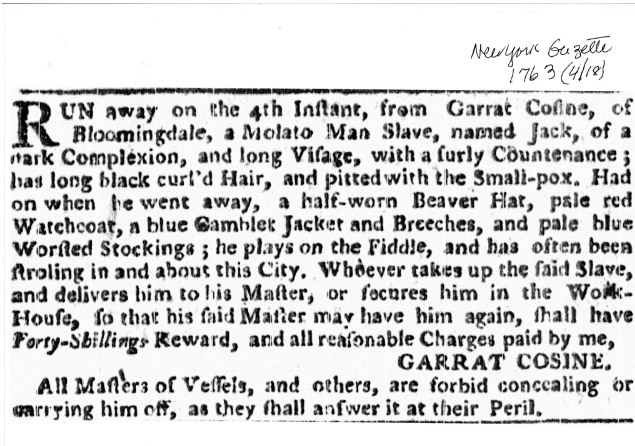

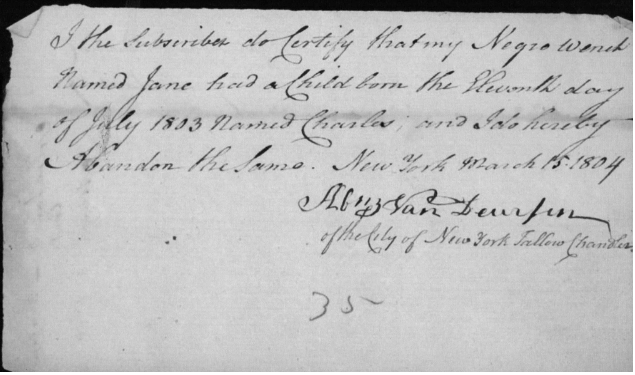

This is a fourth post on colonial and post-Revolution Bloomingdale written by Pam Tice, member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group. Now that I’ve written three posts about Bloomingdale in the 18th Century, I’m turning to the topic that caught my interest initially: slavery in Bloomingdale. As those who research family history know, finding details about African American ancestors is difficult. I had the same problem in trying to find factual information about slavery in Bloomingdale. Census information is available, and I’ll share what I found. Newspaper advertisements for runaway slaves or attempting to sell enslaved people are another source. Church records have some detail. I looked at all of these. I also looked for evidence of African American burial grounds. First, though, I had to understand the history of slavery as it played out in New York City. Scholars have explored the institution of slavery in New York City in recent years in great detail, producing a great number of books and articles. The discovery of the African American Burial Ground in lower Manhattan in the early 1990s encouraged many scholars to pursue the detailed research which has amplified the experience and historical identity of African Americans in our city. Of the books I read on this topic, I found Thelma Wills Foote’s book, listed below, of particular interest. The enslavement of African Americans was prevalent in colonial New York, where 40% of Europeans owned slaves, averaging 2.4 per household. By the 1720s, there were 5740 slaves in New York City, the greatest number of urban slaves outside the South. In 2015, the City recognized this part of its history by installing signage downtown at Wall and Water Streets to mark the 18th Century slave auction block. Under the Dutch West India Company, the first slaves arrived in 1626 and were put to work building the company’s infrastructure and working on the farms that grew the local food supply. Dutch merchants and artisans taught slaves how to handle their businesses, a practice that continued when the British took over the city in 1664. The Dutch extended some leniency: allowing some enslaved people to negotiate their freedom, and to own property. This image of Dutch New York pictures the enslaved people of that era. British merchants in New York were closely tied to the slave trade of the Royal African Company, and set out to make New York City the chief North American slave port. Early laws passed in the colony regulated the practice, and, by the early 1700s, freed slaves could no longer own property, and the hereditary nature of slavery was ensured by having children inherit their mother’s condition. Early laws made it very costly to manumit slaves. New Yorkers did not want untrained slaves coming directly from Africa. They preferred acculturated slaves whom they could train for various businesses such as tailoring, carpentry, or sail making. They began importing slaves from West Indian merchants, as payment for the provisions New York supplied them. New York’s enslaved people did not live in separate enclaves as they did on the southern plantations, but were given living space in the attics of larger homes or small outbuildings. They were often referred to as “servants.” In a 1780 advertisement in the New York Mercury for the Apthorp estate in Bloomingdale, the description includes “a two-story brick house “for an overseer and servants” in addition to the Manor House and other buildings. In the 1740s, in the time of what is called the Great Awakening, Quakers and Methodists began to call upon their members to free their slaves. Trinity Church began to baptize slaves, but would not admit them as church members. By the 1760s, the Dutch Reformed Church began baptizing slaves, after religious arguments settled the matter that baptism would not necessarily lead to freedom. These two churches were the first to build in the Bloomingdale area, although not until the early 1800s. African Americans In New York City During the British Rule, 1776-1783 There is a rich and complicated story about the British officials who offered freedom to the slaves of the American patriots. During the time of British rule in New York City, thousands of slaves fled to the City from all the North American colonies. They were given tasks related to both the war effort as well as keeping the City functioning. Many worked on clearing and rebuilding after the massive downtown fire of September, 1776. Other runaway slaves were absorbed into the Black Brigade of New York City, and housed in downtown barracks. One British officer of Bloomingdale, Brigadier General Oliver Delancey, was against using former slaves, but his opinion did not prevail. When the British evacuated the City in 1783, they issued “travel certificates” to black people who wanted to leave, thus giving a passport to freedom. In the Foote book cited below, she states that during the evacuation time April 23 to July 31, 1783, approximately 81 ships carried 3,000 black refugees away, most of them to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, where they founded free black communities. While most of these former slaves were from the southern states, 21 percent were from New York and New Jersey, and perhaps were former Bloomingdale residents. There is a document known as “the Negro’s Book,” that names those refugees, another opportunity to dig deeper into individual research on those enslaved in Bloomingdale. Many of the northern states ended slavery just after the Revolutionary War but New York did not, and continued to rely on slave labor. Even free blacks were close to slave status: they could not vote, nor be witnesses in a court of law, and they were taxed without representation. There were free African Americans in the Bloomingdale area, as noted in the comments on the federal censuses further on in this post. Before the first U.S. census in 1790, finding evidence of slave owners in Bloomingdale is anecdotal. A reference to Theunis Idens slaves is made by one historian. Some of the reports of the 1777 raid on the Delancey property in Bloomingdale mention slaves being driven off during that event; in his discussion of New Yorkers involved with the founding and management of King’s College, Eric Foner states that Oliver Delancey owned 23 slaves, and was a business partner of slave trader John Watts. Newspaper databases provide evidence of how enslaved people were described in colonial New York City. These newspaper advertisements cited here use the exact words that are in the ad or reproduce the ad itself; some may find them disturbing, but this is the reality of 18th century New York City. The word “wench” was used to refer to female Negro slaves. Here is a property sale in “Bloemendale” from 1758: TO BE SOLD … A Farm, situated at Bloemendale, near New York, containing about 100 acres, more or less; is in good Fence: There is on it a good Dwelling House, Barn and Orchard: — it is well timbered and watered, and has very good Meadows. There will also be sold at the same time, on the Premises, Horses, 19 Cows, Sheep, Hogs, & one Negro Wench, and a Negro lad about 20 years old; together with sundry farming Utensils, and household goods. New-York Gazette, November 13, 1758. Here is a April 18, 1763 newspaper advertisement from the New-York Gazette offering a reward for the return of a runaway slave: Another Bloomingdale neighbor, Garret Striker, offered this advertisement for the sale of one of his slaves in 1763: To be sold, being useless in the Family, a very likely well-set stout sober Negro Man, about 20 years of Age, is fit for Town or Country; with very little instruction he may readily be brought to wait on a Gentleman: He is Guinea born, can talk tolerable good English: Enquire of Garret Striker, Bloomingdale. The many long years of ending slavery in New York The New York Manumission Society was founded in 1785 by John Jay with the goal of gradually ending slavery in New York state by encouraging citizens to choose to manumit the people they enslaved. The Society was made up of influential white men; merchants, bankers, lawyers and judges. However, many of the Society’s members, including John Jay and Aaron Burr, kept their own slaves through the years of their involvement. Just last year, a paper was written about Alexander Hamilton’s role in the Manumission Society and his own participation in slave dealings both for his family and friends, known through entries in his personal cash book. The Federalists, as many of our Bloomingdale merchants were, favored a limited freedom for African Americans, guided and controlled by elites. After 1784 when a group of slave traders tried to seize a group of free blacks and sell them to the South illegally, New York state made this type of action illegal. New York State’s Gradual Emancipation Act of 1799 freed all children born to slave women after July 4, 1799, but indentured them to their mother’s masters until age 28, if male, and age 25, if female. If a slave master did not want to support and educate this child, he could turn him or her over to the City’s almshouse, where they would be indentured to a new master. While not from a Bloomingdale slave owner, this image is typical of this type of action: In 1817, New York State passed a law that freedom would be given to all slaves born before July 4, 1799, but not until July 4, 1827. Thus, in the early years of the 19th Century, slavery continued throughout the City and in Bloomingdale, where the census records reveal the practice from 1790 to 1820, as discussed below.

Census Counts of Enslaved People in Bloomingdale The 1790 federal census, the first in the new United States, counts the numbers of slaves owned by the people enumerated, after grouping males and females by age categories. Using the table for the “Harlem District” which contained the Bloomingdale area, I was able to narrow down the entries for known Bloomingdale families and counted their reported slaves. There are a total of 50 enslaved people, with Mr. Apthorp reporting eight, Nicholas de Peyster seven, the Somerindyke residents nine slaves among three families. The relatively high numbers perhaps imply that these were working farms. Of interest are a few lines in this census listing only the first name of a person, and giving a number in the column “all other free persons.” There is no notation among the Bloomingdale families, but under In the listing for Susanna Day, presumably of the Day’s Tavern mentioned in my previous post, there are two slaves listed. Under her name, “Cuff” and two free persons are listed. Cuff has no surname. “Cuff” was a popular slave name, reflecting the Akan-Asante society of Africa’s West Coast, where “Cuffee” meant “Friday.” There are several other such listings with only a first name, and a count of free persons, in the district. In the federal census for 1800, Bloomingdale is in Ward 7, and the names are arranged in some order with the de Peysters at the top of the page and the Harsen family further down, as if the census taker moved from north to south. There are 41 slaves counted. But certain Bloomingdale property owners were not counted here; John van den Heuval and John McVickar were counted downtown in Ward 4, where van den Heuval reported ten slaves and McVickar just one. Brockholst Livingston was also counted as a downtown resident; he owned four slaves in 1790 and one in 1800. When we get to the 1810 federal census, the names of Bloomingdale property owners are more scattered as if the census taker did not move through the district in one sweep. The de Peysters are listed close to Mr. Harsen, and the Clendening and Jauncey families on another page. However, there are still slave owners in Bloomingdale. The de Peysters have three slaves between them; Mr. Rogers has one person enslaved. Jauncey and Clendening have none. The Ward 9 census also included the east side of Manhattan where there are many more, perhaps a sign that there was more intense farming there. The 1820 census for Ward Nine shows the Bloomingdale families on several pages, not grouped together. This census is more complicated in its data collection. First there are 11 columns counting males and females in a household broken into age categories. Then there are 4 columns indicating non-naturalized foreign persons in the household, and three columns to check if the group engages in agriculture, commerce or manufacturing. This section is followed by 8 columns to count enslaved people, breaking down the count by age. Finally, there are 8 columns to indicate “Free Colored Persons” by several age groupings. Here, we can see the James Striker family with seven family members, a check that the family is engaged in agriculture, four slaves, and five Free Colored Persons. Nearby, Frederick de Peyster 15-person count of males and females indicated that commerce is the family business, with no slaves and three Free Colored Persons. The relatively few enslaved people in the 1820 census in Bloomingdale is representative of the overall city, where only 518 slaves are enumerated. A research project emerged from using the first four censuses: noting non-property-owning residents of Bloomingdale, and then attempting to discover who they were. This only proved successful if other records were found, particularly newspaper advertisements or stories, or vital records reproduced in various genealogical sources. This process uncovered two Bloomingdale tavern owners who owned slaves whom I’ll write about in a separate post. African American Burial Grounds I have uncovered no mention of a burial ground for Bloomingdale’s enslaved people. There may be a link to African Americans interred in the recently rediscovered African American Burial Ground connected to the Harlem Reformed Dutch Church at 121 Street on the east side. The historians working on that site have a website showing the results of their work over the past several years. There are details here: https://www.habgtaskforce.org/home. Records available through the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society show that the Church had members Gerard de Peyster and his family married and baptized there. If a Bloomingdale family was worshipping there, perhaps enslaved people were also, and could access the burial ground. .In the early years of the 20th Century a road-building project in northern Manhattan uncovered an African Burial Ground in Inwood. The discovery and history are detailed here: https://nycemetery.wordpress.com/2018/06/13/african-burial-ground-inwood/ This discovery made me wonder if Bloomingdale ever had such a burial site that may now be lying under an apartment building or street. In his history of St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, Reverend Peters states that large landowners often established private family burial places on their estate, and, one can imagine, a place for slave burials. The Church was not established until 1806, and its burial ground surrounding the church was reserved for members. There are records of the baptism of enslaved people, some referred to as “servants.” Anthony, son of Catherine, a black woman, servant of Mr. McVickar, was baptized in 1809; John and Jane, slaves of Mr. Davis, were baptized in 1816. In 1828, the Church established a cemetery on 103rd Street, to the east of Amsterdam Avenue near Clendening Lane, for “poor people,” but this happened after slavery had ended. This research process is fairly dynamic and new information is sure to be discovered, but my work will end here for now. Sources African American Burial Ground site: https://www.habgtaskforce.org/home Ancestry’s census information at www.ancestry.com Burrows, Edwin G., Mike Wallace, et al Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 New York, Oxford University Press 1999 Columbia University’s site exploring slavery and the University; in particular, Eric Foner’s paper: https://columbiaandslavery.columbia.edu/content/eric-foners-report Foote, Thelma Wills Black and White Manhattan: The History of Racial Formation in Colonial New York City New York, Oxford University Press, 2004 (Accessed online through the New York Public Library September 6, 2020) Goodfriend, Joyce D. “Slavery in Colonial New York City” Urban History, Volume 35, Number 3 (December 2008) pp. 485-496oodfriend, Joyce D. “Burghers and Blacks” The Evolution of A Slave Society at New Amsterdam” New York History Volume 59, Number 2 (April 1978) pp. 125-144 Harris, Leslie M. In The Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City 1626-1863 Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 200 John Jay College Slave Records Index online at https://nyslavery.commons.gc.cuny.edu/ Newspaper databases at www.genealogybank.com and www.newspapers.com New York Genealogical and Biological Society at www.nygbs.org. I used the Record for October 1986 Vol 117, issue 4 to find Harlem’s Reformed Dutch Church, and a 1902 article in Volume 13, reprinted in 1968. Peters, John Punnett Annals of St. Michael’s, Being The History of St. Michael’s Protestant Episcopal Church, New York for One Hundred Years 1807-1907 New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1907 Salwen, Peter Upper Westside Story New York, Abbeville Press, 1989 Serfilippi, Jessie “As Odious and Immoral A Thing: Alexander Hamilton’s Hidden History as an Enslaver” Schuler Mansion Historic Site, Albany, New York, 2020 Stokes, I. N. Phelps The Iconography of Manhattan Island (all volumes) New York, Robert H. Dodge, 1928.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |