|

This post was written by Pam Tice, a member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group Planning Committee The Home for Old Men and Aged Couples and St. Luke’s Home for Indigent Females

Both of these homes, developed by New York’s Protestant Episcopal Church, were in Morningside Heights, to the north of our Bloomingdale neighborhood. They were both founded by The Reverend Dr. Isaac Tuttle, Rector of St. Luke’s Church. He first established a home for women in 1852 at 543 Hudson Street, for “gentlewomen in reduced circumstance.” When larger space was needed in 1859, the women were moved to a house next to the church at 487 Hudson Street. The congregation of the church and their friends supplied all the needs of the home. By 1872, the home for women was relocated to Madison Avenue and 89th Street. Meanwhile, seeing the need for care developing for elderly men, Rev. Tuttle formed the Home for Aged Men and Aged Couples in the building at 487 Hudson Street. The men were “rescued from lonely want and suffering” and aged couples were “saved from the bitterness of separation.” When the Cathedral of St. John the Divine construction began in the 1890s, the Episcopal Church moved both homes to the Morningside Heights neighborhood. The Home for Old Men and Aged Couples was moved into a new five-story building at Amsterdam Avenue and 112th Street, on the northwest corner, across the street from the Cathedral. The land was purchased in 1897 and the home opened the following year. The St. Luke’s Home for Aged Women was built in 1899 at 2914 Broadway, at 114th Street. The Home for Old Men and Aged Couples had a “Board of Lady Associates” in addition to its regular Board. Both homes required admission payments: in 1921 the fee was $500 for the women at St. Luke’s, $400 for the men and $700 for a couple in the Home for Old Men and Aged Couples. Applicants had to be resident of the City for five years, 60 years or older, and a member of one of the City’s Episcopal Churches.

0 Comments

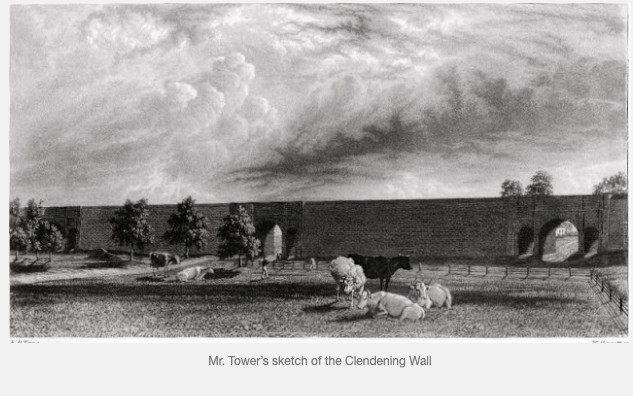

Once we had a wall running right through our Bloomingdale neighborhood. Only it wasn’t called a wall; it was the Clendening Bridge, a portion of the Croton Aqueduct, the city’s first major infrastructure project to address the problem of getting clean water to New York City. Thanks to a young engineer named Fayette Bartholomew Tower, we have this drawing of our Clendening Bridge, published in his 1843 book after the Croton Aqueduct was finished. Even though the Bridge remained in place until the 1870s, no photograph has been found (yet).

The Croton Aqueduct, including the Clendening Bridge, ran through our neighborhood about 100 feet west of Columbus Avenue. It came down Amsterdam Avenue and swung over at an angle toward Columbus Avenue, straightening out at 105-104 Streets to head downtown in a straight line. Of course these avenues were Tenth and Ninth then, and not the roadways they are today. Much of the entire Croton Aqueduct was an above-ground “horse-shoe shaped brick tunnel 8.5 feet high by 7.5 feet wide, set on a stone foundation and protected by an earthen cover and stone facing at the embankment walls” according to a description by the Friends of the Old Croton Aqueduct. Here is another post on the Bloomingdale neighborhood of the Upper West Side. It was written by Pam Tice, member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group’s Planning Committee.

Bloomingdale’s residential development brought numerous retail food shops into the neighborhood, from the late 1880s to today, when the latest food store opening can still create excitement (see the frequent reporting on the new Trader Joe’s!). This post began as a search into our neighborhood food stores, focusing primarily on 86th to 110th Streets. This is a bit of an evasive topic, since most stores were small family-run businesses that did not advertise, and nor were publicly photographed. Moreover, the stores were part of a larger food retailing history from which individual stores developed, and how certain common products were created. Restaurants are another significant part of the neighborhood food story which were covered in an earlier post. Food history is a popular topic among historians now. A recently-published book, Feeding Gotham: The Political Economy and Geography of Food in New York 1790-1860, by Gergeley Baics gives a fascinating history on how “food provisioning” developed in New York City. This book details the changes in the city’s food distribution as it changed from restricted public marketplaces built by city government to privatized food distribution as a function of the marketplace. These food markets were once part of the city’s landscape: Fly Market (replaced by Fulton), Catharine Street, Essex, Jefferson in Greenwich Village, and the Washington Market, on the lower west side. By the 1870s, the Gansevoort Farmer’s Market, near the Washington Market, was established: a vast stretch of wagons, as pictured below. Meat, poultry and dairy purveyors as well became the distribution center for the wholesale merchants who supplied the retail stores. This section of the city eventually gave way to Hunt’s Point in the 1960s, and what we now call Tribeca emerged as a new residential neighborhood. Here is another post on the Bloomingdale neighborhood of the Upper West Side. It was written by Pam Tice, member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group’s Planning Committee.

A previous post about food provisioning in Bloomingdale described the streetscape of Columbus, Amsterdam and Broadway, a dynamic jumble of food suppliers: fruit and vegetables, bakeries, meats, seafood, delicatessens, and wine/liquor stores. From 1890 to 1940 while a few food suppliers became chain stores, most Bloomingdale neighborhood shops remained “mom and pop” operations. This post highlights a few of the other non-food shopkeepers providing goods and services for the neighborhood. With few exceptions, these also tended to be small shops: bootblacks early in the century, tailors, barbers, women’s hair salons, pharmacies, upholsterers, milliners, corset and flower shops. In the early years of the 20th century, the Upper West Side had an “Automobile Row” just above Columbus Circle where General Motors, Ford, Buick, Cadillac, Studebaker and Packard had display spaces. However, further uptown the stores tended to be small operations, each serving the neighborhood’s needs. Early on, there were numerous neighborhood bootblacks. One of them was Riddick Darden, who is listed in the 1900 Trow Directory. The 1900 census reveals that he was a black man, living in a rooming house on 99th Street. He appears to have been a neighborhood regular, as he is still there in the 1920 census listed as the owner of a “bootstand” at 99th street. Caitlin Hawke in her research of Bloomingdale neighborhood stores found this photo of Broadway’s northeast corner at 103rd Street, showing a shop selling feed and grain, demonstrating the country-like atmosphere of the turn-of-the-century Bloomingdale. The odd-shaped building on the horizon is the Home for the Destitute Blind constructed in 1886 but removed about thirty years later. Summary of Presentation by Dr. William Seraile on February 27, 2018

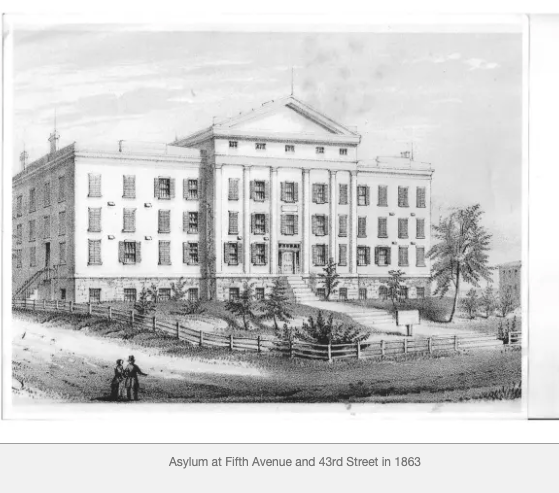

William Seraile is Professor Emeritus of History at Lehman College of the City University of New York. He is the author of five books, including “Angels of Mercy: White Women and the History of New York’s Colored Orphan Asylum.” The Colored Orphan Asylum (COA) was founded in 1836 by three Quaker women. It was sorely needed, since youth of color were excluded from orphanages for white children. The orphanage faced many obstacles throughout its existence including financial panics, fires, diseases and chronic money shortage. Racism led to its complete destruction in the Draft Riots of July 1863, when its building at 43rd and Fifth Avenue was looted and burned by the mob. The frightened children and staff escaped to the protection of a nearby police precinct and then to Blackwell’s Island (Roosevelt Island). This post covers another one of Bloomingdale’s lost structures. It was written by Pam Tice, a member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group’s Planning Committee.

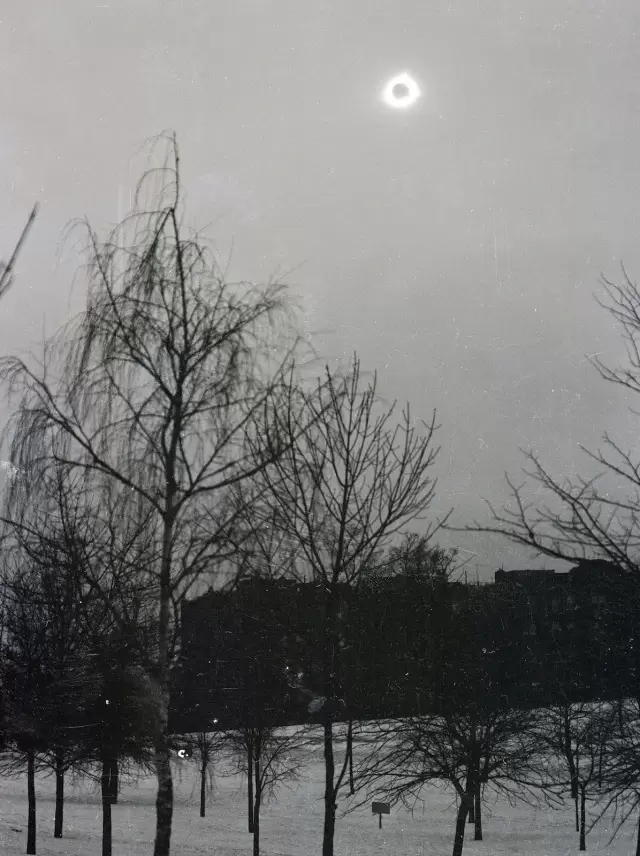

When you walk from West 96th to 91st Streets on Columbus Avenue, or walk east from Broadway to Columbus on those streets, you’ll notice you are on a hill. The crest of the hill on 91st Street, about 100 feet west of Columbus, is the location where, starting in 1764, a colonial mansion stood for 130 years. Originally, it was surrounded by a 300-acre estate. Over the years, though, the land was whittled back through legacy gifts and real estate sales, as the development of the West Side played out until finally, just the mansion stood, surrounded by a small park. This structure and the land encapsulates the history of our Bloomingdale neighborhood, and is presented here. In 1764, wealthy merchant Charles Ward Apthorp built what was widely recognized as one of the finest mansions in all of New York City. Like many of his contemporaries, Apthorp purchased land on the west side of Manhattan, no doubt picturing himself as one of the landed gentry of the American colony. He had moved to New York from Boston where his father, Charles Apthorp, was one of New England’s wealthiest merchants, and served as the paymaster and agent for the Royal Army and Navy, furnishing supplies and money to the British forces in Boston and Nova Scotia. He also imported and sold many kinds of goods, including slaves. His eighteen children married into many of the other prominent families of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Now in New York, Charles Ward Apthorp married Mary McEvers at Trinity Church in 1755. She was the daughter of John McEvers of Dublin, another successful New York merchant. They had ten children: Charles, James, George, Grizzel (named for her Boston grandmother), Eliza, Susan, Rebecca, Ann, Mary/Maria, and Charlotte; six of them lived to adulthood. written by Pam Tice, a member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group’s Planning Committee In this summer of 2017 as we prepare for the solar eclipse on August 21, a recent reference to the 1925 eclipse in The New York Times and the importance of our Bloomingdale neighborhood inspired further research. This event, known as the Upper Manhattan Eclipse, did not occur in the heat of summer, but on a freezing, cold day: January 24, 1925. Predictions of the path of a solar eclipse were pretty accurate by 1925, but not perfect. Ancient societies—including the Babylonians, the Chinese, and the Maya—had developed the ability to predict solar eclipse patterns, but it wasn’t until 1715 that astronomer Sir Edmond Halley made his critical breakthrough, using Isaac Newton’s law of gravity. This achievement enabled predictions of exactly where the eclipse would occur and how long it would last at that point. Astronomers had predicted that the total solar eclipse in January 1925 would travel across the U.S., and the edge of the “total darkness” would hit the west side of Manhattan around 72nd Street. Everyone north of this edge would experience total darkness, while those south of it would be in the “partial” area, just as all of New York City will be this year. However, as the 1925 eclipse proceeded, and reached totality at 9:11 AM, the edge turned out to be somewhere between West 96th and West 97th Streets. Scientists had learned something new and added to their knowledge base. Pundits named it “The West 96th Eclipse.” There was the usual preparation for this event in 1925 —- the news warned individuals to look at it through tinted glasses, a bit of exposed film, or even a broken piece of dark blue or brown glass. The greatest new efforts appear to have been the need to get up high in an airplane. News reports of the day reported that the 25 airplanes that took off from the Army Air Corps’ Mitchel Field on Long Island. Another exciting feature of the day was the U.S. Navy’s airship Los Angeles which they brought to Lakehurst, New Jersey, and flew out over Montauk on the morning of the event, loaded with cameras, telescopes, and 42 people. Here’s short film of that event: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l7XPjfCaltw Many spectators went up into the city’s skyscrapers, hoping to get a viewing post above ground. The Woolworth building opened their observation deck early. Although it was a Saturday, this was still a workday for many, and even the New York Stock Exchange was open, although with a delayed opening that day. Passengers on ocean liners in the harbor crowded the decks in the cold morning air. Uptown, students crowded onto the Columbia and City College campuses, and others headed for open spaces in Central and Riverside Parks, and further uptown in Washington Heights. Many people must have been ready to just stay in bed on this Saturday morning, since the temperature was at just nine degrees, and a record-breaking 27 inches of snow had blanketed the city days before. (That record wasn’t broken until the 2011 snowstorm.) Here is a photo owned by the Mystic Seaport Museum, Rosenfeld Collection; it’s identified as taken in New York City, and probably somewhere north of 96th Street. On January 30, 1925, the Jewish Chronicle of Newark printed a thoughtful piece: “The Eclipse From a Moral Point of View” marveling at the work of scientists to gain every possible bit of information from the memorable event, and urging people to respect the precise methods of the scientific spirit in a world where wild rumors, malicious gossip, and subtle propaganda can often replace durable truth—something to remember this year also!

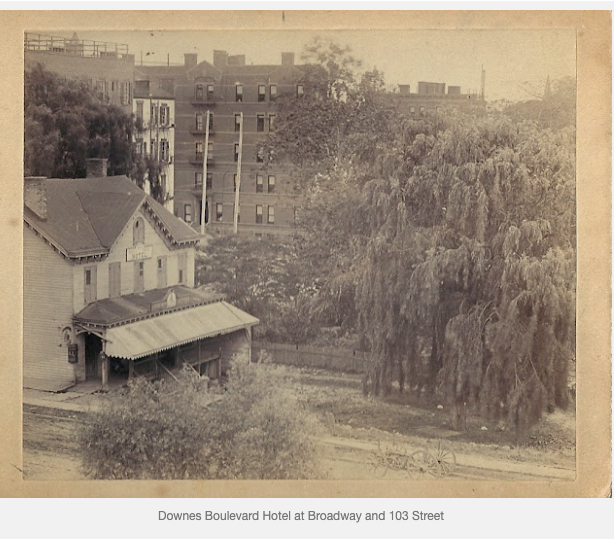

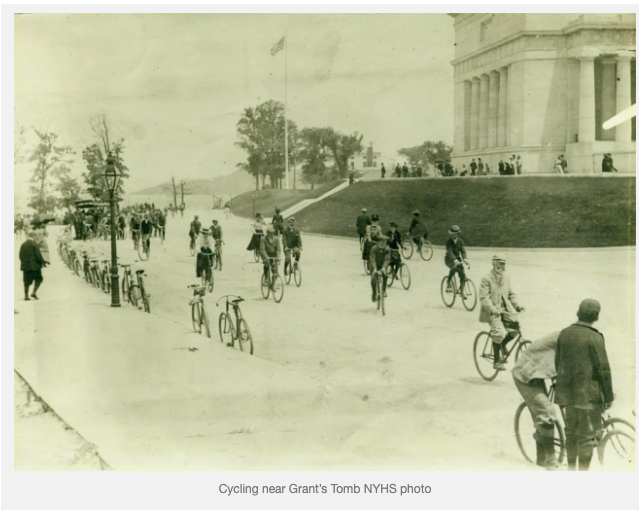

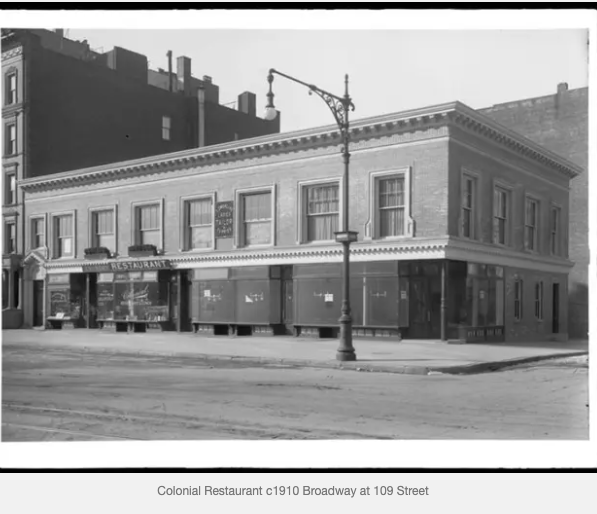

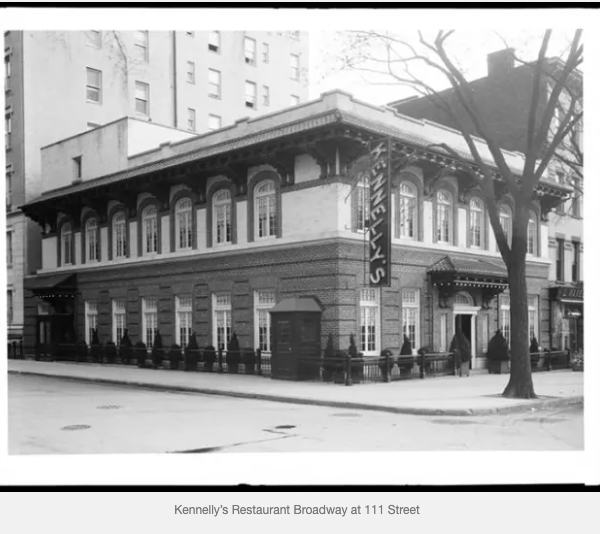

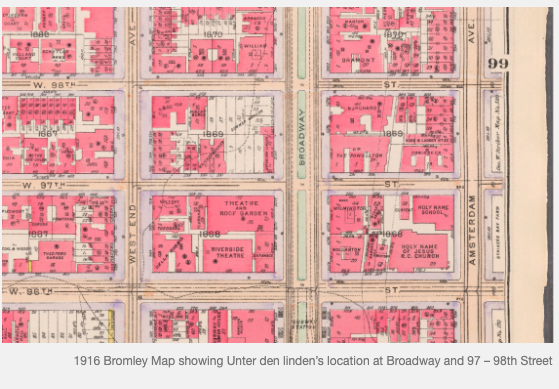

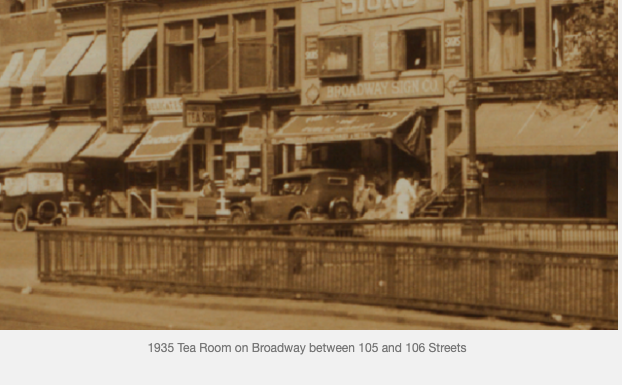

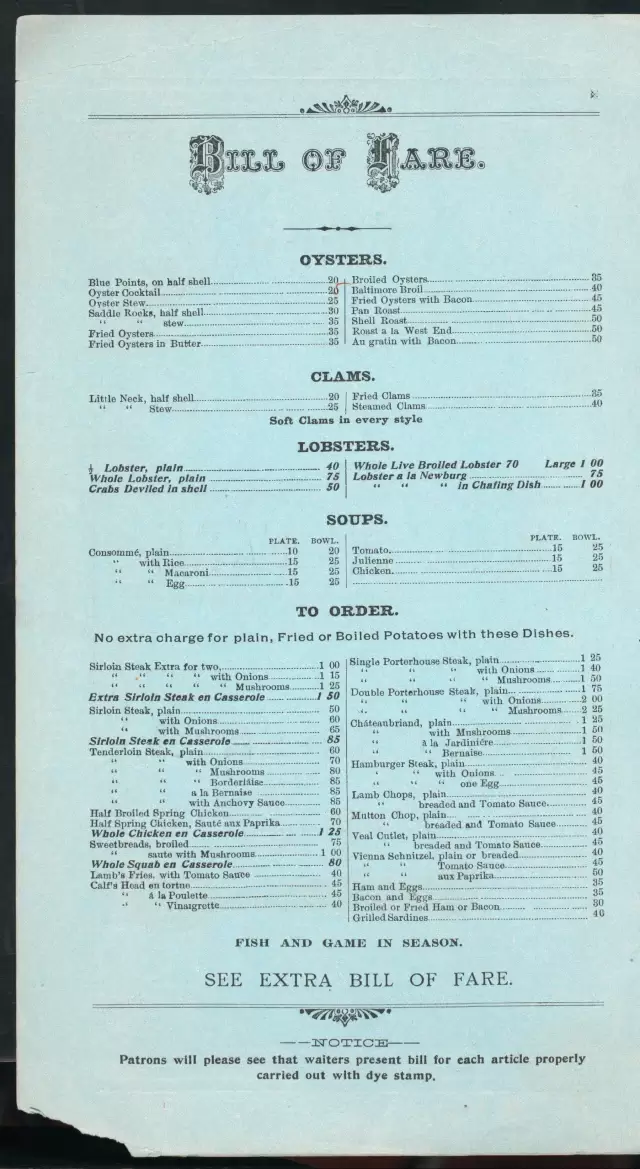

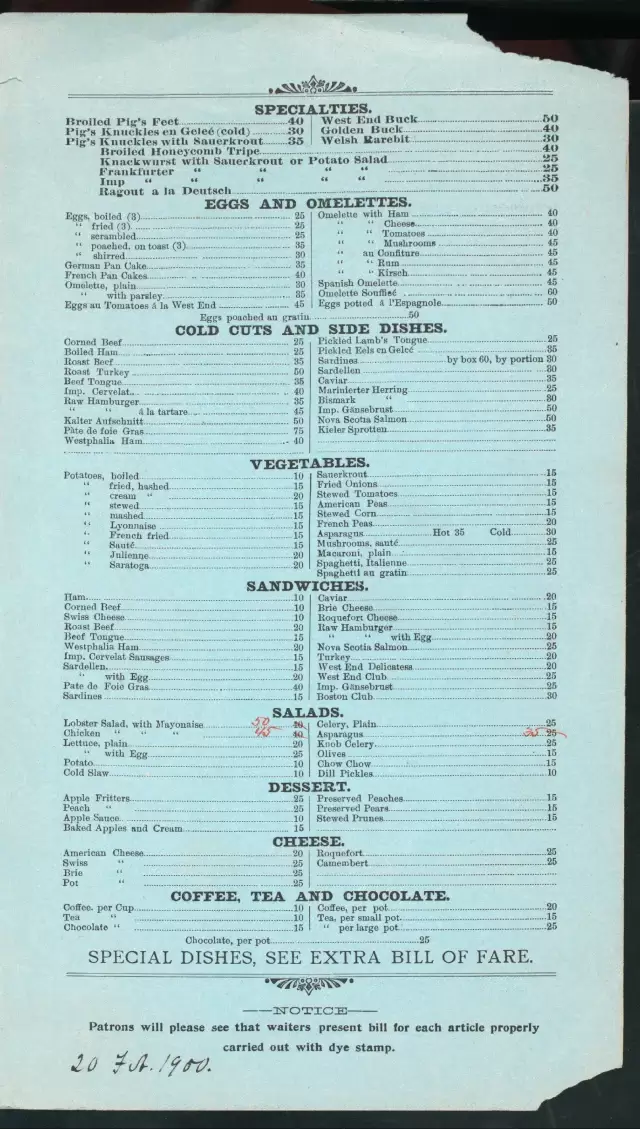

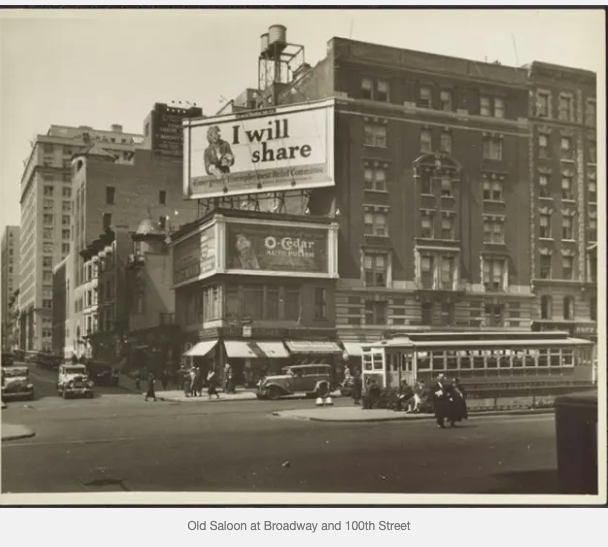

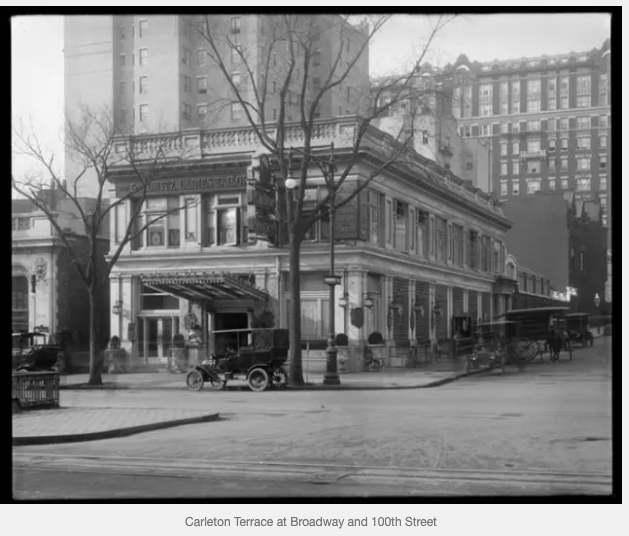

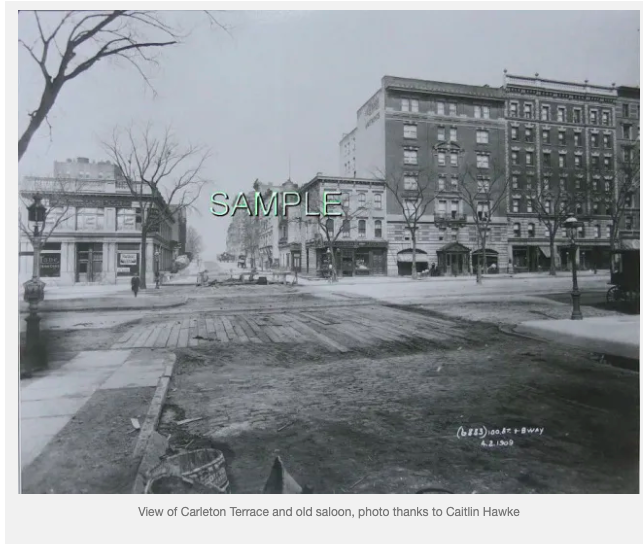

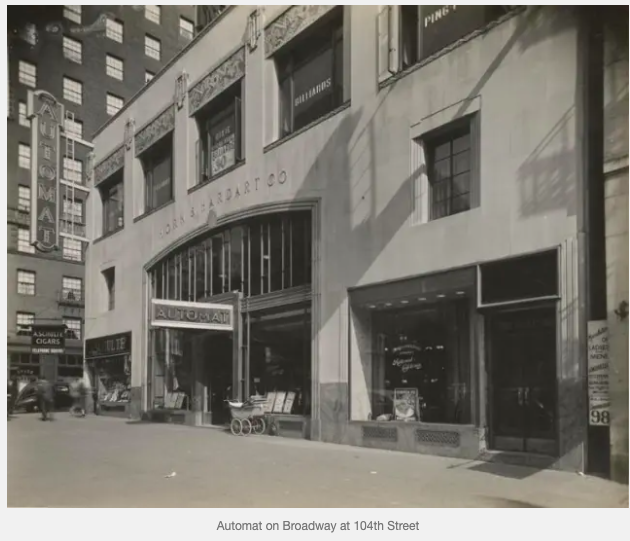

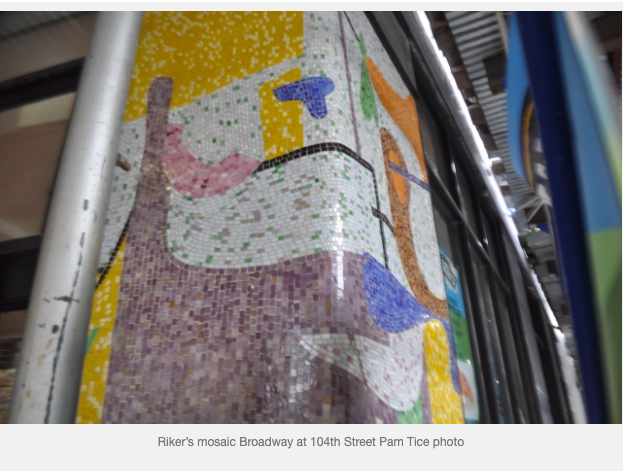

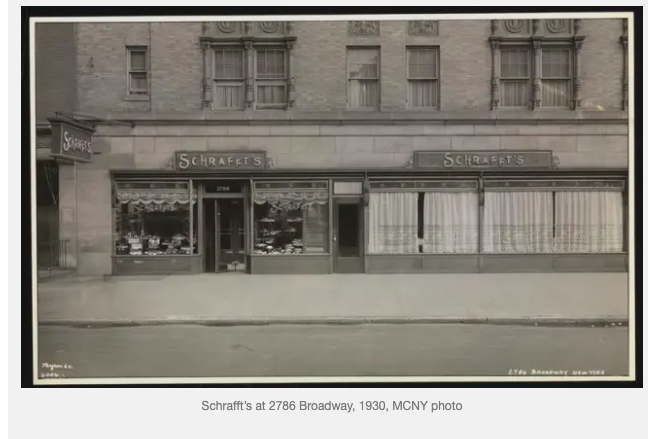

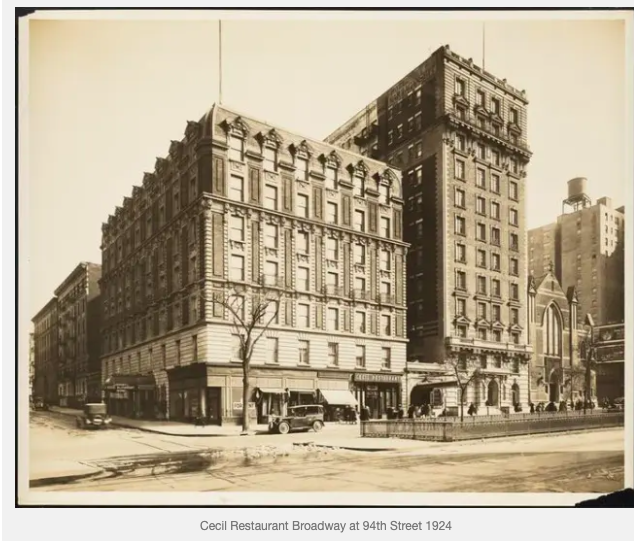

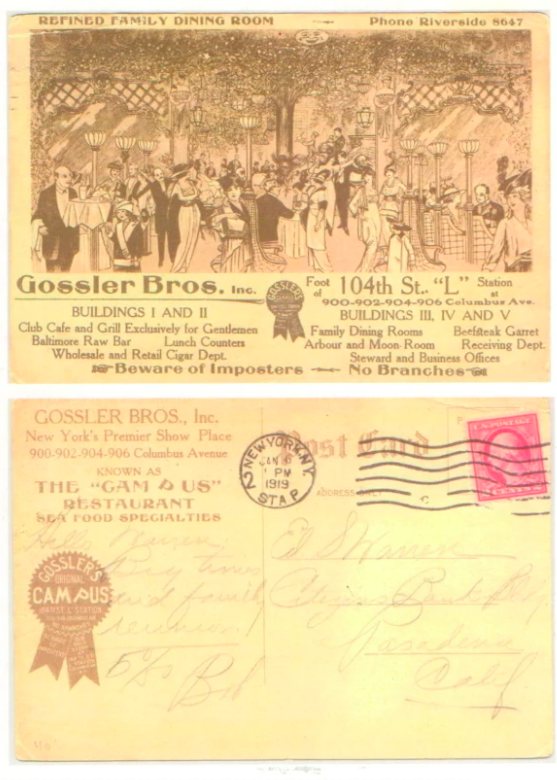

On March 7, 1970, in the mid-afternoon, there was a 96% totality solar eclipse in New York City that West Siders may remember, as many people gathered in Riverside Park to experience it. This one was made especially memorable as it was the first to be broadcast in color. (The first televised in black and white was in 1950.) West Sider, Carly Simon, may have been inspired by this event when she wrote her hit “You’re so Vain,” singing “you flew your Lear jet up to Nova Scotia/to see a total eclipse of the sun.” Sources The New York Times archive Photo posted on http://mysticseaportcollections.blogspot.com/2015/02/cold-and-darknyc-january-24-1925.html American Museum of Natural History Planetarium blog: http://www.amnh.org/our-research/hayden-planetarium/blog/84-years-ago-the-sun-blinked-out/ Other newspapers available on www.genealogybank.com. Here is another piece written on places that used to be in the Bloomingdale neighborhood, written by Pam Tice, a member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group’s Planning Committee. Thanks go to Chuck Tice and Marjorie Cohen as editors. New York’s City’s restaurant history is a popular topic for many social historians. They have traced New York’s history of famous restaurants from the 1830s Delmonico’s on the corner of Beaver and William Streets, (moving twice as the city grew), to the lobster palaces of Times Square, to the bohemian dining of Greenwich Village. Worked into this panoply is the history of a developing middle class, the creation of social spaces where women could meet outside the home, the development of dining places for the growing office workforce of New York, and the growing acceptance of the food and cooking of the millions of immigrants who came to the city. This post is a collection of “snippets” about restaurants found while focusing on Broadway from 86th to 110th Streets, with more emphasis north of 96th Street. The popular Automat and Schrafft’s located there already have well-researched general histories. Many old photographs of the city contain images of restaurants. Restaurant information is found in advertisements, appears in historic postcard collections, and in The Real Estate Record and Guide. Searches through the menu collection of the New York Public Library revealed little for our Bloomingdale neighborhood. In the early twentieth century, there were no “restaurant reviews” as we have today; a restaurant was mentioned only when an incident occurred there, or changed owners, or was sold. Restaurants as a regular feature on the city blocks of Bloomingdale did not begin until the population grew enough to produce dining patrons. From the earliest days of the Bloomingdale Road—later the Boulevard, finally becoming Broadway—there were inns, and they served food, but these were not restaurants in the modern sense with food offered throughout the day and evening, with a number of dishes to choose from. Typically, in an inn, the owner served a single meal at an appointed time, and the eating was communal. Saloons had been around for a long time, but their food was merely an accompaniment to drinking The Downes Boulevard Hotel was located at Broadway and West 103rd Street. The Jones homestead between 101st and 102nd west of West End Avenue became the Abbey Hotel in 1844, but it only lasted until 1857. In the 1890s, when the bicycling craze swept New York City, the enthusiastic cyclists streamed up Riverside Drive and Broadway, to a number of “bicycle gardens” that served them, including Schaaf’s Bicycle Inn at the Boulevard/Broadway and 112th Street. Some of these became the saloons and dance halls of Little Coney Island (click for previous post) along 110th Street that so irritated the real estate developers. Close to the Bloomingdale neighborhood was the Claremont Inn, which Marjorie Cohen wrote about in an excellent piece published in the West Side Rag. People out for a carriage drive and the cyclists relaxed at the Inn in the 1890s, and then, a little later, automobile touring groups found their way there. The Inn was recommended for summer dining in guidebooks in the 1930s-1940s before its demise in 1951.C This photo (below) shows the Colonial Restaurant on Broadway at the southwest corner of West 108th Street. The photograph is dated circa 1910 which makes sense because the 1902 property map for that corner shows no building; on the 1912 map there is a building taking up about half the block. The Columbia Spectator for November 1912 had an advertisement for the Colonial Restaurant at Broadway and 85th Street, with a branch at “Broadway near 110th Street. Steaks, chops and seafoods are featured, and the management also extends to the Oxford Lunch at 2546 Broadway near West 96th Street.” From the earliest days on Morningside Heights, Columbia University students hung out at the Lion Palace on Broadway at 110th Street, which was the local saloon of the Lion Brewery located on Columbus Avenue at 107 to 109 Streets. The Lion Palace evolved into a theater, and then a movie house, the Nemo, by 1916. Another Columbia neighborhood restaurant was Kennelly’s, pictured here. Their ads in the Columbia Spectator ran from 1916 to 1922. Between 97th and 98th Streets on the west side of Broadway was a well-known German beer garden spot, the Unter den Linden, named for the boulevard in Berlin. Here it is on a 1916 map, showing a lot of empty space around the building, space that served outdoor diners in warmer weather. A 1933 article in The New York Times about New York’s German beer gardens mentions this particular location, as does Peter Salwen in his book Upper West Side Story. Salwen describes the shade trees, small tables and the colored lights overhead: “In May and June when the lindens shed their sweet-scented white blossoms, you could drop in after dinner to enjoy waltzes from the German band in a setting that was almost rural.” This was also the type of place that attracted the cyclists on Sunday afternoon jaunts. Michael Susi has a postcard view of the Unter den Linden on page 72 of his Upper West Side book. By 1919, however, the Real Estate Record and Guide is reporting the sale of this corner where a 16-story apartment-hotel still stands today. German and Austrian influence on the neighborhood is also reflected in this photo of Broadway at 104th Street, showing “Old Vienna” and “New Vienna” restaurants. This food was one of the first ethnic cuisines adopted by Americans, which eventually stretched from hot dogs to coffee cake and strudels, and to potato salad. In these early 20th century restaurants, no doubt there was Wiener schnitzel and apfelstrudel on the menu. Another type of early 20th century restaurant is the tea room, a place where women could find light refreshment, either alone or together. Hard to imagine now, but “proper women” could not appear in a restaurant alone, or even with a female friend, in the early years of the 20th century. Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s daughter, Harriot Blatch, sued the Hoffman House in 1907 for refusing to seat a friend and herself. She lost her suit in 1909, and even an attempt by the New York State legislature to end this discrimination failed. Finally, restaurant owners recognized that a new generation of women—more independent, educated, and earning an income —should be accommodated, and they became acceptable customers. But for years, a woman dining alone was advised to “bring a book” lest anyone think she was there for a nefarious reason. To accommodate women, department stores began to offer tea-room service. The Women’s Exchange Movement, established to help “gentlewomen” who had fallen on hard times, began to serve tea and light lunches at their locations, where women sold their hand-made items, like baby clothes, linens, and jam. The Schrafft’s restaurants, discussed below, grew out of this need to provide safe places for women diners. Here is a tea room in our neighborhood in 1935, on Broadway, between 105th and 106th Streets. Restaurants developed in many of the apartment-hotels that became residential choices on the West Side. The Clendening Hotel, at Amsterdam Avenue and 103rd Street, the Marseilles at Broadway and 103rd Street, the St. George at 102nd Street, and many others had dining rooms for their guests and other customers. In their advertisements, hotels offered the European Plan (accommodation, no food) or the American Plan (room rent with three meals). At the St. George, lunch was priced from 40 cents, and dinner from 60 cents. This one from the West End Hotel on 125th Street is typical of this type of restaurant. At both the northwest and southwest corners of 100th Street and Broadway there were—and still are—restaurants. The building that houses the Metro Diner today was established in 1871 as the Boulevard House; Peter Doelger bought it in 1894, adding to his line of saloons. For a while it became “Conroy’s”—my friend Rich Conroy discovered one of his ancestors had lived upstairs there, Irish-born John Conroy, with his wife and four children. The building has never been landmarked, but it has been altered, and steel-beamed, and it’s a miracle that it still exists. On the southwest corner, the two-story Carleton Terrace restaurant stood until, in 1923, the 15-story Carleton Terrace Hotel was built, and offered a roof-garden dining spot, another restaurant style of that era. Rooftop dining and dancing was popular in the hot summer days before air conditioning. Michael Susi includes a photo of the Carleton roof in his book on page 72. The Carleton Terrace later became the Whitehall Hotel. Another popular restaurant, Archambault’s, was at the southwest corner of Broadway and 102nd Street. The owner, F. A. Archambault, was the “proprietor” of the Hotel Belleclaire at 77th Street—also the site of a popular roof-garden restaurant. Archambault’s lasted for several years, gaining a newspaper mention in 1913 when Mrs. Strauss’ maid, “melancholic,” tried to jump from the fourth floor of the apartment building that housed the restaurant, bringing all the diners out to the street. Mrs. Strauss hung on to her maid, and she was rescued. In 1929, William Childs of the Childs-restaurant family bought the restaurant to develop a chain of restaurants patterned after foreign destinations, naming it “Old Algiers.” The opening of the IRT subway along Broadway in 1904 spurred the growth of the neighborhood. Early immigrants who had settled on the Lower East Side moved to the neighborhood, bringing what one writer called the Lower East Side’s “gift of the Jewish deli.” These food stores and restaurants soon became a popular feature. I could not find one north of 96th Street of the size and reputation of those stores at 86th Street and further south. The word “delicatessen” was of German origin, and meant a place that served and sold cured meats and sausages. Barney Greengrass, on Amsterdam at 86th Street, with both meat and fish offerings, was established in 1908, and is still there, as is Fine and Shapiro on 72nd Street. Artie’s at 83rd Street and Broadway is attempting a revival of this style. Of course the new residents brought the dairy restaurants too. Steinberg’s Dairy Restaurant was on Broadway’s east side between 81st and 82nd; their sign was recently uncovered when the Town Shop moved, causing neighborhood memories to reawaken. But just because I did not find a photo or a mention i An eating craze that began before the turn of the 20th century was an adaptation of authentic Chinese food: chop suey. I found an 1911 advertisement for a chop suey place in the Columbia neighborhood, and others may have existed on our Bloomingdale blocks. Much later, when Americans had been introduced to many other Chinese cuisines, our neighborhood became well-known for its Sichuan restaurants. Much has been written about fast-food dining getting its start in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Our neighborhood developed three restaurants operating in this mode. At first I wondered why the Automat and Schrafft’s chose their locations, since we are not a commercial neighborhood of offices and big department stores. However, we were an area with a dense population, and had lots of movie theaters between 96th and 110th Streets, including the Nemo, the Olympia, the Midtown, the Stoddard, the Riviera, and the Riverside. Pre- and post-theater dining spots were necessary. The Automat building on the southeast corner of Broadway and 104th Street is one of our neighborhood landmarks today. Built in 1930, it lasted until 1954. The popular Automats introduced “waiter-less dining,” standardized and predictable food items, and the added attraction of the mechanized offering of food when nickels were put in a slot. Joseph Horn and Frank Hardart brought the Swiss-invented, German-manufactured equipment to Philadelphia, and then branched out to New York City in 1912. When the last Automat closed in 1991 (on Third Avenue at 42nd Street) many nostalgic articles were written. Our Automat at 104th Street had the distinction of being the site of the mysterious deaths of two persons in 1934. A despondent man committed suicide by placing cyanide in a roll, and, after leaving it on a plate at a table to go to the men’s room, a neighborhood woman took the remains and also died. This story has become a cautionary tale, with the lesson of never, ever eating any leftovers in a restaurant. On the northeast corner of West 104th Street, the Broadway View Hotel was built in the 1920s, replacing the Metropolitan Tabernacle that had been located there. Lost in foreclosure in 1933, the hotel became the Regent, and a Riker’s took the corner store in 1947. This chain of what we would call a coffee shop today had locations all around Manhattan, and even had its own dishes, as pictured. One in Greenwich Village has been identified as the place Edward Hopper chose to make his famous painting “Nighthawks,” a work of art that has come to represent the loneliness of the large city. Our neighborhood Riker’s is best known for hiring ceramicist Michael Spivak to design swirling mosaic abstract murals for its corner columns, an artwork that has (miraculously!) partially lasted to today. The scaffolding currently around the building makes a good photo harder to take today, but here is a portion of the artwork. Our neighborhood Schrafft’s was located on the ground floor of the apartment building stretching from 107th to 108th Streets on the east side of Broadway, today the space occupied by the Garden of Eden. There was another one at Broadway and 82nd Street, where Barnes and Noble is now located. Schrafft’s began as a candy shop owned by a Bostonian, William G. Schrafft. Frank Shattuck owned a chain of the stores, and it was his sister who suggested providing light lunches for “ladies” and the idea took off, particularly in New York’s shopping districts where there were many lunching (and working) women who wanted a place to eat where they would be comfortable. The shops were a “retreat” from the bustle of the city, and served predictable comfort food, like creamed chicken and lobster Newburg, but also offered banana splits and ice cream sundaes, as the “special treat” that dining out could provide, and a place to bring a deserving child. All of them had candy counters ready to provide a take-home box of chocolates. They became cultural icons, with The New Yorker providing regular comical snippets “overheard at Schrafft’s.” Even W. H. Auden composed a poem in 1947 “In Schrafft’s.” Finally, there was a restaurant called Cecil at the Hotel Narraganset on Broadway at 93rd Street. Moving away from Broadway, just a couple of other dining spots in the Bloomingdale neighborhood include:

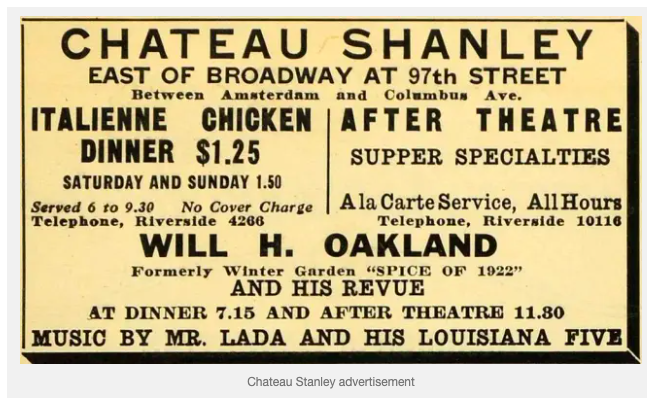

Chateau Stanley at 163 West 97th Street where PS 163 is located today. Before Chateau Stanley was located there in the 1920s, the space was Peter’s Italian Table D’Hote Restaurant in 1910, a place I was glad to find, as Italian dining was another “foreign” food that Americans adopted as restaurants developed early in the twentieth century. Michael Susi has photos of both in his postcard collection book, page 91. Sources

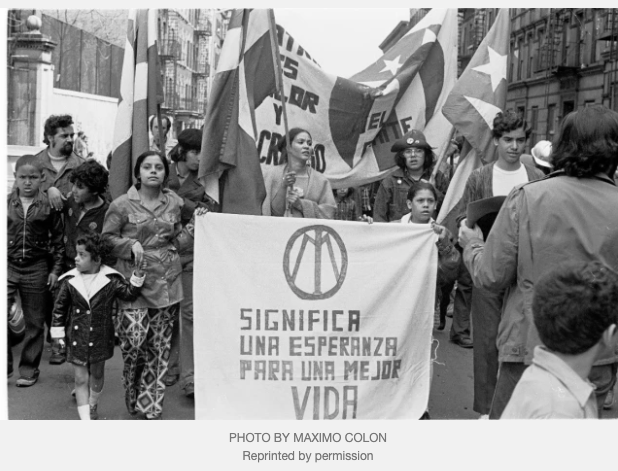

Michael V. Susi. The Upper West Side. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2009 James Trager. West of Fifth: The Rise and Fall of Manhattan’s West Side. New York: Atheneum, 1987 Peter Salwen. Upper West Side Story, A History and Guide. New York: Abbeville Press, 1989 Michael Lesy and Lisa Stoffer. Repast: Dining Out at the Dawn of the New American Century 1900-1910. New York: W.W. Norton, 2013 Michael and Ariane Batterberry. On The Town in New York. New York: Routledge, 1999 The New York Times archive The New Yorker archive Real Estate Record and Guide available online The Library of Congress newspaper archive, Chronicling America Website: www.restaurant-ingthroughhistory.com Digitized photo and map collections of the New York Public Library Digitized photo collection of The Museum of the City of New York Numerous sites found while Googling restaurant names. On June 7, 2016, the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group presented a program about political activism on the UWS in the 1960s and 70s. The main speaker was Rose Muzio, Professor of Politics at SUNY Old Westbury and author of Radical Imagination, Radical Humanity: Puerto Rican Political Activism in New York. The program was rich in detail. The following is a summary of some of that program only based on notes I took during the presentations. — Jay Hauben Rose Muzio, who had been a member of El Comité-MINP which started in the UWS in 1970, began her presentation by describing the harsh conditions in NYC for Black and Latinos in the 1950s and 1960s. She asked why in the 1940s and 1950s did so many Puerto Ricans leave their beautiful island. Her answer was PR is a colony. Mainland companies took much PR agricultural land for manufacturing leading to high unemployment. Local governments encouraged migration so as to deal with the unemployment and discontent. For a while there were manufacturing jobs in NYC. When NYC deindustrialized in the 1960s and 1970s, more than 500,000 jobs were lost. Unemployment among Blacks and Puerto Ricans was two times the overall unemployment rate in NYC. Meanwhile school segregation was increasing and Blacks, Puerto Ricans and Dominicans were on average charged higher rents for worse housing than other people.

But this was a time of decolonization and rising expectations around the world. The anti colonial movements, the Cuban Revolution for a more equal society and the anti-VN War movement were inspirational. Resistance groups and movements in the US arose to oppose economic inequality and racism, e.g., the Black Panthers, the Brown Berets, and in NYC CORE, the Young Lords, student groups at Columbia and CUNY and worker groups. After emerging in 1969 in East Harlem, a branch of the Young Lords advocated for community control and independence for Puerto Rico. In a famous garbage offensive they gathered the garbage that NYC did not remove from East Harlem streets and made a big heap on Third Ave, lighting it on fire. The resulting media coverage raised the profile of Puerto Rican grievances. Rose Muzio gave this as background for the UWS squatters movement called Operation Move-In* that opposed urban renewal (urban removal). In 1970, after a young boy, Jimmy Santos, died from carbon monoxide poisoning in a first-floor apartment on West 106th Street, anger exploded. People broke into buildings that were boarded up waiting for demolition as part of urban renewal and occupied them by moving families in. This was followed by a group of young Puerto Rican and one Dominican softball players occupying a storefront on Columbus Ave near 88th Street. Those young Latinos became El Comité. Over time El Comité transformed into a political group which won the first district-wide bilingual program. That program benefited all the mono-lingual students. El Comité forced Channel 13 which was a public TV station (PBS) to do a series on Latinos in NYC. They did that by breaking into the station while it was on the air and making a statement that was broadcast live. El Comité started a Latina unity organization that gave strength to women to take on many challenges. El Comité formed a Black and Puerto Rican construction workers coalition which forced the city to open its construction jobs across race lines. They issued a bi-weekly newsletter, Unidad Latina, which routinely contained articles addressing local issues as well as the struggle for independence in Puerto Rican. There were also projects that did not succeed but El Comité inspired people and drew them into more collective action. Rose Muzio ended her presentation by saying El Comité helped her set the foundation for her life and her life’s work and continues to inspire former members and those touched by the group which disbanded in 1986. Next, Máximo Rafael Colón showed many of the wonderful photographs he took documenting the marches and struggles in the 1960s and beyond. In his photos were many of the activists that went on to be leaders in the movements that emerged. Interesting to me many of them became journalists** like Pablo Guzman and Juan Gonzales. Colón called attention to the Puerto Rican political prisoners over the years and especially Oscar López Rivera who is still in prison after 35 years. Oscar López Rivera committed no violent crime. His crime was called sedition, thinking that there has to be a change, independence for Puerto Rico. Colón called Oscar López Rivera the Nelson Mandela of the Puerto Rican people. In 1971, the Young Lords and El Comité objected to the Puerto Rican Day Parade appearing as a spectacle of Puerto Rican compliance with the institutions of oppression. Some of the photos showed the fight against the Parade Committee. One photo showed activists marching in the parade. Colón also called our attention to the Broadway Local whose members were white youth facing the same contradictions and fighting for progressive change and to the East Harlem Rainbow Coalition which marched in support of the presidential candidacy of Rev Jesse Jackson. There followed a panel of four women, Carman Martell, Ana Juarbe, Annie Lizardi and Lourdes Garcia who lived and worked in the UWS and were politicized by the movement all around them. Coincidentally two of the women moved from PR to around 101nd St in the early 1950s. One of the women was three years old at the time the other was seven when they arrived from PR. The four women told about how they used their lives for social purposes. The last of the four panelists was Lourdes Garcia who told many details of the economic situation in PR today. It was clear that the harsh conditions in the UWS in the 1950s and 1960s, the political activism these conditions gave rise to and the struggle for Puerto Rican Independence helped these women and many other people become conscious political actors for the rest of their lives. *1970 Squatters’ Movement Factors such as urban renewal, the physical expansion of major institutions like Columbia University, and the lack of sufficient public housing made it very difficult for low-income families to find housing in New York City during the late 1960s. During the summer of 1970, communities responded with a squatter movement which installed over 300 families in vacant apartments across the city. Most of these squatted apartments, frequently slated for demolition in urban renewal areas, were owned by the city or by large institutions. Led by African-American and Latino families, this squatter movement received support from Met Council on Housing in the form of help with repairs, negotiations with landlords and fighting evictions. Squatters succeeded in delaying institutional expansion into Morningside Heights. Some landlords yielded to demands, providing services in squatted apartments and for a few, the right to remain in their new homes. The squatter movement gained significant media coverage, giving exposure to critical housing issues such as urban renewal, property speculation, long-term vacancies and the need for affordable housing. ————————————————- ** Legendary New York City newspaper columnist Jimmy Breslin once joked that the Young Lords, a militant Puerto Rican group, produced more great journalists than Columbia University’s journalism school. Several alumnae of the Young Lords did go on to careers as journalists after raising hell in the streets of Spanish Harlem. A few even made their marks in public media. How a militant Puerto Rican activist group influenced public media Here’s another post on something that no longer exists in our Bloomingdale neighborhood. The author, Pam Tice, is a member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group’s Planning Committee.

For a short period, perhaps less than five years, West 110th Street became an entertainment district known as “Little Coney Island.” The story of its development and demise is a New York story with real estate, politics, the Police Department, vice and corruption, changing social values, and class conflict. The Upper West Side rapidly developed in the last two decades of the 19th century and the first two of the 20th century. Very quickly, sparsely-placed wood-frame houses were replaced by brownstones and tenements, and, over time, larger and larger apartment buildings. Development initially followed the new El train, spreading out from the station stops as land was sold and developed. Up on 110th Street, real estate development proceeded a bit more slowly. Morningside Park was designed, but took a long time to build out, even after Andrew Haswell Green’s money-saving idea to retain the rocky wall between Morningside Heights and the Harlem Plain. On one end of 110 Street, near Central Park, the elevated train’s “suicide curve” provided a thrill to riders as the train moved from Ninth to Eighth Avenues. There was no stop there until 1903; when it did open, the speed of the trains was decreased on the curve, lessening the thrill of the ride. |