|

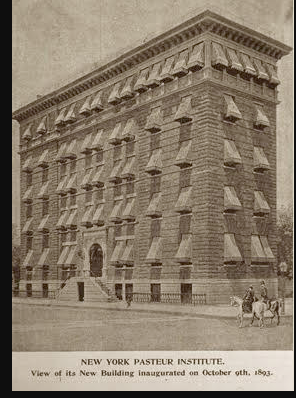

This is the third in a series of posts about buildings no longer standing in the Bloomingdale neighborhood; it was also the subject of an October 5, 2015, BNHG presentation by medical historian Bert Hansen, Professor at Baruch College, part of the BNHG’s series on medical institutions in our neighborhood. Dr. Hansen’s book is listed in the “Sources” section below. The book received awards by the American Library Association and by the Popular Culture Association/American Culture Association. Our thanks to Dr. Hansen for reading our draft and suggesting changes. Written by Pam Tice, member of the BNHG Planning Committee The New York Pasteur Institute on Central Park West at 97th Street Until the late 19th century, a dog bite was one of the most fearful things that could happen to you. If the dog were rabid, and you showed symptoms, you were sure to die a painful death. An infectious disease in mammals, rabies (lyssavirus) is transmitted through the saliva just a few days before death when the animal “sheds” the virus. Because it affects the central nervous system, most rabid animals behave abnormally. The disease still exists in the United States today, especially in the northeast in raccoons, but most dogs today are vaccinated. Humans, if thought exposed, can get a treatment far easier than the one first devised. People bitten by a rabid dog develop a disease that came to be called hydrophobia, a name used interchangeably with rabies. First displayed in humans as agitation, fever, and restlessness, it soon causes delirium, and then the inability to swallow liquids (hence the name), as even the smallest amount causes painful spasms and gagging. Most people died within a few weeks of contracting the disease. Before vaccinations, an outbreak of rabies among dogs or cats would often bring about a panic calling for all the animals to be destroyed. Until registration of animals became the norm, wild or unmarked dogs would be hunted and killed. That job often fell to a local police officer. The disease was so frightening that humans developed folk-type cures to treat it, including “madstones” which were placed on the wound and thought to soak-up the blood and poisons. Madstones were porous concretions found in the stomachs of deer. When Louis Pasteur announced in 1885 that he had cured rabies with a treatment involving a series of injections, the news was met with immense excitement and brought great acclaim to Pasteur. By 1888, his Pasteur Institute had opened in Paris, where it still exists today as one of the world’s leading research facilities. In December 1885, newspapers covered a story of five little boys from Newark who were taken to Paris to be treated. The trip was covered in daily detail, and, thanks to their rambunctious nature and the news coverage, the kids became national celebrities, put “on display” in a number of cities. These news stories had a big impact on the public understanding of the new treatment. A Parisian doctor, Paul Gibier, came to New York in 1888, a stopover on a follow-up trip to Florida where he’d planned to continue research on yellow fever that he had commenced in Cuba in 1887. Dr. Gibier was very well trained in infectious diseases. He opened the New York Pasteur Institute with a clinic at 178 West 10th Street to offer treatment for hydrophobia. Dr. Gibier also seems to have been skilled in attracting funding. A “Wall Street” benefactor funded his new building, and he secured funding from New York State for the vaccination regime for indigents. His work was also regularly covered in the press, including special mention when the famous teacher of deaf mutes, Annie Sullivan, came to him for treatment. Dr. Gibier also organized the New York Bacteriological Society to pursue research in tuberculosis, tetanus, epilepsy, and other diseases. Dr. Gibier was featured in a New York Herald article in April 1889 titled “Among the Horrors, An Afternoon with the germs of Cholera, Yellow Fever, Smallpox, Consumption and Hydrophobia, the Kitchen of the Microbes.” The reporter visited his laboratory and reported in detail just what the doctor did, how the microscope worked, what a glass slide looked like, and the possibilities for solutions to these diseases that the “French savant” Dr. Gibier brought to light. Reading this article today — even with all we know about science and with contemporary education that includes time in a laboratory — one can still find admiration for Dr. Gibier’s work. We can also see the importance of science-news reporting as it educates the public about the solutions to once-frightening mysteries. By 1893 Dr. Gibier opened a five-story brick building at the corner of Central Park West and 97th Street, pictured here. Soon the Pasteur Institute was treating patients from all over the United States, and keeping its animals for research on the roof, and on a farm in Bayside, New York. As important as it was to start treatment immediately, it was also crucial to have the viral material— developed in rabbits’ brains —ready as needed. Over 14 or more days, the patients received increasingly strong injections. Dr. Gibier also admitted patients with epilepsy, since he was working on an injectable anti-toxin for that disease also, as reported in the press in 1893. In 1895 he announced an anti-toxin for lockjaw, what we call today the “tetanus shot.” Dr. Gibier was an oft-quoted figure in the press on subjects other than his research. He commented that the recently-discovered canals on Mars were clearly the work of intelligent beings. He published a book on “psychism” and investigated other aspects of spiritualism. Unlike what would happen today, his explorations in these areas did not bring any criticism.

Starting in 1895, Gibier expanded the Institute, purchasing a 200-acre estate in Suffern, New York, where he could both provide a sanitarium as well as barns for the horses, cows, and sheep he needed to produce the diphtheria and smallpox vaccines. The Institute on Central Park West closed, but maintained an office on West 23rd Street (in a house that famous actress Lilly Langtry had once rented) to evaluate bite victims. In 1900, Dr. Gibier was killed in a carriage accident while returning to New York from Suffern. George Gibier Rambaud, his nephew, succeeded his uncle, but sold off the Suffern facility, keeping the West 23rd facility for a while. Soon, hospitals were able to establish vaccination procedures, and a special facility was no longer needed. Rambaud was kept in the newspapers by an alleged affair and then a second marriage to a popular French contralto with the Metropolitan Opera. He became embroiled in a controversial treatment for tuberculosis with a turtle vaccine, in another facility known as the Friedmann Clinic at West End Avenue and 103rd Street. The Pasteur Institute closed in 1918, when Rambaud joined the Army to fight in World War I. The handsome brick building on West 97th Street that was the Pasteur Institute — which had been leased to Dr. Gibier — was sold to a T. Chambers Reid in 1893, shortly after it opened. In 1898, the owner was the “C.R. Cornell Estate” as the building was altered to become a hotel known as the Cornell Apartment Hotel. It is listed as such in the Brooklyn Eagle Almanac of 1906. It is unknown how long the building lasted. It appears on maps at least through the 1920s. Eventually, the lot became part of the Park West Village development of the 1960s, specifically, 372 Central Park West. Sources Chapters 3, 4, and 5 in Bert Hansen, Picturing Medical Progress from Pasteur to Polio: A History of Mass Media Images and Popular Attitudes in America (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press 2009). The Real Estate Record digital version at Columbia University Libraries Digital Collections Talk by Bert Hansen, Professor, Baruch College, presented by the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group, at Hostelling International, 891 Amsterdam Avenue, New York, October 5, 2015 Bromley and Sanborn Maps at New York Public Library The New York Times Archive New York Herald available through www.genealogybank.com.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |