|

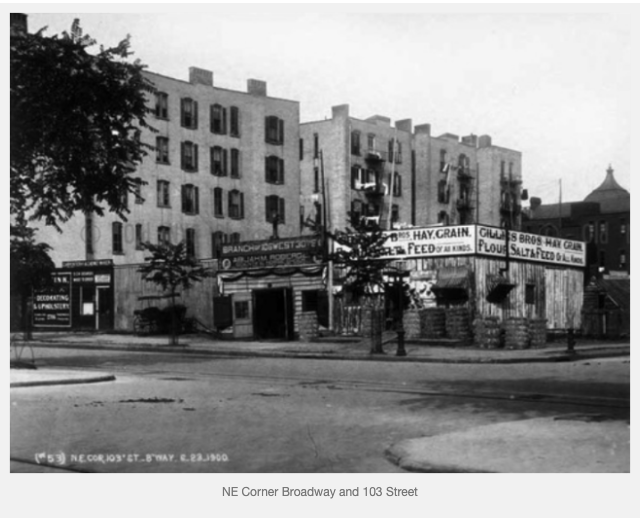

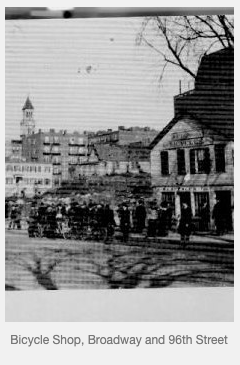

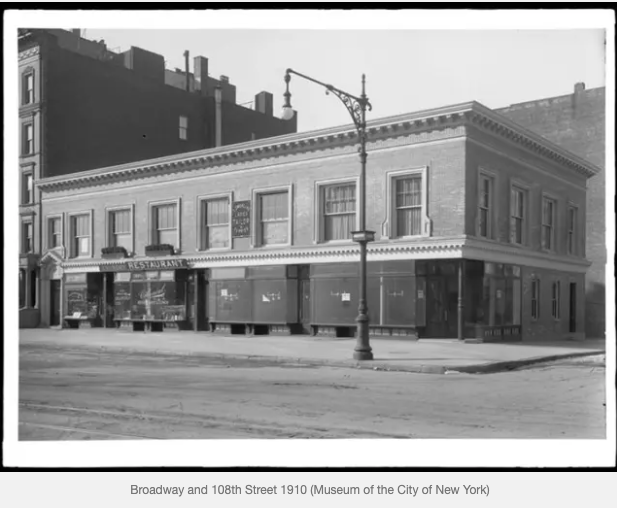

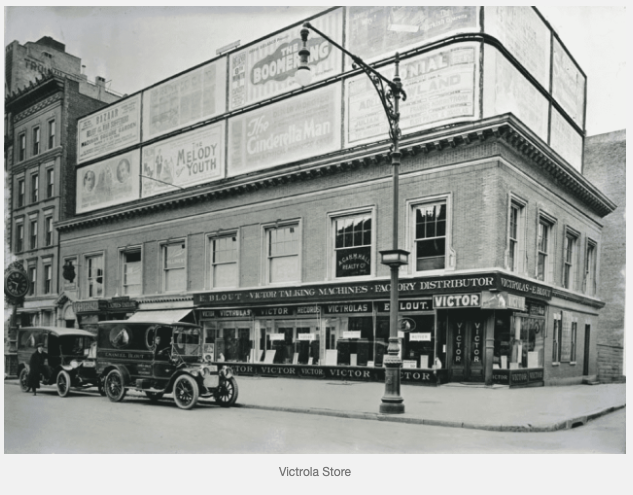

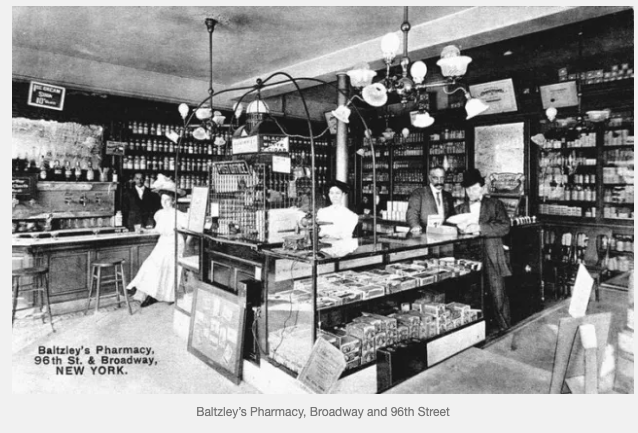

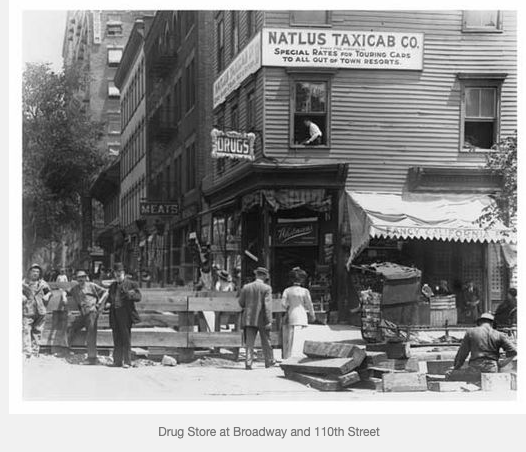

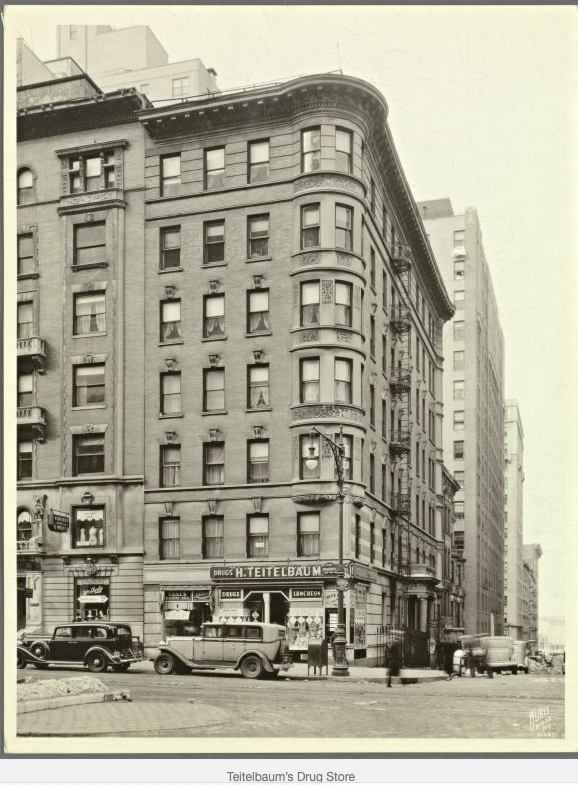

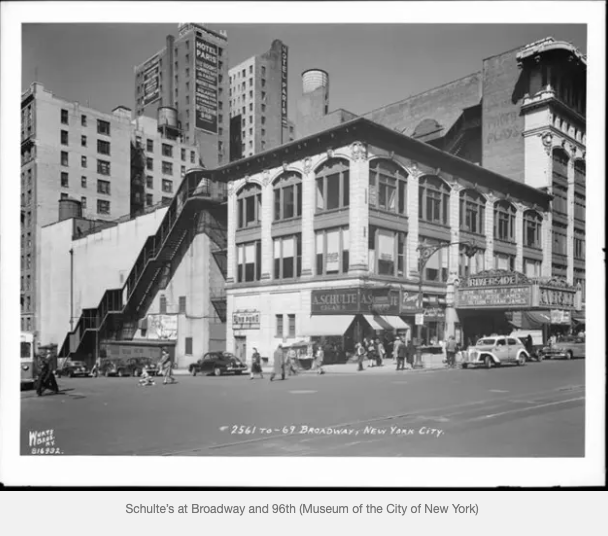

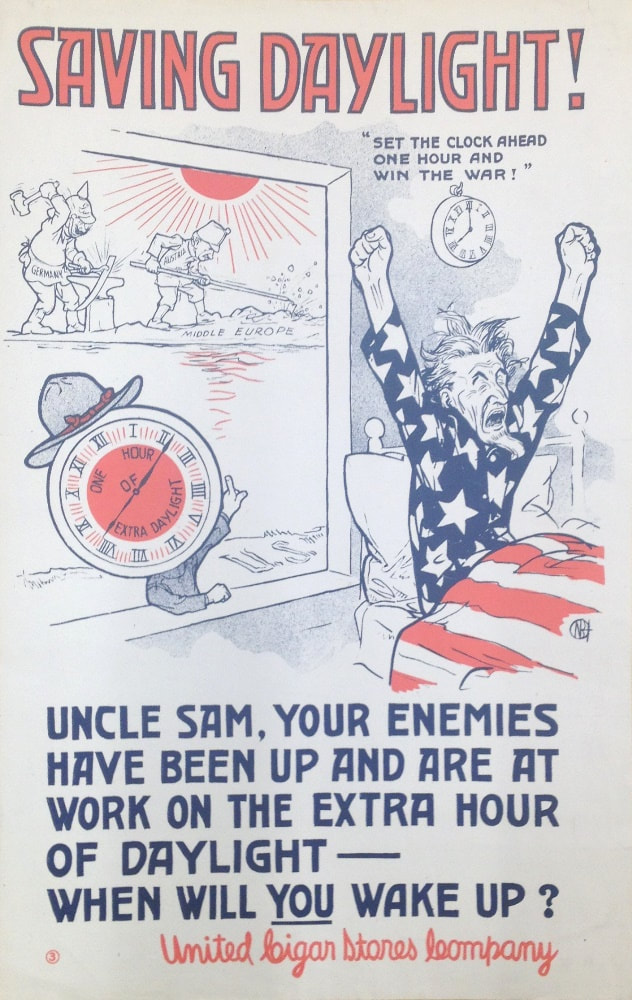

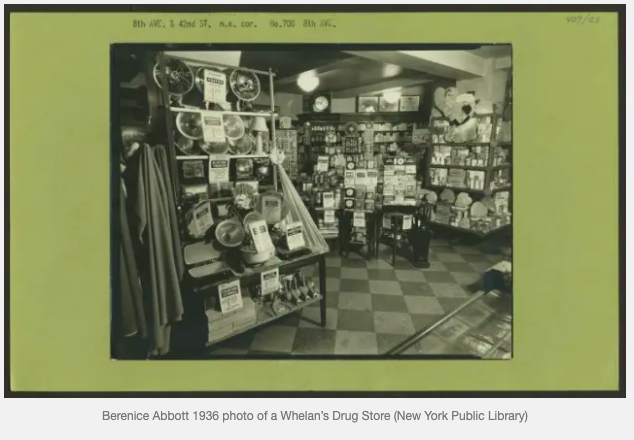

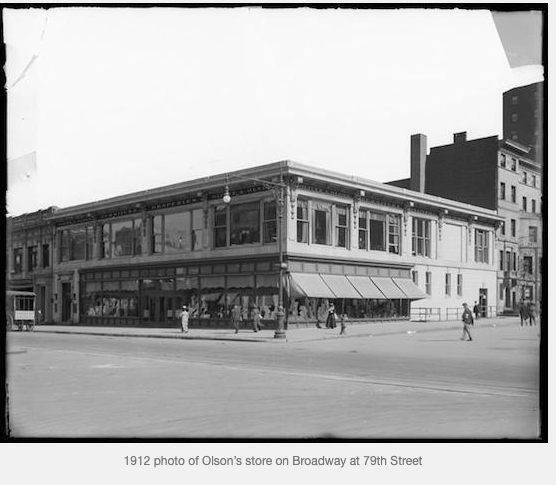

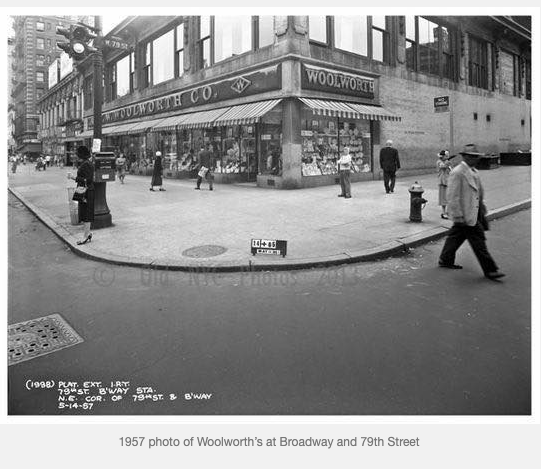

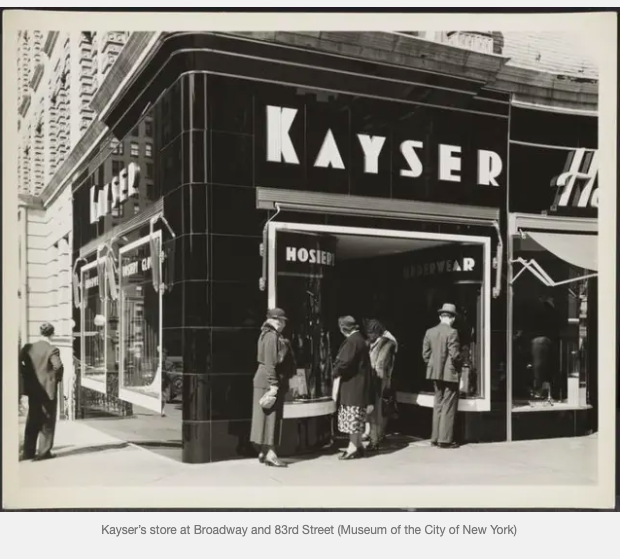

Here is another post on the Bloomingdale neighborhood of the Upper West Side. It was written by Pam Tice, member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group’s Planning Committee. A previous post about food provisioning in Bloomingdale described the streetscape of Columbus, Amsterdam and Broadway, a dynamic jumble of food suppliers: fruit and vegetables, bakeries, meats, seafood, delicatessens, and wine/liquor stores. From 1890 to 1940 while a few food suppliers became chain stores, most Bloomingdale neighborhood shops remained “mom and pop” operations. This post highlights a few of the other non-food shopkeepers providing goods and services for the neighborhood. With few exceptions, these also tended to be small shops: bootblacks early in the century, tailors, barbers, women’s hair salons, pharmacies, upholsterers, milliners, corset and flower shops. In the early years of the 20th century, the Upper West Side had an “Automobile Row” just above Columbus Circle where General Motors, Ford, Buick, Cadillac, Studebaker and Packard had display spaces. However, further uptown the stores tended to be small operations, each serving the neighborhood’s needs. Early on, there were numerous neighborhood bootblacks. One of them was Riddick Darden, who is listed in the 1900 Trow Directory. The 1900 census reveals that he was a black man, living in a rooming house on 99th Street. He appears to have been a neighborhood regular, as he is still there in the 1920 census listed as the owner of a “bootstand” at 99th street. Caitlin Hawke in her research of Bloomingdale neighborhood stores found this photo of Broadway’s northeast corner at 103rd Street, showing a shop selling feed and grain, demonstrating the country-like atmosphere of the turn-of-the-century Bloomingdale. The odd-shaped building on the horizon is the Home for the Destitute Blind constructed in 1886 but removed about thirty years later. Another early shop was W. G. Spencer’s Bicycle Shop housed in this wood-frame structure at Broadway and 96th Street, SE corner. This bike shop and others in the area served the cycling craze of the 1890s when cyclists pedaled their way uptown to the Claremont Inn on Riverside, just above Grant’s Tomb. Another Caitlin Hawke discovery: there was a store on Broadway at 108th Street, what we would today call a “destination” store: Emmanual Blout’s Victrola Store. Mr. Blout’s store replaced a group of stores shown in a photo (below) dated 1910, including a restaurant and a funeral parlor. The photo of the Blout store is undated; in both the 1912 and the 1923 Trow New York City Directories, the store is listed at 2799 Broadway. As the sign indicates, this store was distributing the machines and records of the Victor Talking Machines Company manufactured in Camden, New Jersey. Thomas Edison invented the phonograph in the 1877, and in the 1890s Emile Berliner fostered the transition from cylinders to flat discs, coining the term “gramophone.” Later, E. Johnson used Berliner’s work and founded Victor Talking Machines, making Victrolas and records, and developing a famous brand, with Nipper the dog pictured listening to “his master’s voice” coming from the horn on the machine. This website has the details of these wonderful machines that were ushering in a new age of communication: http://www.victor-victrola.com/. In the 1930s as the radio became popular, replacing the talking machines, RCA took over the company, forming RCA Victor. Mr. Blout was an investor in the Berliner Company, then in Canada. His store offered more than just machines and records. In 1920, a musical publication, The Musical Monitor, announced that a Miss Helen Colley would be using the talking machine to teach classes at the store in musical appreciation, nature study, English, and physical training, for “teachers, mother and children.” Another store selling machines, vacuum cleaners “hand and electric,” owned by a M. Loeb, is also listed in the Trow 1912 Directory, at 2789 Broadway. If you were a Bloomingdale resident needing coal or wood, it might be supplied by Weber, Bunke & Lange, at 96th Street and the North River (the Hudson’s name); their office was at 2546 Broadway. Pharmacies—and later drugstores—were numerous in the Bloomingdale neighborhood. One of the earliest photos of a pharmacy shows Baltzley’s, located at 96th and Broadway in the Wollaston that was built in 1900. The photo shows a large array of products, and this store had a Post Office operating there as well, although it may have just been a drop-off location. Mr. Albert B. Baltzley owned it, his daughter Elizabeth worked there as a cashier, while a Mr. Henry “Hank” Miller was the popular manager. In the early days of Bloomingdale, pharmacies custom-made the compounds according to a prescription written by a doctor. Despite the training provided by pharmacy schools, the mixture of these raw ingredients was subject to great variation, and doctors became unhappy with the process. In addition, there were many patent medicines sold in the early pharmacies that often contained alcohol, opium, morphine or cocaine. Regulating prescriptions and other medicines became part of the early 20th century movement to make both food and drugs safe, starting with the first drug laws in 1901. Eventually “drugs” became manufactured products sold to the pharmacies. Here’s another photo of a drugstore, this one at 110th and Broadway, taken when there was street work underway, perhaps part of the 1904 subway construction. (There’s a lot more to see here; a meat store, a fruit store, and a taxi company advertising their services to “out of town resorts”.) There was a Hegeman Drug Store on the corner of 101st Street and Broadway in 1909. There is no photo of this location, but an image in the Getty collection shows a Hegeman’s with a soda fountain in 1907. In 1909, a newspaper advertisement lists the Broadway location, in which the items for sale included perfumes, toilet dainties, bath room luxuries, candies, cigars, stationery, drugs, medicines, rubber goods, sick room supplies, syringes, water bottles, bandages, and “other drugstore products.” In 1914 Hegeman’s and another New York chain, Riker’s, combined to make a 105-store chain, the largest in the country. “Soda Fountains” evolved from an early pharmacy product: a drink of soda water at the store, to help settle a stomach. Soon someone discovered that a splash of sweet syrup could be added to the soda water, and then ice cream and other ingredients. The soda fountain was born, a standard feature of drugstores. It was also a lucrative new revenue source. The other large chain of drugstores was formed by Louis Liggett in Boston in 1903, and, by 1914, he had 52 stores. The 1922 advertisement mentioned below showed four Liggett stores in the neighborhood, on Broadway at 80th, 86th, 103rd, and 110th Streets. Liggett also formed a “retailer’s cooperative,” the United Drug Company, that became the Rexall line of stores. In a newspaper advertisement in 1922, a free tube of Listerine toothpaste was offered in numerous drugstore locations, including several in our neighborhood: Marcel at Broadway and 103rd; on Columbus there was Edward Ackerman at 740, Henry Buch at 661, C. J.W. Reed at 888, Richless Pharmacy at 775, Uran’s at 997, and Charles O’Connor at Columbus and 94th. Over on Amsterdam, there was Louis Klein at 876, Bedrick’s at 515, and S. Coden’s at 81st Street. Dorb Drug was at Broadway and 92nd Street, and William McDonald at 2781 Broadway. This photo, taken at Broadway and 91st Street, shows a Teitelbaum’s Drug Store. In October of 1908, The City Record listed places where men could register to vote in the 19th Assembly District which covered the Bloomingdale neighborhood. This listing gives a glimpse into the variety of stores serving the men of the neighborhood: tailor shops at 2669 Broadway and 870 and 906 Amsterdam; a cigar store at 2782 Broadway; barber shops at 203 West 104th and 948 Amsterdam. Much later, the Broadway Barbershop, owned by Mr. Demetriou, who took it over in the 1950s, would become a part of the collection of the Museum of the City of New York when it closed. Now, there a museum of New York City barbershops just opened in our neighborhood, at Columbus Avenue between 73rd and 74th Streets. In every neighborhood, the cigar store was ubiquitous. Initially there were United Cigar Stores and D. A. Schulte stores, one of those pictured here, next to the Riverside movie theater. There was another store at Broadway and 85th Street, as reported in a news story of a 1928 robbery. These large corporations were also able to put out public messages, like this United Cigar poster, issued during World War One, promoting daylight savings time. In the late 1920s, Schulte thought it a good idea to merge with the Huyler candy company that had started a chain of luncheonettes, thus combining the cigar counter with the quick-lunch spot. A.D. Schulte was also known for its coupons, collected by men at purchase and used by women to order housewares from their catalogue. In 1919, Schulte leased the corner of Broadway and 104, including two buildings on 104th Street, although which specific corner is unknown. Meanwhile, United Cigar had combined with the Whelan Drug stores, getting the cigar stand and the soda fountain combined too. The Depression hit these retailers hard, and resulted in United Cigars and Schulte merging. The stores labeled “5, 10, 25 cent stores” were another popular chain store in the early 20th century. F.W. Woolworth and S.H. Kress stores were the two largest in numbers of locations, and both were based in New York City, (but neither started there). By 1914, Woolworth’s had 774 stores including 40 stores in Canada and 40 in England. Woolworth’s was one of the first retailers to allow their customers to handle the merchandise before a purchase. The store made all prices either five or ten cents, until twenty-cent items were offered in 1932. In 1935 they discontinued these selling-price limits. Mr. Woolworth’s family made news as his daughter, Edna, Mrs. Franklyn Hutton, who lived at 2 West 80th Street, until she committed suicide in 1924. Her daughter, Barbara Hutton, then five years old, went to live with her grandfather at his Fifth Avenue mansion. She became “the poor little rich girl” at her 1932 debut that was an ostentatious display in the Great Depression. Unfortunately, this New Yorker led a troubled life, spending her fortune, creating scandals and working her way through seven marriages and divorces. Woolworth’s was on the Upper West Side in two locations: at 79th and Broadway in the 1930s, and also at 91st Street and Broadway. Much later, there was a Woolworth’s on Columbus in the retail space serving Park West Village. When Social Security began in 1936, Woolworth’s sold wallets containing a display-version Social Security Card, half the size of a real card with “specimen” written on it. Nevertheless, that fake-card number was used by over 5700 people by 1943. As late as 1977 the number was still in use! Woolworth’s ended in 2008 during the Recession. New York City still has its stunning 1910 Cass Gilbert “Cathedral of Commerce” in downtown Manhattan, converted to residential space not long ago. Advertising on top of certain buildings was part of the street scene; this photo (below) from the Museum of the City of New York shows Oliver A. Olson’s store with many billboards. Olson’s had been a “high class” specialty store for women in its time on the Upper West Side. This view is of a 1907 postcard. Olson’s was mentioned in a 1919 article about the formation of a Mutual Protective Association formed with a number of New York City department stores, to protect against shoplifters and pickpockets. This member list included many of the stores that have continued or disappeared over the years: Best & Company, Stern Brothers, Franklin Simon, Bloomingdale Brothers, Gimbel Brothers, Saks & Company, and Lord & Taylor. Oliver A. Olson’s went bankrupt during the Depression and their corner at 79th and Broadway was taken over by Woolworth’s.  All of these mentions show the variety of shops meeting the personal needs of the Bloomingdale residents. An important supplier was Kayser’s shown in the photo below in their 1937 Art Deco form with a new kind of black glass. This store was on Broadway at West 83rd Street. Julius Kayser founded his silk glove company in 1880, and, by 1911, it had grown to silk gloves, hosiery and underwear — and patent leather gloves also. After Mr. Kayser’s death in 1920 the company grew and lasted into the 1960s, absorbing numerous other companies that made these items.  Something we don’t see in the streetscape today: there was a gas station on Amsterdam Avenue at 90th Street, as shown in this 1936 photo. Another one-of-a-kind store was the Broadway Bird Store, located at 93rd Street, in the 1920s. The store sold canaries and parakeets, and also aquariums and fish, as well as dog supplies.

Another retailer on the Upper West Side was a woman named Polly Adler who had a lingerie shop at 2719 Broadway in the 1920s. The shop did not last for long. Polly’s real infamous talent was in the numerous brothels in apartments she established around town, many on the Upper West Side. She was arrested numerous times during the 1930s, and eventually left town for the west coast, writing a best seller in 1952, A House Is Not A Home, made into a not-too-good movie with Shelley Winters in 1964. SOURCES Federal censuses available at www.ancestry.com New York Public Library photographs database Trow’s Directories located at the New York Public Library and the New-York Historical Society Trager, James. New York Chronology. New York, Harper Collins, 2003 Susi, Michael. The Upper West Side. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2009 The New York Times archive West 102nd & 103rd Block Association Blog Library of Congress Chronicling America newspapers database Real Estate Record & Guide online Museum of the City of New York photographs database.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |