|

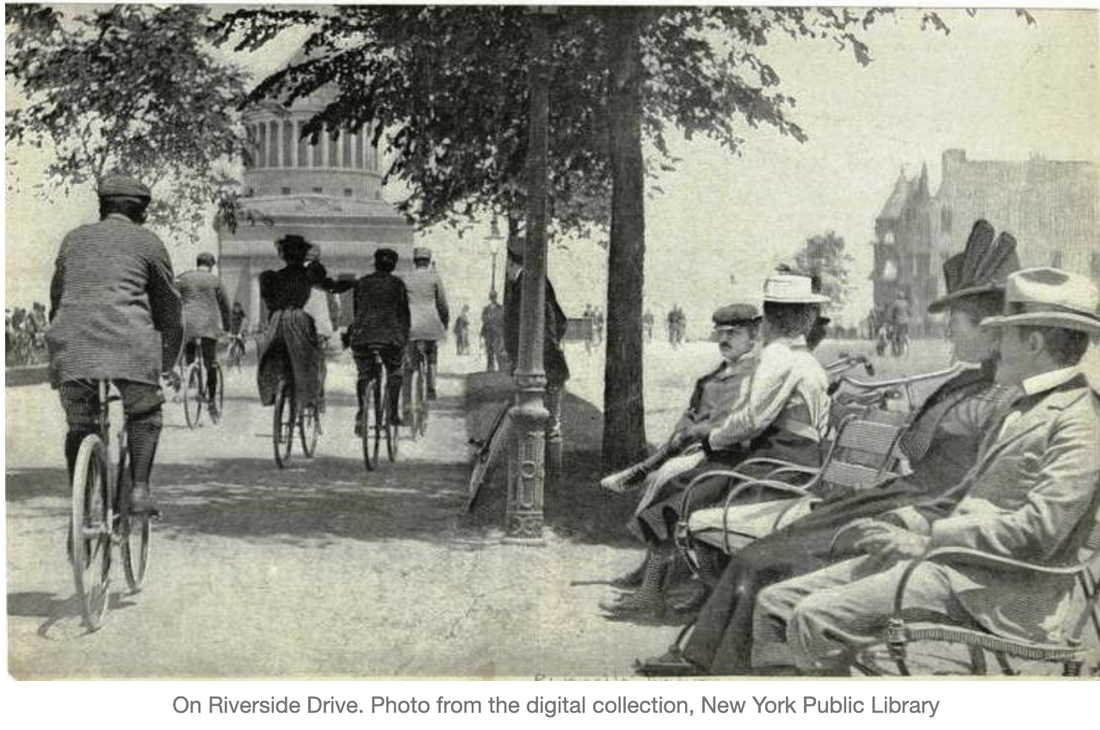

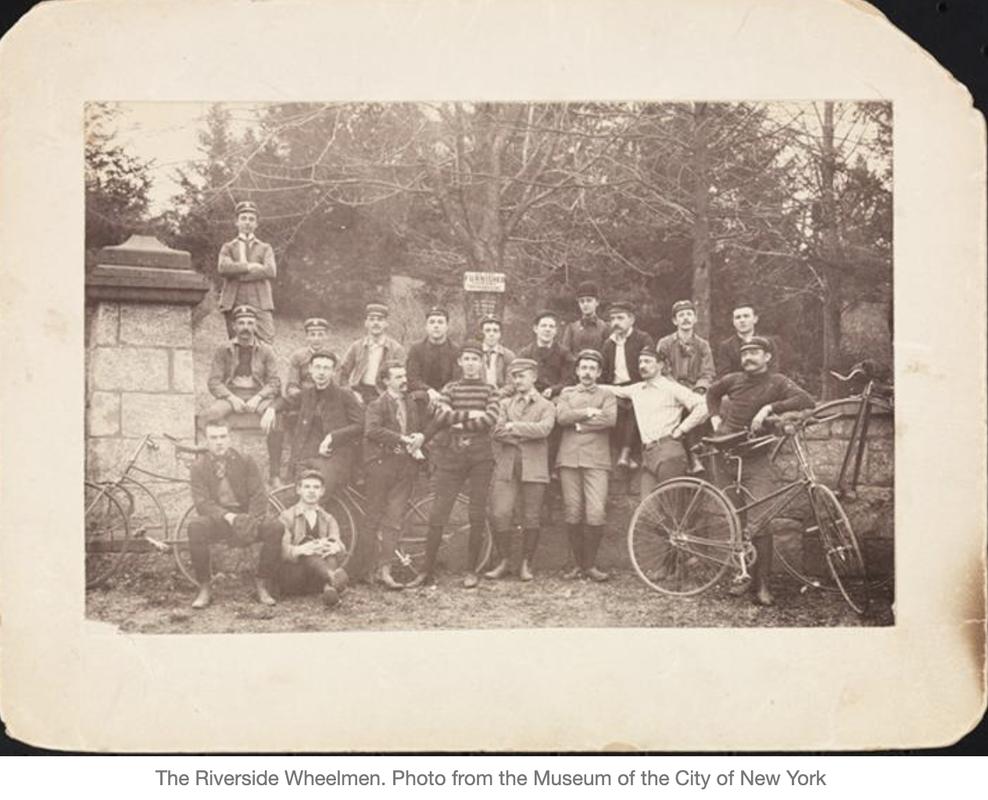

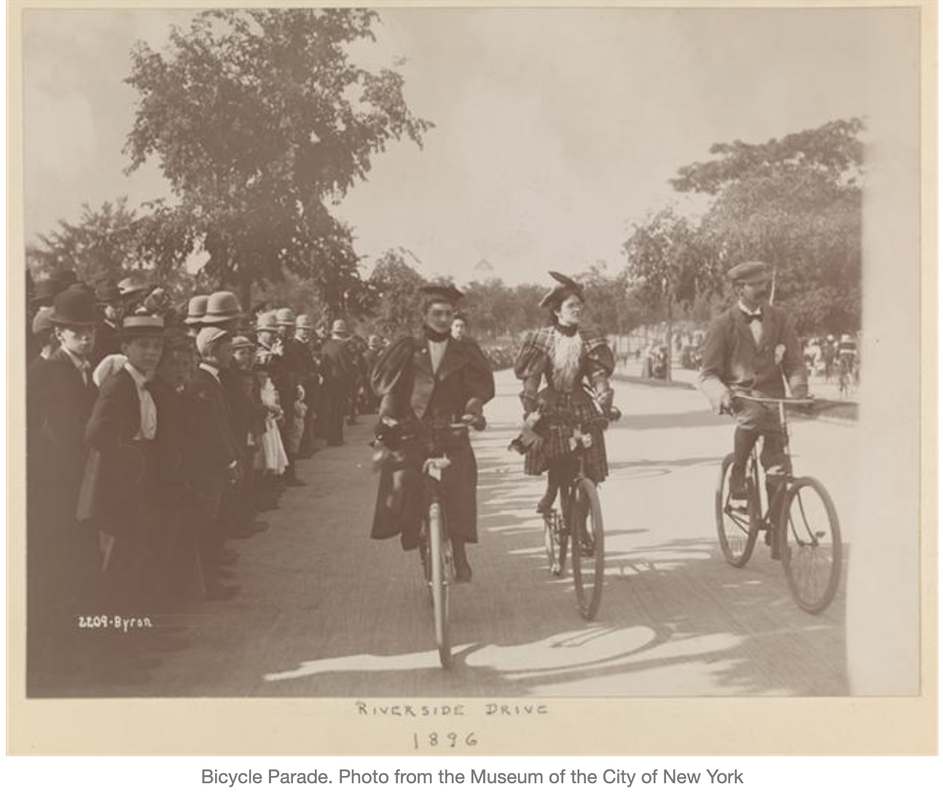

By Pam Tice, Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group Planning Committee In the 1890s, a bicycling craze swept America as men and women purchased bicycles and took to the roads. The safety bicycle, a machine much like the one we have today with equal-size wheels and inflated tires, fueled the craze as the model became widely available by the mid-1880s. Bicycles cost from $45 to $75, making the craze very much a middle-class phenomenon. In our Bloomingdale neighborhood, with its paved roadways and two parks, the bicycle craze became part of street life. Central Park West and Eighth Avenue was paved up to 135th Street by 1898, although riders found the darkened street under the El (above 110th Street) hard to maneuver. Central Park became popular for bicycling by the mid-1880s after Park rules allowed cyclists to ride on the drives, already busy with carriages and horses. The Boulevard, later named Broadway, was a popular bicycling route, from Columbus Circle up to Grant’s Tomb and the Claremont Inn. Certain parts of the new Riverside Drive also attracted wheelmen and wheelwomen, as the bicyclists were called. In the spring of 1896, traffic counters noted more than 14,000 bicyclists over a sixteen-hour period. Over the decade, more control over bicycles developed. Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt initiated bicycle policemen. Traffic rules were passed, recognizing the bicycle as a vehicle, ruling that it must stay to the right, carry a lantern at night, sound a bell when passing or turning, and travel at no more than eight miles an hour. The bicycle’s popularity spurred manufacturing from the bicycles themselves to the accessories needed, including clothing. Tailors and bootmakers were kept busy. There were many shops around the city, and riding academies, inside spaces, where novices could learn how to ride and how to maintain their wheels. Bicycle clubs were popular, at first just for men, and later including a few women. Eventually, there was a club exclusively for women. Even New York’s elite “400” had their exclusive club, the Michaux, by 1894. In Bloomingdale, the Riverside Wheelmen became one of the city’s most popular clubs. They purchased a brownstone house headquarters at 232 West 104th Street in 1889. As with all the clubs, the newspapers had regular columns reporting on bicycling activities. The wheelmen of the Riverside club had standard male social practices and club amenities, including a billiard room where contests were held, “smokers” and other social activities, like group singing, piano solos, and comic recitations. They sponsored dances at a location uptown. It’s unclear if they admitted women or just tolerated a few who had good riding skills. The Riverside Wheelmen organized their bicycling activities into two general categories: races and sponsored day rides. For amateur racing, the League of American Wheelmen established racing rules the clubs agreed to follow as members. If they allowed women to participate the event would be “unsanctioned.” The Riverside Wheelmen organized races at Manhattan Field at Eighth Avenue and 155th Street, a popular spot for college football and other sports events. At an annual July event, the Riverside Club presented a day of racing events of different challenges, attracting huge crowds. For non-racing members, the Riverside Wheelmen organized weekend day-long rides up to Westchester County, over to New Jersey, or through Brooklyn to the Rockaways where swimming was added. One of the first Captains of the Riverside Wheelmen was Franklin M. Cossitt. He married Caroline Gray in 1887; they are listed in an 1890 city directory at West 119th Street. “Carrie” joined him in his bicycling enthusiasm and in some news reports she is referred to as a member of the Riverside Wheelmen. She signed up for a century (100-mile) ride in Philadelphia in 1890 but the poor condition of the roads exhausted her and she could not finish, the only time she tried an event she could not complete. There is a photograph of Mrs. Cossitt in the collection of the Museum of the City of New York with a note on the back indicating that she was the first woman in New York City to use a safety bicycle. Because there were so many women learning to ride at this time, the statement is discounted today. The Cossitts moved to New Jersey by the mid-1890s and continued their bicycling there. Another woman who was sometimes referred to as a Riverside Wheelmen member was Nellie Benson. She lived on West 65th Street and rode tandem with Fred Lester who lived at the same address, although she was always referred to with a “Miss” before her name. In 1897, Fred and Nellie rode from City Hall in New York to City Hall in Philadelphia with Nellie in front. In 1896, Fred and Nellie were arrested for “scorching” (riding fast) on the Boulevard; when they were brought into court, the judge found that he could not fine “a lady” and so Fred had to pay the $3 penalty twice. In 1891, the actor James Powers applied for membership in the Riverside Wheelmen, an announcement that also noted that many artists and writers were attracted to that club. Powers was a comedic actor and singer of some renown, living with his wife at the Ansonia. His papers are at the New-York Historical Society today. Religious leaders across the country expressed concern about the bicycle craze and its tendency to keep young people from church on Sunday. Church attendance by men had already fallen off, and now ministers worried that women would stop attending Sunday services. The Reverend John Peters of Bloomingdale’s St. Michael’s Episcopal Church (Tenth Avenue at West 99th Street) had an idea. In June of 1896, he arranged for the church to set up a “bicycle check-in,” and encouraged people to attend the 7:30 am service before setting off for their Sunday ride. His wife, in a New York Times interview, expressed sympathy for working people whose only day off was Sunday, and how late-morning services interfered with having the whole day for restorative recreation. The Church placed a sign in the drugstore a block away at the corner of the Boulevard and planned further signage to attract the bicyclists riding uptown to stop by the church for the early service. The city’s bicycle clubs all had uniforms, so when they rode together, they would be recognized. By mid-decade, bicycle parades were popular. A June 1896 event sponsored by the Evening Telegram, brought crowds to the westside. Costumed riders headed uptown on the Boulevard at West 66th Street, riding up to West 108th Street, crossing over to Riverside Drive, then up to Claremont Avenue, and back downtown. Riders were given awards for having the most grace, best costume, and best club. One of the lasting legacies of the bicycle craze was the effect it had on women and how it contributed to their liberation. The criticism of women was tremendous, ranging from the effect of mounting a machine that might lead to sexual arousal, to predicting her inability to have children. Some said her hands would become enlarged, another loss of femininity and feeding the fear that women would become more like men. The social norms which constricted women from meeting men only under the supervision of their parents were also challenged. Out of all of this change came the turn-of-the-century’s New Women.

Those in favor of bicycling for women presented the healthy outcomes that would result: the improvement of muscles and overall well-being, the opportunity to explore the world and learn about history and geography, and the freedom to move around without having to ask someone’s help. Susan B. Anthony said, “I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel …the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.” One of the most popular topics in the press about wheelwomen involved the proper clothing. Bloomers had a mixed history from an earlier attempt to make women’s clothing more rational. During the bicycle craze, the city’s tailors worked to develop comfortable and riding costumes. The choice that became the most acceptable was knickers with a shorter skirt over them, stockings, ankle boots, a short jacket, and a not-too-big hat. Some women, like century-rider Nellie Benson, wore just knickerbockers with no skirt. Marie Ward, of the Ward’s Island New York family, known as “Violet,” included all of the best clothing choices in her popular book Bicycling for Ladies. Her Staten Island friend, Alice Austin, did the photography. Ward included information on bicycle repair and the tools needed, reminding women that they used needles and scissors and could easily adapt to bicycle tools. Ward’s bicycle shop was on Staten Island. One measure of the ending of the bicycle craze was the fall-off in League of American Wheelmen membership from over 100,000 in 1898 to just 8,600 in 1902. The craze was over. Bicycling returned somewhat during the Depression but by the 1940s and 1950s bicycles were considered children’s toys. Sources Newspaper database at newspapers.com Ancestry.com Ebert, Anne-Katrin “Liberating Technologies? Of Bicycles, Balance and ‘The New Woman’ in the 1890s” Icon, Vol 16. Special Issue (2010) pp.-52 MacPike, Loralee “The New Woman, Childbearing, and the Reconstruction of Gender, 1880-1900 NWSA Journal, Vol 1, No. 3 (Spring 1989) pp368-397 Taylor, Michael “Rapid Transit to Salvation: American Protestant and the Bicycle in the Era of the Cycling Craze” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, Volume 9, No. 3 (July 2010) pp. 337-363.

1 Comment

William Porto

4/6/2024 08:28:36 am

Fantastic article. Is there any data on cyclist injuries during those pre-helmet days? One imagines that the initial controls and brakes, plus road conditions would have lead to many cyclists crashing.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |