|

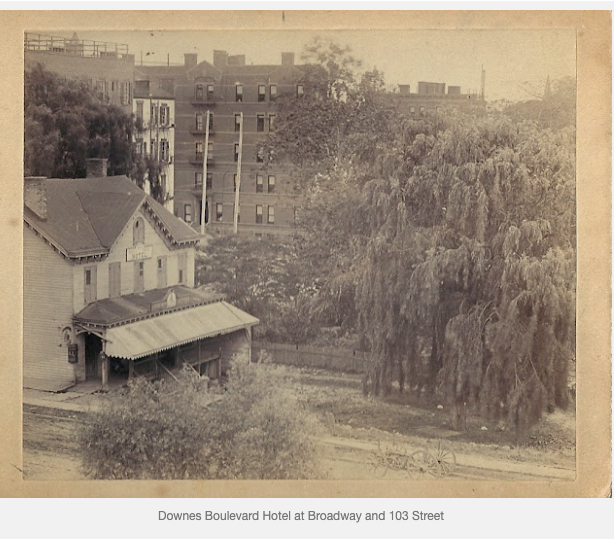

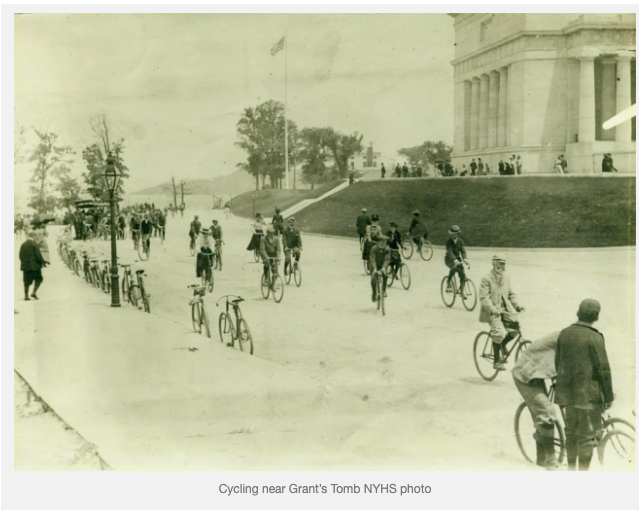

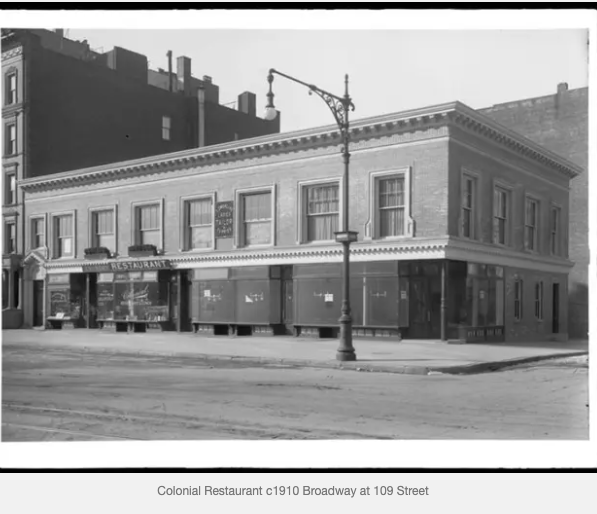

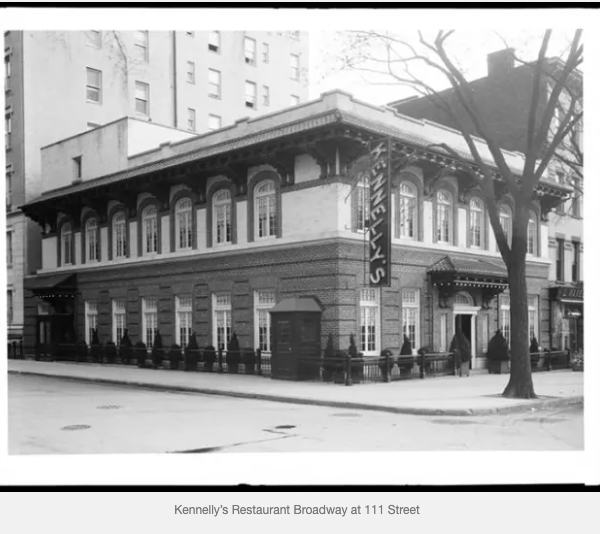

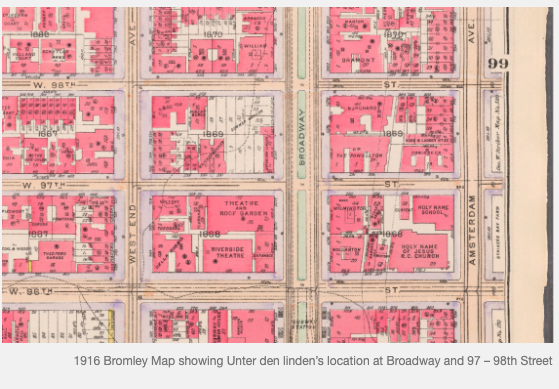

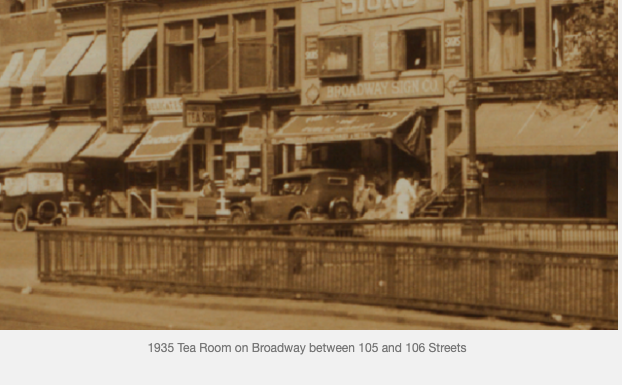

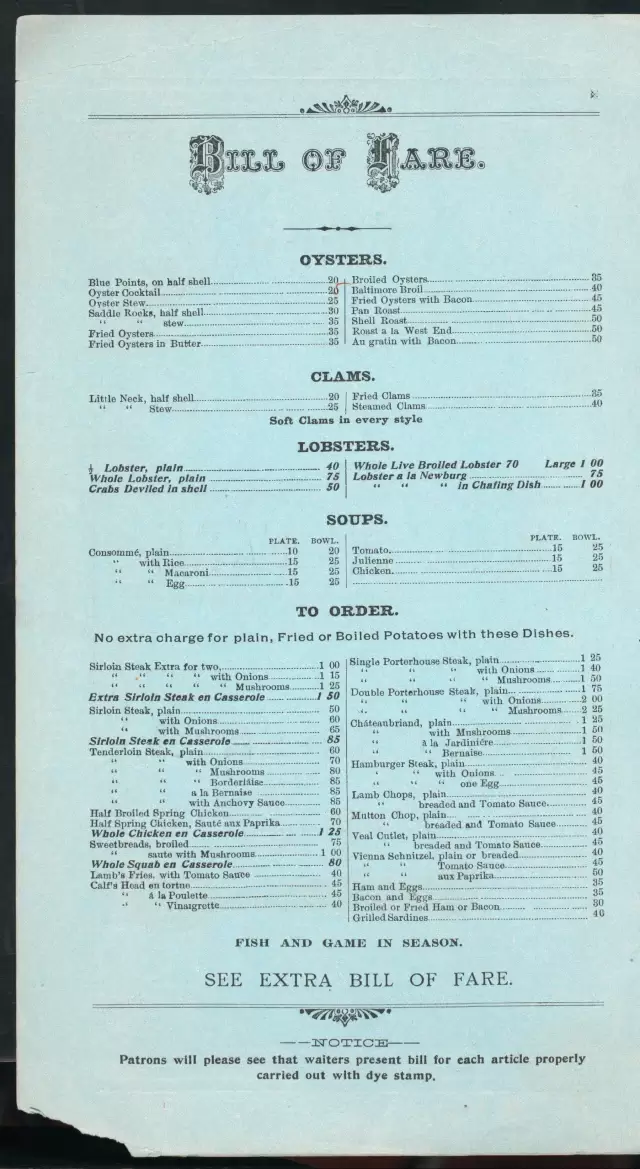

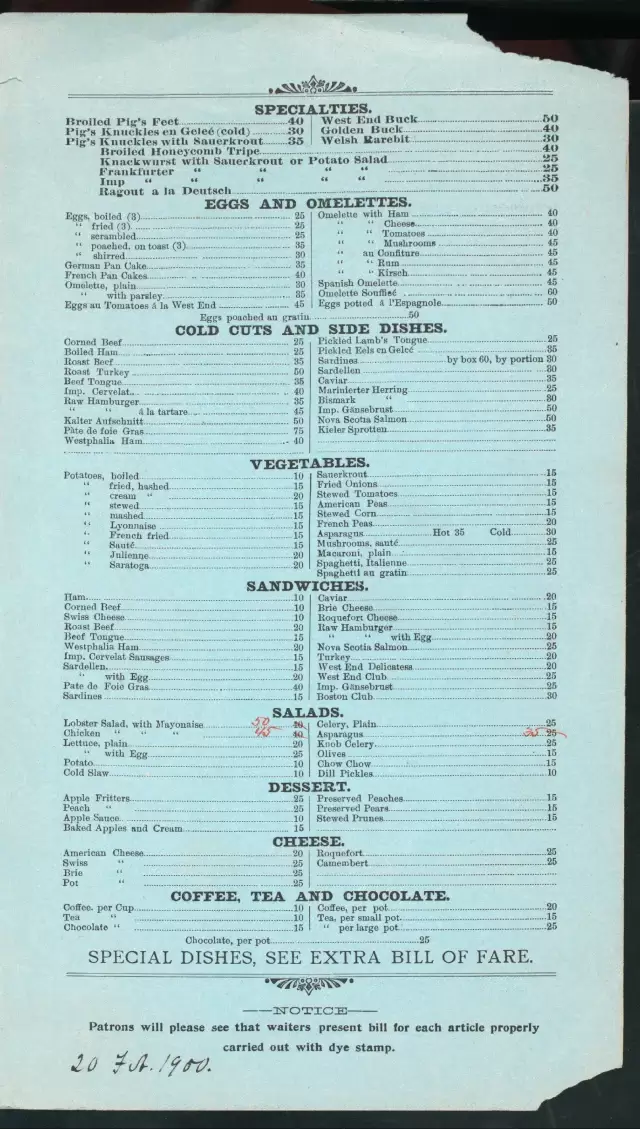

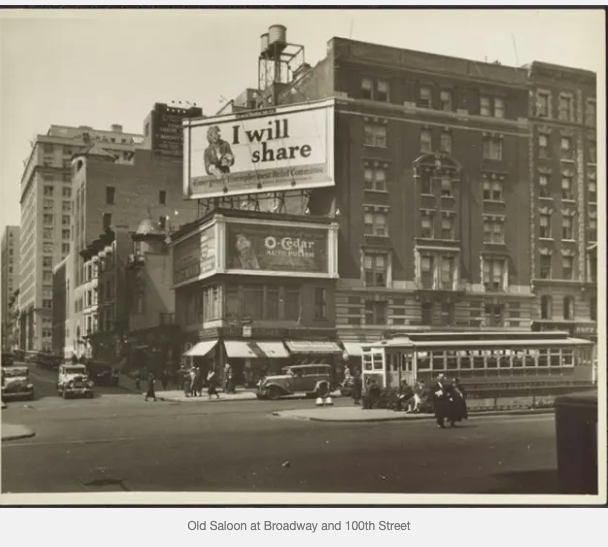

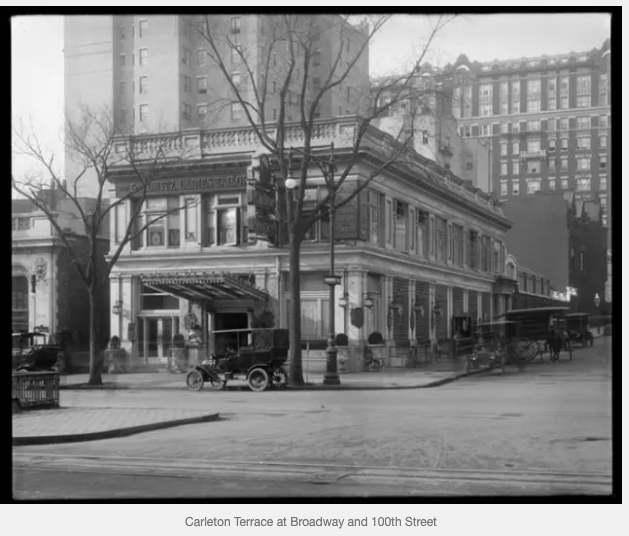

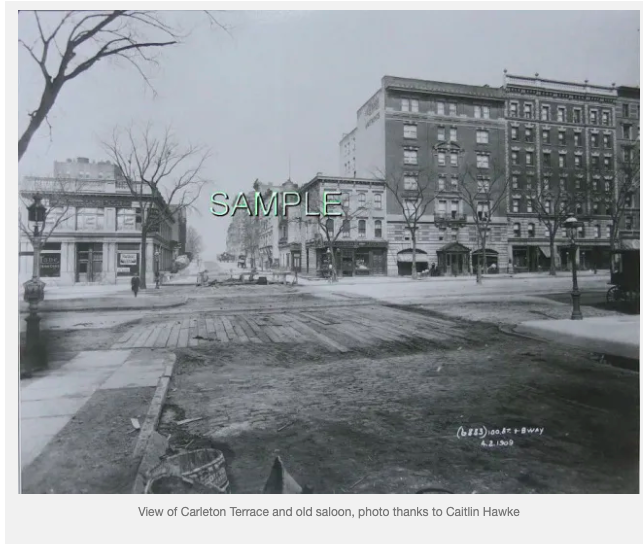

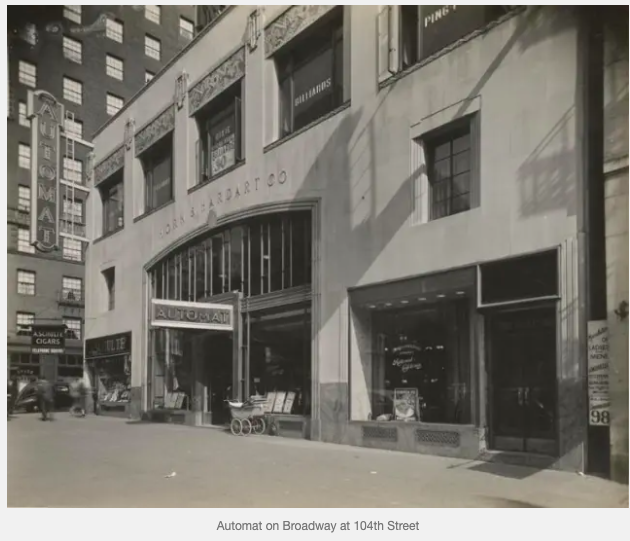

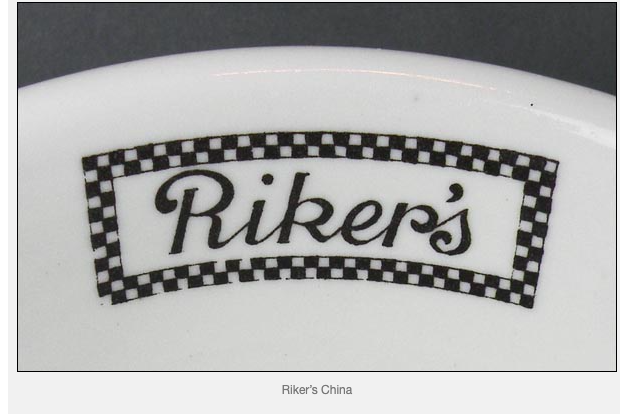

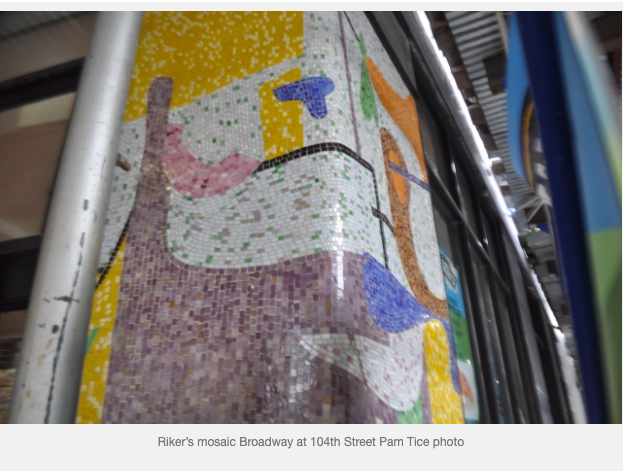

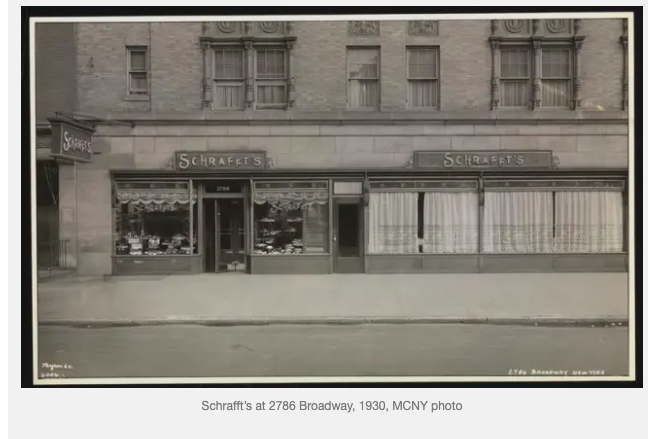

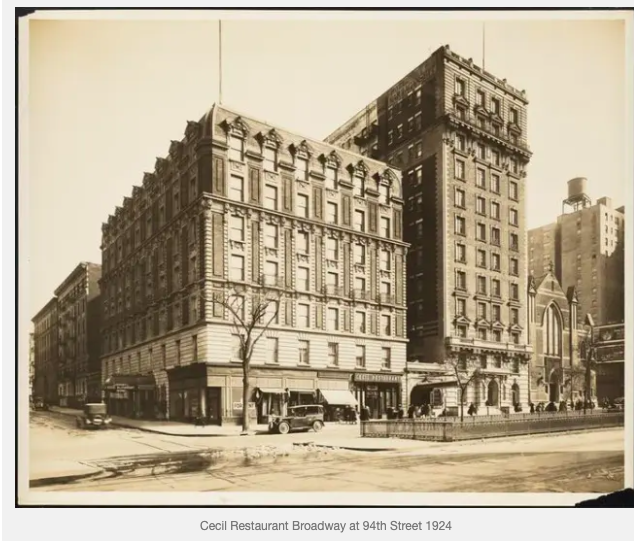

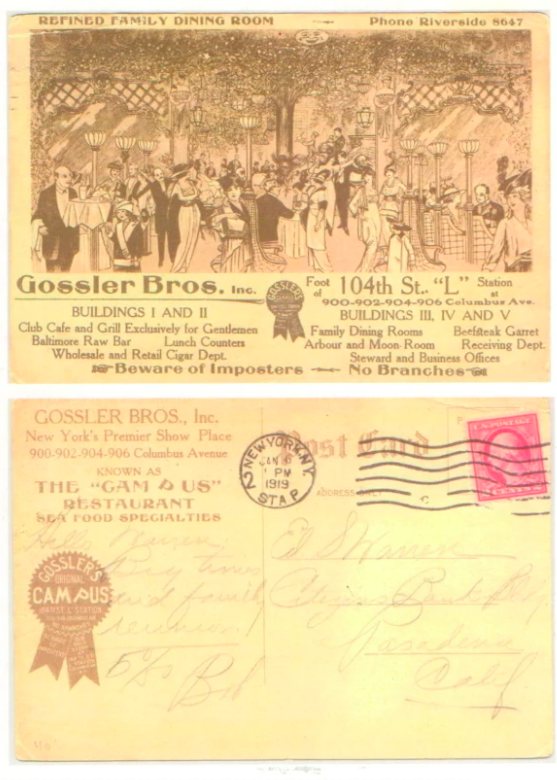

Here is another piece written on places that used to be in the Bloomingdale neighborhood, written by Pam Tice, a member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group’s Planning Committee. Thanks go to Chuck Tice and Marjorie Cohen as editors. New York’s City’s restaurant history is a popular topic for many social historians. They have traced New York’s history of famous restaurants from the 1830s Delmonico’s on the corner of Beaver and William Streets, (moving twice as the city grew), to the lobster palaces of Times Square, to the bohemian dining of Greenwich Village. Worked into this panoply is the history of a developing middle class, the creation of social spaces where women could meet outside the home, the development of dining places for the growing office workforce of New York, and the growing acceptance of the food and cooking of the millions of immigrants who came to the city. This post is a collection of “snippets” about restaurants found while focusing on Broadway from 86th to 110th Streets, with more emphasis north of 96th Street. The popular Automat and Schrafft’s located there already have well-researched general histories. Many old photographs of the city contain images of restaurants. Restaurant information is found in advertisements, appears in historic postcard collections, and in The Real Estate Record and Guide. Searches through the menu collection of the New York Public Library revealed little for our Bloomingdale neighborhood. In the early twentieth century, there were no “restaurant reviews” as we have today; a restaurant was mentioned only when an incident occurred there, or changed owners, or was sold. Restaurants as a regular feature on the city blocks of Bloomingdale did not begin until the population grew enough to produce dining patrons. From the earliest days of the Bloomingdale Road—later the Boulevard, finally becoming Broadway—there were inns, and they served food, but these were not restaurants in the modern sense with food offered throughout the day and evening, with a number of dishes to choose from. Typically, in an inn, the owner served a single meal at an appointed time, and the eating was communal. Saloons had been around for a long time, but their food was merely an accompaniment to drinking The Downes Boulevard Hotel was located at Broadway and West 103rd Street. The Jones homestead between 101st and 102nd west of West End Avenue became the Abbey Hotel in 1844, but it only lasted until 1857. In the 1890s, when the bicycling craze swept New York City, the enthusiastic cyclists streamed up Riverside Drive and Broadway, to a number of “bicycle gardens” that served them, including Schaaf’s Bicycle Inn at the Boulevard/Broadway and 112th Street. Some of these became the saloons and dance halls of Little Coney Island (click for previous post) along 110th Street that so irritated the real estate developers. Close to the Bloomingdale neighborhood was the Claremont Inn, which Marjorie Cohen wrote about in an excellent piece published in the West Side Rag. People out for a carriage drive and the cyclists relaxed at the Inn in the 1890s, and then, a little later, automobile touring groups found their way there. The Inn was recommended for summer dining in guidebooks in the 1930s-1940s before its demise in 1951.C This photo (below) shows the Colonial Restaurant on Broadway at the southwest corner of West 108th Street. The photograph is dated circa 1910 which makes sense because the 1902 property map for that corner shows no building; on the 1912 map there is a building taking up about half the block. The Columbia Spectator for November 1912 had an advertisement for the Colonial Restaurant at Broadway and 85th Street, with a branch at “Broadway near 110th Street. Steaks, chops and seafoods are featured, and the management also extends to the Oxford Lunch at 2546 Broadway near West 96th Street.” From the earliest days on Morningside Heights, Columbia University students hung out at the Lion Palace on Broadway at 110th Street, which was the local saloon of the Lion Brewery located on Columbus Avenue at 107 to 109 Streets. The Lion Palace evolved into a theater, and then a movie house, the Nemo, by 1916. Another Columbia neighborhood restaurant was Kennelly’s, pictured here. Their ads in the Columbia Spectator ran from 1916 to 1922. Between 97th and 98th Streets on the west side of Broadway was a well-known German beer garden spot, the Unter den Linden, named for the boulevard in Berlin. Here it is on a 1916 map, showing a lot of empty space around the building, space that served outdoor diners in warmer weather. A 1933 article in The New York Times about New York’s German beer gardens mentions this particular location, as does Peter Salwen in his book Upper West Side Story. Salwen describes the shade trees, small tables and the colored lights overhead: “In May and June when the lindens shed their sweet-scented white blossoms, you could drop in after dinner to enjoy waltzes from the German band in a setting that was almost rural.” This was also the type of place that attracted the cyclists on Sunday afternoon jaunts. Michael Susi has a postcard view of the Unter den Linden on page 72 of his Upper West Side book. By 1919, however, the Real Estate Record and Guide is reporting the sale of this corner where a 16-story apartment-hotel still stands today. German and Austrian influence on the neighborhood is also reflected in this photo of Broadway at 104th Street, showing “Old Vienna” and “New Vienna” restaurants. This food was one of the first ethnic cuisines adopted by Americans, which eventually stretched from hot dogs to coffee cake and strudels, and to potato salad. In these early 20th century restaurants, no doubt there was Wiener schnitzel and apfelstrudel on the menu. Another type of early 20th century restaurant is the tea room, a place where women could find light refreshment, either alone or together. Hard to imagine now, but “proper women” could not appear in a restaurant alone, or even with a female friend, in the early years of the 20th century. Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s daughter, Harriot Blatch, sued the Hoffman House in 1907 for refusing to seat a friend and herself. She lost her suit in 1909, and even an attempt by the New York State legislature to end this discrimination failed. Finally, restaurant owners recognized that a new generation of women—more independent, educated, and earning an income —should be accommodated, and they became acceptable customers. But for years, a woman dining alone was advised to “bring a book” lest anyone think she was there for a nefarious reason. To accommodate women, department stores began to offer tea-room service. The Women’s Exchange Movement, established to help “gentlewomen” who had fallen on hard times, began to serve tea and light lunches at their locations, where women sold their hand-made items, like baby clothes, linens, and jam. The Schrafft’s restaurants, discussed below, grew out of this need to provide safe places for women diners. Here is a tea room in our neighborhood in 1935, on Broadway, between 105th and 106th Streets. Restaurants developed in many of the apartment-hotels that became residential choices on the West Side. The Clendening Hotel, at Amsterdam Avenue and 103rd Street, the Marseilles at Broadway and 103rd Street, the St. George at 102nd Street, and many others had dining rooms for their guests and other customers. In their advertisements, hotels offered the European Plan (accommodation, no food) or the American Plan (room rent with three meals). At the St. George, lunch was priced from 40 cents, and dinner from 60 cents. This one from the West End Hotel on 125th Street is typical of this type of restaurant. At both the northwest and southwest corners of 100th Street and Broadway there were—and still are—restaurants. The building that houses the Metro Diner today was established in 1871 as the Boulevard House; Peter Doelger bought it in 1894, adding to his line of saloons. For a while it became “Conroy’s”—my friend Rich Conroy discovered one of his ancestors had lived upstairs there, Irish-born John Conroy, with his wife and four children. The building has never been landmarked, but it has been altered, and steel-beamed, and it’s a miracle that it still exists. On the southwest corner, the two-story Carleton Terrace restaurant stood until, in 1923, the 15-story Carleton Terrace Hotel was built, and offered a roof-garden dining spot, another restaurant style of that era. Rooftop dining and dancing was popular in the hot summer days before air conditioning. Michael Susi includes a photo of the Carleton roof in his book on page 72. The Carleton Terrace later became the Whitehall Hotel. Another popular restaurant, Archambault’s, was at the southwest corner of Broadway and 102nd Street. The owner, F. A. Archambault, was the “proprietor” of the Hotel Belleclaire at 77th Street—also the site of a popular roof-garden restaurant. Archambault’s lasted for several years, gaining a newspaper mention in 1913 when Mrs. Strauss’ maid, “melancholic,” tried to jump from the fourth floor of the apartment building that housed the restaurant, bringing all the diners out to the street. Mrs. Strauss hung on to her maid, and she was rescued. In 1929, William Childs of the Childs-restaurant family bought the restaurant to develop a chain of restaurants patterned after foreign destinations, naming it “Old Algiers.” The opening of the IRT subway along Broadway in 1904 spurred the growth of the neighborhood. Early immigrants who had settled on the Lower East Side moved to the neighborhood, bringing what one writer called the Lower East Side’s “gift of the Jewish deli.” These food stores and restaurants soon became a popular feature. I could not find one north of 96th Street of the size and reputation of those stores at 86th Street and further south. The word “delicatessen” was of German origin, and meant a place that served and sold cured meats and sausages. Barney Greengrass, on Amsterdam at 86th Street, with both meat and fish offerings, was established in 1908, and is still there, as is Fine and Shapiro on 72nd Street. Artie’s at 83rd Street and Broadway is attempting a revival of this style. Of course the new residents brought the dairy restaurants too. Steinberg’s Dairy Restaurant was on Broadway’s east side between 81st and 82nd; their sign was recently uncovered when the Town Shop moved, causing neighborhood memories to reawaken. But just because I did not find a photo or a mention i An eating craze that began before the turn of the 20th century was an adaptation of authentic Chinese food: chop suey. I found an 1911 advertisement for a chop suey place in the Columbia neighborhood, and others may have existed on our Bloomingdale blocks. Much later, when Americans had been introduced to many other Chinese cuisines, our neighborhood became well-known for its Sichuan restaurants. Much has been written about fast-food dining getting its start in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Our neighborhood developed three restaurants operating in this mode. At first I wondered why the Automat and Schrafft’s chose their locations, since we are not a commercial neighborhood of offices and big department stores. However, we were an area with a dense population, and had lots of movie theaters between 96th and 110th Streets, including the Nemo, the Olympia, the Midtown, the Stoddard, the Riviera, and the Riverside. Pre- and post-theater dining spots were necessary. The Automat building on the southeast corner of Broadway and 104th Street is one of our neighborhood landmarks today. Built in 1930, it lasted until 1954. The popular Automats introduced “waiter-less dining,” standardized and predictable food items, and the added attraction of the mechanized offering of food when nickels were put in a slot. Joseph Horn and Frank Hardart brought the Swiss-invented, German-manufactured equipment to Philadelphia, and then branched out to New York City in 1912. When the last Automat closed in 1991 (on Third Avenue at 42nd Street) many nostalgic articles were written. Our Automat at 104th Street had the distinction of being the site of the mysterious deaths of two persons in 1934. A despondent man committed suicide by placing cyanide in a roll, and, after leaving it on a plate at a table to go to the men’s room, a neighborhood woman took the remains and also died. This story has become a cautionary tale, with the lesson of never, ever eating any leftovers in a restaurant. On the northeast corner of West 104th Street, the Broadway View Hotel was built in the 1920s, replacing the Metropolitan Tabernacle that had been located there. Lost in foreclosure in 1933, the hotel became the Regent, and a Riker’s took the corner store in 1947. This chain of what we would call a coffee shop today had locations all around Manhattan, and even had its own dishes, as pictured. One in Greenwich Village has been identified as the place Edward Hopper chose to make his famous painting “Nighthawks,” a work of art that has come to represent the loneliness of the large city. Our neighborhood Riker’s is best known for hiring ceramicist Michael Spivak to design swirling mosaic abstract murals for its corner columns, an artwork that has (miraculously!) partially lasted to today. The scaffolding currently around the building makes a good photo harder to take today, but here is a portion of the artwork. Our neighborhood Schrafft’s was located on the ground floor of the apartment building stretching from 107th to 108th Streets on the east side of Broadway, today the space occupied by the Garden of Eden. There was another one at Broadway and 82nd Street, where Barnes and Noble is now located. Schrafft’s began as a candy shop owned by a Bostonian, William G. Schrafft. Frank Shattuck owned a chain of the stores, and it was his sister who suggested providing light lunches for “ladies” and the idea took off, particularly in New York’s shopping districts where there were many lunching (and working) women who wanted a place to eat where they would be comfortable. The shops were a “retreat” from the bustle of the city, and served predictable comfort food, like creamed chicken and lobster Newburg, but also offered banana splits and ice cream sundaes, as the “special treat” that dining out could provide, and a place to bring a deserving child. All of them had candy counters ready to provide a take-home box of chocolates. They became cultural icons, with The New Yorker providing regular comical snippets “overheard at Schrafft’s.” Even W. H. Auden composed a poem in 1947 “In Schrafft’s.” Finally, there was a restaurant called Cecil at the Hotel Narraganset on Broadway at 93rd Street. Moving away from Broadway, just a couple of other dining spots in the Bloomingdale neighborhood include:

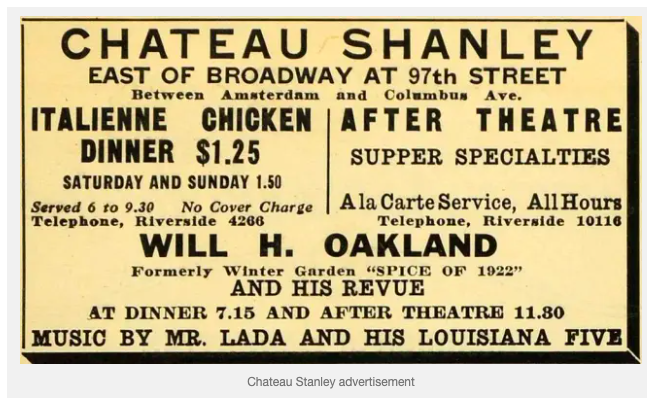

Chateau Stanley at 163 West 97th Street where PS 163 is located today. Before Chateau Stanley was located there in the 1920s, the space was Peter’s Italian Table D’Hote Restaurant in 1910, a place I was glad to find, as Italian dining was another “foreign” food that Americans adopted as restaurants developed early in the twentieth century. Michael Susi has photos of both in his postcard collection book, page 91. Sources

Michael V. Susi. The Upper West Side. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2009 James Trager. West of Fifth: The Rise and Fall of Manhattan’s West Side. New York: Atheneum, 1987 Peter Salwen. Upper West Side Story, A History and Guide. New York: Abbeville Press, 1989 Michael Lesy and Lisa Stoffer. Repast: Dining Out at the Dawn of the New American Century 1900-1910. New York: W.W. Norton, 2013 Michael and Ariane Batterberry. On The Town in New York. New York: Routledge, 1999 The New York Times archive The New Yorker archive Real Estate Record and Guide available online The Library of Congress newspaper archive, Chronicling America Website: www.restaurant-ingthroughhistory.com Digitized photo and map collections of the New York Public Library Digitized photo collection of The Museum of the City of New York Numerous sites found while Googling restaurant names.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |