|

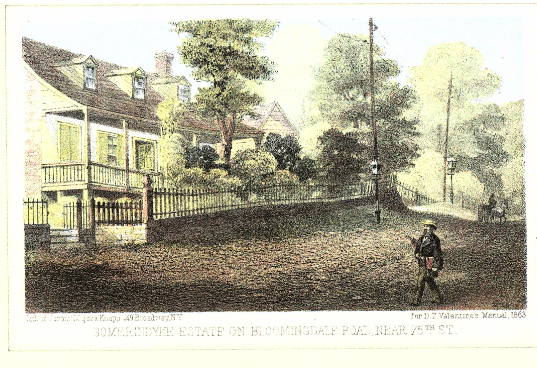

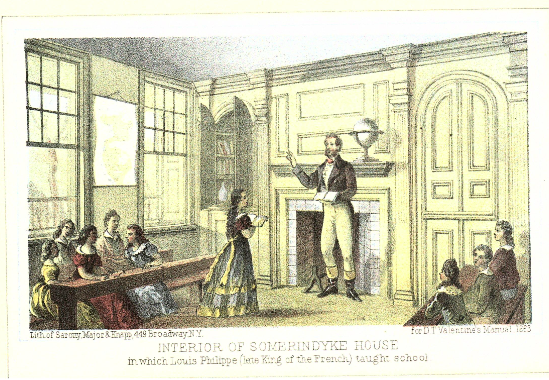

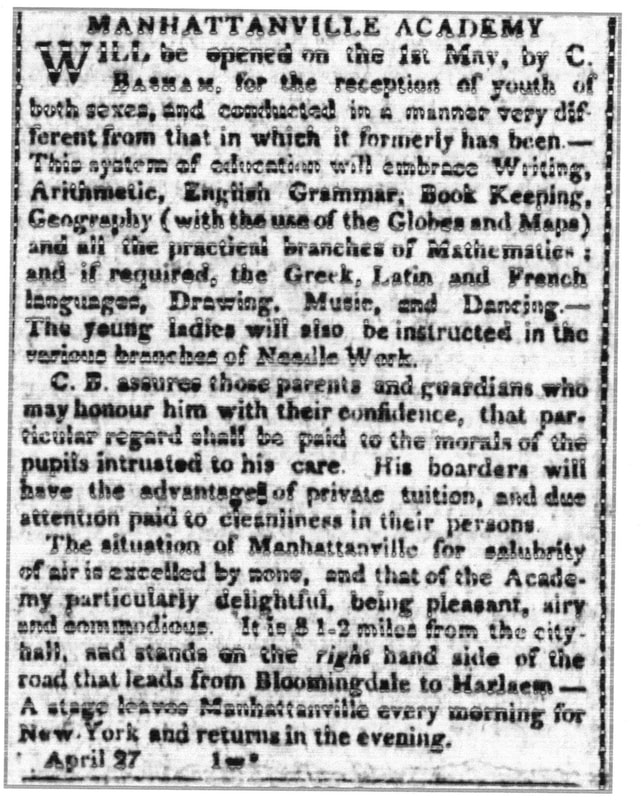

This is the seventh and last in this series exploring colonial and post-Revolution Bloomingdale written by Pam Tice, Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group Planning Committee member. As parents cope with educating their children in this complicated time, it’s been interesting to look back to the late 18th and early 19th centuries when schooling was handled quite differently. It was not until 1842 that the Board of Education was formed, bringing the schools closer to what we have today. This post looks at how children were educated before the emergence of a “school system.” When New Amsterdam was founded, schooling children was the responsibility of the Dutch Reformed Church. When the British took over the colony in 1664, they kept the same practice, keeping the Dutch Reformed Church schools and adding the Church of England’s Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts to oversee education. In 1709, Trinity School, a Bloomingdale School of today, was founded by Trinity Church, the Anglican church in downtown Manhattan. After the War of Independence, the New York Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves established the African Free School for the children of slaves and former slaves; by 1827, that system had grown to seven schools. The Free School Society was established in 1805, modeled on the African Free School. Later, it became the Public School Society. These schools were for poor white children of any religious background whose family was unable to afford private, paid education. These free schools, along with the religious-oriented charity schools, received public funding in 1795 and continuing for a number of years. The stated ideal of the separation of church and state took a while to catch on in the early years of United States. First, public funding of church charity schools was withdrawn. Eventually, by the mid-19th Century, legislation specifically prohibited denominational religious instruction in public school classrooms. It is against this background that educating children in the early years of Bloomingdale can be discovered. The wealthy merchants who established their “country seats” here no doubt had private tutors for their children who taught them in their own homes. The school masters who taught Bloomingdale children had to advertise their services, as reflected in 1794 when Asa Borden took an ad in the Daily Advertiser newspaper announcing that he was continuing as usual in Bloomingdale teaching literature, writing, arithmetic, book-keeping, English grammar, while “paying strict attention to the morals of his pupils.” He promoted the “salubrious situation of the place” that education would be better in the countryside where there were no vices to distract his pupils. He mentions Moses Oakley and James Striker among those who could recommend his services, and offers “genteel boarding” near the school —- although the location is not specific. One of the often-told stories about the West Side is about a tutor—King Louis Philippe of France. When he was a young man, long before he became King in 1830, he had to leave France during the Reign of Terror (1793-94) and supported himself by teaching. King Louis Philippe taught at the Somerindyke residence where Broadway and 75th Street are today. His sojourn in our neighborhood is commemorated in this print from an 1860s Valentine’s Manual. In Stokes’s Iconography of Manhattan Island, Volume 5, there is a reference to a school in Bloomingdale in 1797. James Striker and others referred to as the “trustees of School 30 in Bloomingdale,” petitioned the Common Council for funding to meet the gap between those who were paid subscribers and “parents who are unable to pay tuition.” Their problem was the gap between those who supported the school in summer but “removed to Town in winter,” leaving the less-wealthy parents who lived in the area year-round to cover the costs. In 1805, another advertisement refers to an “Academy” established in Bloomingdale. In 1804, a Mrs. Martin advertised a school in Bloomingdale for the summer season between the five- and six-mile stone, near Alderman Harsen’s. This school was one for young ladies as boarders or day-scholars. In 1811, two advertisements refer to “Mr. Derry’s” school at the six-mile stone with boarding available for boys at the parsonage of the Bloomingdale Reformed Church. As the village of Manhattanville developed starting in the 1800s. It was a project of a returning Loyalist, Jacob Schieffelin, who purchased property there. In 1806, he established the Manhattanville Academy and often cited it in real estate advertisements. This 1809 advertisement for the Academy gives the details of the education a child might receive there: St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, built in 1807 on 10th Avenue near 100th Street as a “summer chapel,” established a “charity school” in 1815. This school received public funding until 1824, when it was withdrawn but the school struggled to continue, with the son of the Rector teaching for free. In 1824, there were 48 children in the school—22 boys and 26 girls—showing the number of children in the Bloomingdale neighborhood who were not able to attend a fee-based school.

In 1826, a committee was appointed to report on the expediency of establishing schools in the 12th Ward which included the Bloomingdale neighborhood; James De Peyster served on it. The St. Michael’s charity school was soon adopted by the Public School Society, and the local committee searched for funding to build a school. They purchased a building lot on 82nd Street between 10th and 11th avenues but did not actually erect a building until 1830. This school became Public School Number 9 in the City’s emerging public school system. In an 1843 report on the city’s schools, all the schools were described as three stories in height, with the exception of the small School 9 in Bloomingdale. In 1812, the Bloomingdale Union Academy, five miles from the city, was established. It was described as being under the inspection and direction of an Association of Gentlemen, a list that includes a number of property owners of Bloomingdale, including James Striker. The advertisement in 1814 mentions a large house next to the Academy, occupied by “Mr. John M’gregor, Sen., as a boarding house for the accommodation of scholars.” The fees of the Bloomingdale Union Academy are an interesting detail: For instruction in Reading, Writing, Arithmetic, Grammar, and Geography 28 dollars per annum and 3 dollars as entrance money—each quarter’s tuition is to be paid in advance. For instruction in the Latin and Greek languages and Mathematics, 40 dollars per annum and 5 dollars entrance. The children whose parents live at a distance can be accommodated with board in the house belonging to the Association at a sum not exceeding 500 a year, exclusive of washing, mending, beds and bedding. Washing and mending can be obtained at a cheap rate in the neighborhood. Also in 1812, an Ursuline Convent was announced near the six-mile stone on the Bloomingdale Road. This Catholic order was founded in 16th Century Italy, and dedicated to the education and spiritual development of young women. The advertisement for the Convent sought young ladies of all denominations, offering a “polite and virtuous education.” The subject list was long: English and French languages, reading, writing, arithmetic, geography and the use of globes, history, chronology, grammar, poetry, and every species of plain and variegated needlework, together with music, drawing, and dancing. The advertisement in the Mercantile Advertiser on September 12, 1812, sought only twelve students in the next three months. The effort to establish an Ursuline convent in Bloomingdale failed, however, attracting no postulants, and the Ursulines established themselves in the Bronx later in the 19th Century. In 1819, another Boarding School under the direction of Rev. William Powell was advertised five and a half miles from the City, adjoining the seat of William Jauncey. At that time, Mr. Jauncey was the owner of the old Apthorp mansion. Students would range in age from six to sixteen. An interesting description of discipline is in this advertisement: The discipline of the School will be mild and parental, yet sufficiently energetic to induce attention and habits of industry; and the refinements of polished life shall be recommended and encouraged by the most kind and liberal treatment. This essay ends my research on Bloomingdale in the early years of the 19th Century. Sources Stokes, I. N. PhelpsThe Iconography of Manhattan Island Volume 5 New York, Robert H. Dodge, 1928 New York City Public Library Blog post: https://www.nypl.org/blog/2014/10/20/researching-nyc-schools Peters, John Punnett Annals of St. Michael’s, Being The History of St. Michael’s Protestant Episcopal Church, New York for One Hundred Years 1807-1907 New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1907 Kaestle, Carl F. “Common Schools before the ‘Common School Revival’; New York Schooling in the 1790s” History of Education Quarterly Winter 1972, Volume 12, Number 4 pp. 465-500 Newspaper articles from www.genealogybank.com and www.newspapers.com. https:/nycemetery.wordpress.com/2020/10/09/ursuline-sisters-burial-grounds/

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |