|

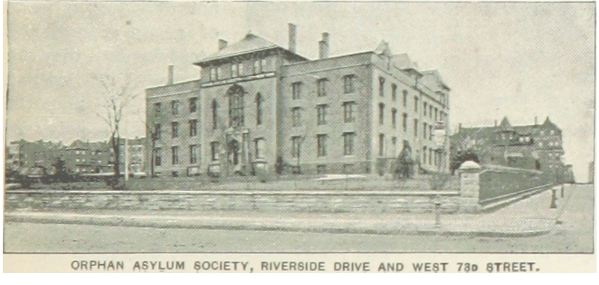

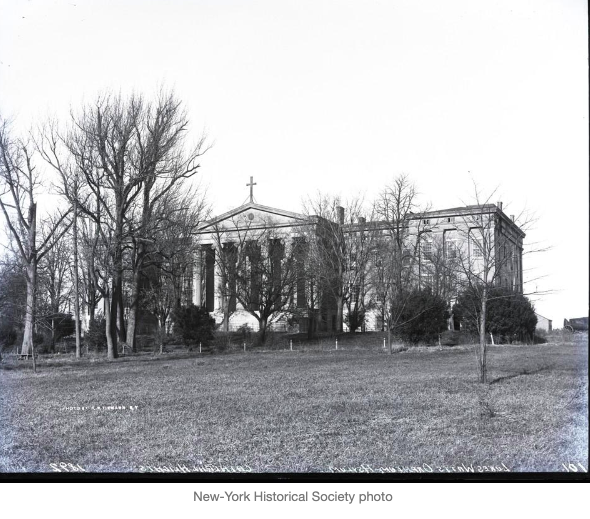

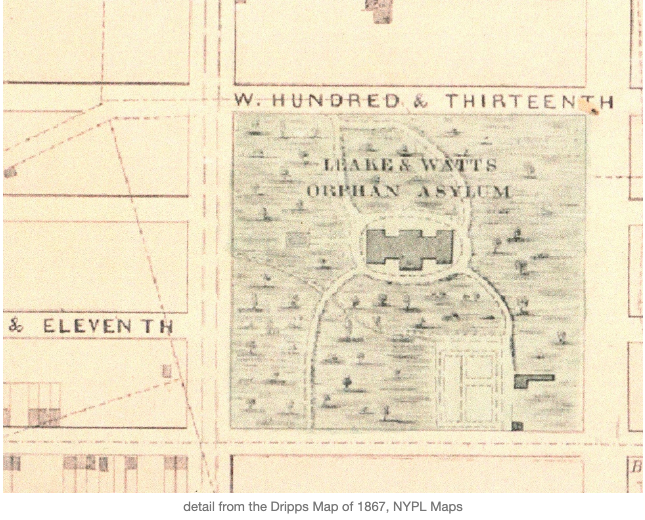

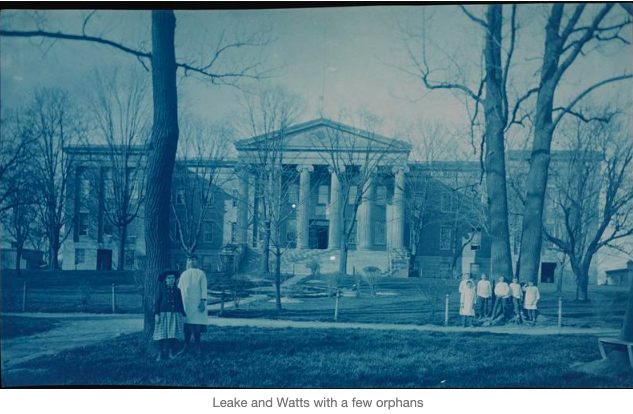

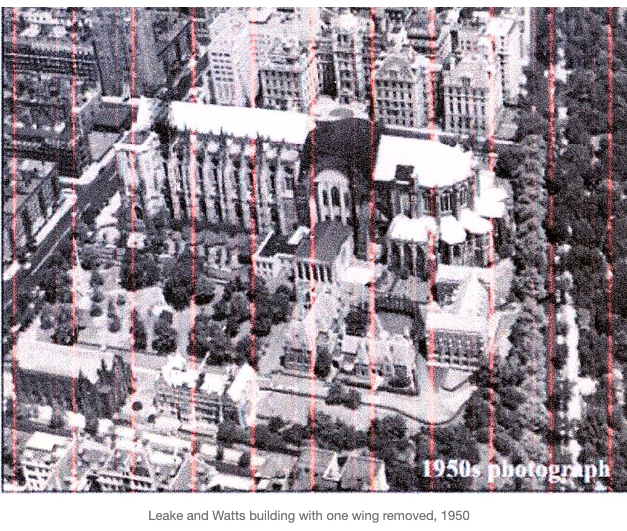

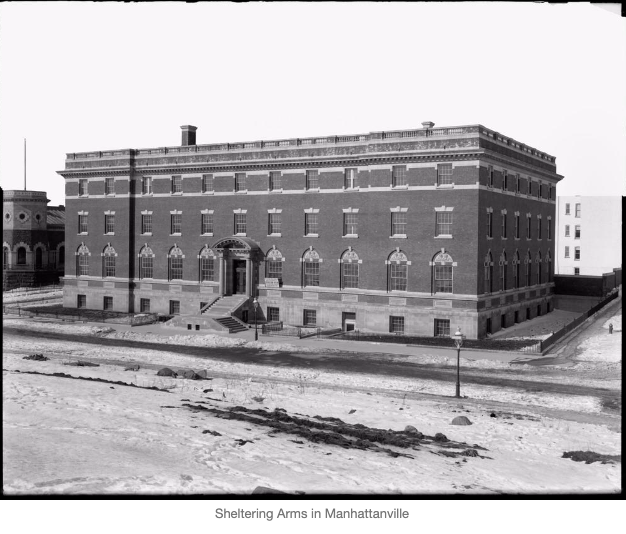

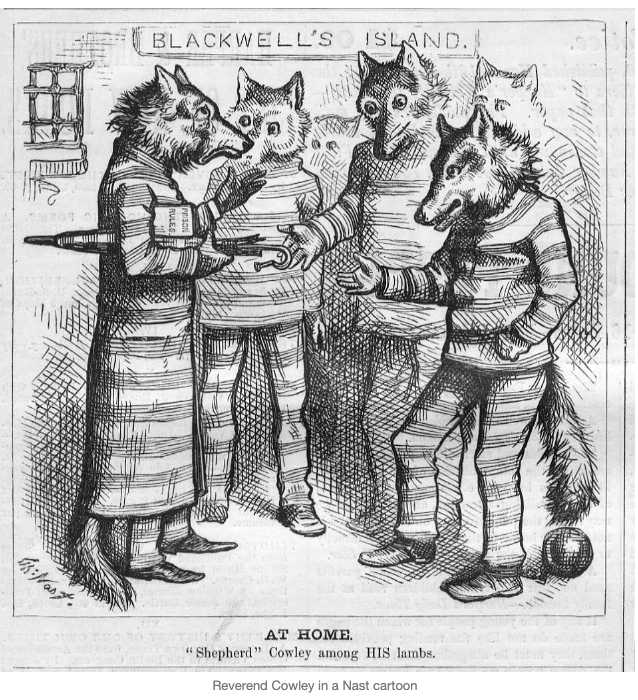

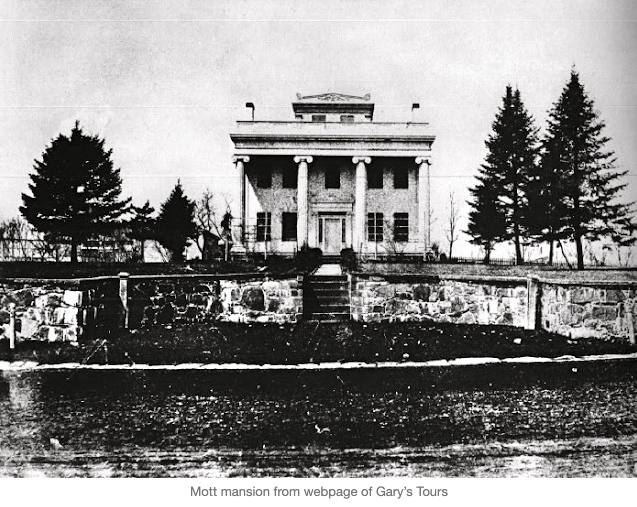

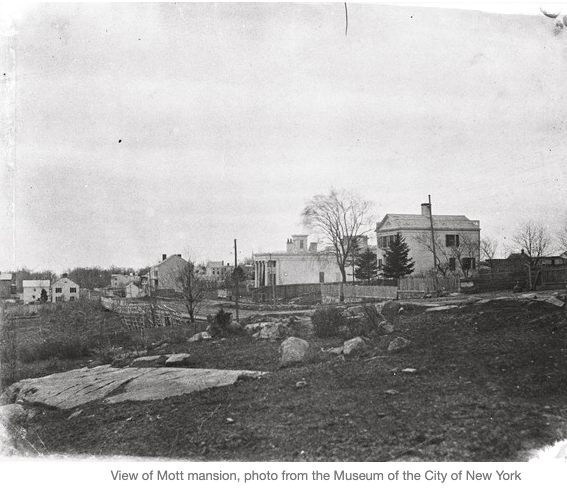

by Pam Tice, member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group Planning Committee The Upper West Side, a suburb in the early to mid-19th century, provided an excellent location for an orphanage. Land was cheap, the neighborhood’s country-like setting provided the fresh air children needed, and there was even space to grow food. New York’s increasing immigration in the 19th century expanded both poverty and disease in the city, leaving many parents unable to cope with caring for their children. The children of the poor who were left to fend for themselves were viewed by the City’s reformers as a threat to civic stability. In his 1872 book about the city’s many benevolent institutions, the Reverend J. F. Richmond wrote: “Every great city contains a large floating population, whose indolence, prodigality, and intemperance are proverbial, culminating in great domestic and social evil. From these discordant circles spring an army of neglected or ill-trained children, devoted to vagrancy and crime, who early find their way into the almshouse or prison, and continue a life-long burden upon the community.” A Police Chief called them “vagrant, vicious and idle children.” The descriptive language used reflected the general outlook of New Yorkers toward the thousands of immigrants who came to the New York City in the 19th century and the moralistic tone of the Victorian age. Religious institutions became the caretakers for many of these orphaned children. Starting in 1850, Catholic children were cared for in orphanages on Fifth Avenue and Madison Avenue in mid-town, and later moved to the Bronx. In 1860 the Hebrew Orphan Asylum was founded at Amsterdam Avenue at 137th Street. In 1837, the Colored Children’s Orphanage was built at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street. This one became famous when it was burned during the draft riots of 1863. It moved to Amsterdam Avenue and 143 Street, and later to Riverdale. South of our Bloomingdale neighborhood was the New York Orphan Asylum Society, organized by Isabella Graham in 1806. Initially, the group had an asylum in Greenwich Village. Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, recently widowed, was an early supporter. By 1839, the Society relocated to a large facility at Riverside Drive at 73rd Street where they stayed until the end of the 19th Century. The organization re-located to Hastings-on-Hudson where they are still in operation today as Graham Windham. Their property on Riverside Drive was purchased by Charles Schwab, who built his French Chateau on the site This blog post will focus on four orphanages located in and near our Bloomingdale neighborhood: the Leake and Watts Orphan House, the New York Society for the Relief of Half Orphans and Destitute Children, Sheltering Arms, and the Children’s Fold. The Leake and Watts Orphan House The Leake and Watts Orphan House was on the grounds of today’s Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine at 110-112th Streets and Amsterdam Avenue. A portion of the Orphan House is still there. The Leake and Watts Orphan House was created through the will of John G. Leake, a Scottish New Yorker of considerable wealth with a strong philanthropic inclination. Mr. Leake had no children so he decided to leave his fortune to Robert Watts, the son of his friend John Watts, if Robert would change his name to Leake. If Robert did not agree to the plan, the legacy would be used to erect and endow a building in the suburbs of New York City for the reception, maintenance and education of orphan children, with no regard to the religion of their parents, until the children reached an age to be put out as apprentices to trades. Robert did agree to the name change but died unexpectedly in 1829, and his father inherited his estate. Watts did not need another fortune, so he carried out the plan to build the orphanage, and named it after both of its benefactors. The Leake and Watts board was formed in 1832, with representatives of the Protestant Episcopal, Presbyterian, and Reformed Dutch churches. In 1834, nearly 25 acres of land from 109 to 113th Streets between Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues was purchased from the New York Hospital, which had excess land from the development in 1821 of the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum grounds to the north and west. The Board hired Ithiel Town, a prestigious architect, to design the Greek Revival building, a portion of which still stands today on the Close of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. The cornerstone was laid in 1838, and the Asylum opened in 1843. The Orphan House was built to accommodate 300 children but the endowment income that supported the operation was never sufficient for that number. Children admitted were between three and twelve years old. There were about 200 children listed there in the 1850 federal census, but only about 140 in the 1880 census. An 1882 news article stated that, since its opening, the orphanage had cared for 1000 boys and 500 girls. Girls were not admitted until 1850. The orphanage’s main entrance was from 110th Street, where a path led a visitor through a grove of trees. Descriptions of the site also mention a “fine lawn” extending from Ninth to Tenth Avenues. The Trustees owned other small pieces of land in the area, but these were sold off over the years as Morningside Park and the Ninth Avenue Elevated were built. The four-story building had two wings: the eastern for boys and the western for girls. Their space included a chapel, a dining room, wash rooms and ironing rooms, two large playrooms, an office, a parlor for trustees and visitors, and rooms for the Superintendent who lived there with his family, as well as numerous other staff as listed in the censuses. There were classrooms, as the City’s Board of Education listed the site as one of its schools. Each story had a wide verandah with an outside stairway that was meant to be a fire escape. Later, there was a one-story building added that served as a kitchen and dining room. The occupations of the staff living there listed in the 1880 federal census provide a window into the operation of the orphanage. The Superintendent and his wife, the Matron, headed the team. In 1880 there was an Assistant Superintendent, three cooks, one waitress, two farmers, one Assistant Engineer, five seamstresses, one nurse, four laundresses, five teachers, and three servants. In the photos, the children are wearing smock-type clothing which must have been the uniform that kept five seamstresses busy. The Leake and Watts Orphan House was in the news from time to time throughout the 19th century. Most reports were positive about the happy children living there, and one reported a special occasion in 1847 when President James Polk visited the City. His carriage stopped by the site on his tour of New York City institutions and he addressed the cheering boys. On Sundays, Protestant Episcopal orphans were taken to St. Michael’s Church at 100th Street where church pews were set aside for them. Other churches also welcomed them at their Sunday services. In 1845, the Trustees of Leake and Watts received permission from the State Legislature to “bind out” children to farmers, factory owners, and artisans in New York in order to teach the orphans a trade, so that they could support themselves as they reached adulthood. In 1847, the right to bind out was extended to include other states. These indentures began at age 12 and lasted three years for girls and five years for boys. Allegedly, the Superintendent stayed in touch with the orphans through correspondence and occasional visits. The Kings Handbook described this process as “finding a Christian home for the orphans.” Leake and Watts Orphanage sold its land and buildings to the Episcopal Church in 1888 for $850,000 and moved to a 40-acre site in Yonkers in 1890. The Cathedral initially used the orphanage building for construction offices and housing for employees. In 1892 they converted a portion of the building to a chapel. They established their Choir School there in 1901. As the Cathedral and accessory buildings on the Close developed, the orphanage building began to be demolished. In 1949 the east wing came down to make a parking lot and a basketball court. For many years the building continued to be used but began to crumble. When I worked there in the 1990s, it housed the Cathedral’s Textile Conservation workspace and other functions. Because the orphanage building sits on what one day will be the Cathedral’s south transept, no one wanted to take on its preservation. However, in 2004, a restoration project began, and today the restored building is called the Town building in honor of its architect The Leake and Watts Orphanage later changed its name to “Edwin Gould Services for Children and Families” and later took the name “Rising Ground” in 2018. The Society for the Relief of Half-Orphans and Destitute Children The Society was founded in 1836 by Mrs. William A. Tomlinson, whose widowed servant who told her of her difficulties in caring for two young children while she worked to support them. Mrs. Tomlinson and her sympathetic friends initially found a basement accommodation in Whitehall Street that housed 20 children. To be admitted, one parent had to be dead, the child, age four to ten, had to be free of contagious disease, and the remaining parent had to pay 50 cents per week for board. By 1837, the organization was incorporated with corporate powers vested in a board of nine male trustees who handled property and bequests. The “internal and domestic” management was given to a female board of managers. The age of the children taken into care was raised to fourteen years when the trustees were given the right to bind them out, or return them to their parent. The institution moved to West Tenth Street and later to its own building on Sixth Avenue. The Society was Protestant, but not denominational. The Society relocated to 110 Manhattan Avenue at 104th Street in 1891. There are few mentions of the Society or its asylum in the newspapers of the time; nothing of note seems to have happened while they were located there. In 1910, the Society received a donation of a 178-acre farm in Windham, New York, which became a summer residence for children in care. Eventually, it became Windham Child Care, and then joined with the Graham Home for Children, and became Graham Windham in 1977. Sheltering Arms In 1864, Reverend Dr. Thomas M. Peters, the Rector of St. Michael’s Church on Amsterdam Avenue at 100th Street, formed Sheltering Arms to take charge of children during moments of family distress. Some of the children were half-orphans whose parent had to work, some had incurable illnesses, and others were true orphans, with no parents. Initially, Dr. Peters housed the children at his own home at 101st Street and the Boulevard, where he had purchased his large house and one and a half acres. (St. Michael’s history reports that Dr. Peters moved his own family up to 110th Street to the old “Whitlock mansion.”) In 1866, Sheltering Arms built a nearby annex building. Sheltering Arms children did not have to wear uniforms and were allowed to attend neighborhood public schools. Their parents did not have to surrender them to the institution. However, by 1868 when the Boulevard was fully developed as a roadway, the property was reduced by eminent domain, and was moved to Manhattanville, where a new building was constructed by 1870. This was the first to use the German “cottage system,” separating the children into smaller groups called “families.” In 1944, at a time when most orphanages were closing down, and foster care became recognized as a better way to care for children without parents, Sheltering Arms merged with another organization, creating Sheltering Arms Children’s Services, which is still located today on East 29th Street in Manhattan. New York City’s Parks Department acquired the uptown land and created Sheltering Arms Pool and Playground. When Sheltering Arms was operating under Dr. Peters’ care, several children had to be rescued from two other Episcopal church organizations, the Children’s Fold and the Shepherd’s Fold, both operated by the Reverend Edward Cowley. Cowley had started the two organizations with housing on Manhattan’s East Side, in order to accommodate children who were “orphans of unfortunates” who had died at City institutions on Ward’s, Blackwell’s, and Randall’s Islands. Cowley’s organizations were paid $2 per week per child by the city. It’s unclear from the news accounts of the Cowley scandal if he formed the organizations to get the funding or if he was just a poor manager, but after an investigation by the newly formed Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, Reverend Cowley was formally accused of starving one child, Louis Victor, and was sentenced to one year in prison and a $250 fine. Cowley’s trial was sensational and included many details of child care during the 19th century. It also caused positive change in the way New York State allowed individuals to incorporate organizations that care for children. Thomas Nast included Cowley in the cartoon pictured below and he became a character in a play with a mean-spirited orphan-master. However, the Episcopal Church never prosecuted him. Reverend Peters took over the two organizations in 1877, housing the abandoned children in Bloomingdale homes and at Sheltering Arms. The Children’s Fold One of the Bloomingdale homes the Reverend Peters was able to gain access to for housing the abandoned orphans of the Children’s Fold was the Valentine Mott mansion at the Boulevard (now Broadway) and 94th Street. Dr. Mott, a famous New York surgeon, lived in Gramercy Park but had a summer residence in Bloomingdale. The first mention of the orphanage in the Mott mansion is in a June 1878 edition of an Episcopal Church newspaper, The Churchman, where it was reported that “ice cream entertainment” was enjoyed at an annual festival of the home. The newspaper reported, “The building was formerly the Mott mansion, an old-fashioned but comfortable and very commodious residence with pleasant grounds attached, shaded by large trees.” There were 65 children there, with room for 70. The Matron, Mrs. Skinner, a widow with two children, is listed in the 1880 federal census. Her staff consisted of her adult daughter, five “servants,” and two errand-boys to handle the 65 children counted there. The New York Infant Asylum

For a short while in 1865-1866, thanks to the work of Mrs. Richmond, the wife of the third rector of St. Michael’s Church, the old Woodlawn Mansion at 106-107 Street near Broadway and West End Avenue became the New York Infant Asylum. Here, the staff cared for foundlings and abandoned children under two years old. The asylum also provided obstetrical care for unwed mothers, but only during her first pregnancy, as the Board decided that it was human to make one mistake, but immoral to make two. The Infant Asylum was incorporated into other institutions and its history today is part of the complex of New York Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Moving Children to the Country While not part of Bloomingdale history, one other method for dealing with the thousands of children who required care in the mid-19th century was to bind them out as apprentices on the many farms surrounding the New York area. Recently, a friend shared a 19th century family diary with me, that of a western Massachusetts farmer named Franklin Williams. He writes in 1855, “May 3 in morning 5 a.m., arrived in New York. Stayed at the Western Hotel. Run about all day to get a Boy to take home but did not suit myself.“ The following day, he found one that suited him. The ten-year old parent-less boy was named William Farrell. Mr. Williams mentions also that he visited Mr. Pease’s School, which provided the clue to where he got his boy. Mr. Pease was in charge of the Five Points House of Industry, another institution that had the legal right to bind out children as apprentices. Mr. Williams only mentions his boy William once more, in 1857 when he “acted bad,” running away from a job but returning home late in the day. Getting children out of the city was ramped up considerably when the “orphan trains” were invented. The Children’s Aid Society was formed in 1853 and soon developed a way of dealing with the uncared-for New York City children by shipping them to farm families in the Midwest. Between 1854 and 1930, 150,000 New York City children were so relocated. Not all of them were orphans; some were sent away by their parents who saw this as an opportunity. Unlike the indentured children, the biological parents could retain custody. In recent years, as more people become interested in their family history, the history of the orphan trains has gained much attention. Sources www.ancestry.com The Churchman Volume 37, page 650 June 15, 1878 Cook, Jeanne F. “A History of Placing Out: The Orphan Trains” Child Welfare Volume 74, No 1, January/February 1995 https://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2018/10/noble-remnants-leake-watts-orphan.html Dolkart, Andrew Morningside Heights: A History of Its Architecture & Development New York, Columbia University Press 1999 Franklin H. Williams Diary 1852-1891 published privately by the Williams Family 1975 Sunderland, Mass. https://www.graham-windham.org/ New-York Historical Society files 1885 New York City Charities Directory (accessed online July 12, 2022) www.newspapers.com Peters, John P. Annals of St. Michael’s 1807-1907 New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons 1907 Presa, Donald G. and Jay Shockley, “Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine and the Cathedral Close” Designation Report New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, February 21, 2017 Richmond, John Francis New York and Its Institutions 1609-1871 New York E.B. Treat 1872 (accessed in digital format 4/11/22 at googlebooks.com) Rivlin, Leanne G. and Lynne C. Manzo “Homeless Children in New York City: A View from the 19th Century” Children’s Environments Quarterly Volume 5, Number 1, Spring 1988. Smith, Catherine L. “Nineteenth-Century Orphan Asylums in New York City, A Tiered Migration North” paper written for Professor Dolkart’s class, April 14, 2020. Accessed online. The New York Times archive, online.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |