|

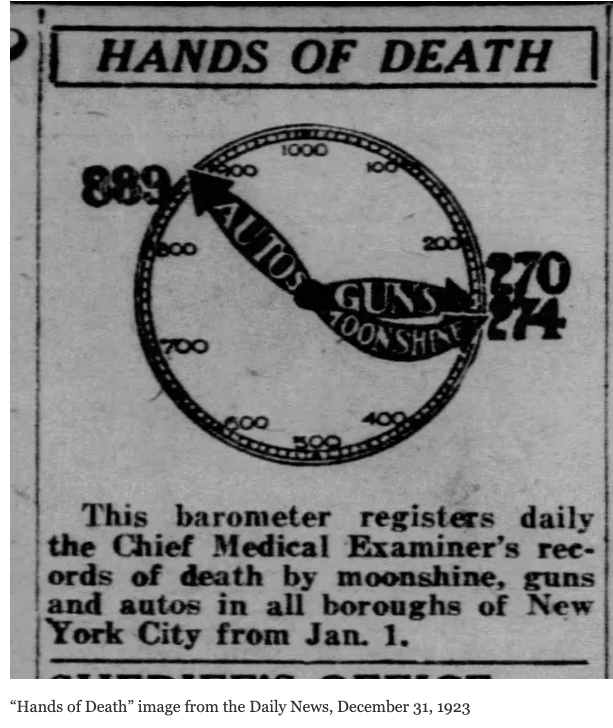

by Pam Tice, member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group Program Committee Scrolling through the 1923 Daily News articles about our Bloomingdale neighborhood, I was struck by the number of automobile accidents and deaths, as well as the arrests of drivers who lived here. The Upper West Side, of course, is famous for being the site of the first motor vehicle fatality in the United States, when Henry Bliss was killed as he got off a trolley car on Central Park West in 1899. In June, 1923, Mrs. Howland of West 95th Street was killed by an automobile while on her way home from St. Agnes Chapel on West 91st. Also in June, 13-year-old Theresa Bogert of 933 Columbus Ave. was killed at Riverside Drive and 108th Street while crossing with two young friends and a teacher. In the winter, a snowplow had killed a man on West 106th Street. Little Jimmie Walsh of Amsterdam Avenue was killed in April. Also in April, readers of the Daily News were reminded of the law that automobiles had to stay eight feet away from the area where trolley car passengers were discharged, with a reminder that two people had been killed recently at Columbus and 98th Street getting off the cars, a particularly dangerous location. The Parks Commissioner threatened to close Central Park to automobiles after dark due to the damage done to the Park’s plantings and structures. In June, an auto travelling at 50 miles per hour crashed into a lamppost at West 102 Street, killing the driver Bloomingdale neighbors also got their name in the news as they were charged in Manhattan Traffic Court: Michael McIntyre of 792 Columbus was sentenced to 15 days and had his license revoked for driving while intoxicated; Mr. Scaramellino of 813 Amsterdam spent two days in jail for turning corners too sharply; John McCourt of 832 Amsterdam spent 5 days in jail for speeding, and a cab driver living at 784 Amsterdam was assigned to the Work House for 60 days for driving while intoxicated. There were other incidents involving automobiles, whose drivers the News referred to as “autoists.” The word “car” was reserved for trolleys. Two autos with alleged bandits inside crashed at Riverside Drive and 97th Street. A young woman, screaming and clinging to the running board of a speeding auto that sped down Amsterdam from 86th to 66th Streets with 50 autos giving chase, ended up in an overturned auto and a bad injury. Just south of Bloomingdale, a speeding auto hit a crosstown bus, exploded its gas tank, and kept going as a ball of fire for several blocks since it was speeding at 40 miles per hour. What I was seeing in the news was the tremendous growth of automobile ownership in the 1920s, and the arrival of the American automobile age. The streets had to be turned over to automobiles. In January 1923, The New York Times reported on the opening of the national Auto Show, at the Grand Central Palace, where it was promised that 350 models made by 79 different manufacturers could be seen. The Times reported that 300,000 cars were now registered in New York City. But the streets in New York were not ready for this traffic. There were no painted lines, very few traffic lights, and a Police Department struggling to bring order to the streets. “Jaywalking” (an insult: walking like a “jay” or “rube”) was seen as a right by pedestrians, and children played in the streets, as not that many playgrounds had been built for them. Traffic lights were introduced starting in 1920, but the first ones, mounted on wooden towers at intersections, were only on one of the busiest streets, Fifth Avenue at the intersections of 14th, 26th, 34th, 42nd, 50th and 57th Streets. These were later replaced by bronze towers. The intersections in Bloomingdale might have had traffic policemen on some busy corners, perhaps helped by a manually-operated semaphore telling the driver to Stop or Go, a tool borrowed from the railroads that the Police Department adapted to auto traffic. According to the traffic rules printed in Rider’s New York City Guide for 1923, the speed limit in the city was 15 miles per hour, and 8 miles per hour at intersecting streets in congested areas. In more sparsely settled areas, the speed limit was 25 miles per hour. The slaughter of pedestrians by automobiles, including so many children, was happening all over the U.S., particularly in cities. The Daily News began to regularly report a disturbing picture of 1923 New York City. The Medical Examiner released the numbers of people killed by guns, autos, and “moonshine” which the News converted to little circular clock-chart labeled “the hands of death” several times during the year. The latest one in 1923, dated December 31, showed 889 people killed by automobiles on the streets of the city. The high number of auto deaths in 1923 was not new. In 1922, The New York Times reported that there had been 964 deaths by automobiles with 477 of them the deaths of children.

In 1923, several solutions were proposed or tried. The News reported that Mayor Hylan wanted to convert many of the trolley surface-lines to bus routes so that people could access the vehicle at the curb, not in the middle of the street where they might be hit by a careless driver. The Board of Education declared a “Safety Day,” late in the school year, trying to impress school children about the dangers of the streets. The schools also initiated a procedure at the end of the school day whereby the children would stand up just before dismissal and be reminded by their teacher for two minutes about the danger of playing or running into the street. Magistrates at the City’s Traffic Courts began imposing harsher sentences. The Police Department introduced new techniques with very loud whistles and initiated a system of checking auto brakes. The Daily News kept reporting on their “hands of death” from 1924 to 1933 when the charts disappeared. Legalized liquor had diminished moonshine in 1933. Perhaps death by automobiles and guns was never to be solved and just part of modern life. In 1931, auto deaths reached a high of 1448. Recent reports have noted the increasing number of traffic-related deaths in the U.S., many attributed to the number of SUVs and heavy trucks on the road, along with the distracted drivers who are focused on their phones. Indeed, in New York City in 1990 there were 701 traffic deaths. In 2014, New York City implemented “Vision Zero,” a Swedish program, a strategy to eliminate traffic fatalities. In our own neighborhood, at Broadway and 96th Street where there had been two pedestrian deaths, the traffic was re-routed. Even with this effort, through November 2022, 185 people were killed in automobile accidents, two in our neighborhood. Sources Newspaper databases at newspapers.com and The New York Times Websites: www.crashmapper.org and a history of traffic at https://local1182.org/about-us/history-of-traffic/ Norton, Peter Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City, Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press, 2008 Schmitt, Angie Right of Way: Race, Class and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America. Washington, D.C., Island Press, 2020. Posted in Uncategorized | 1 Comment

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |