|

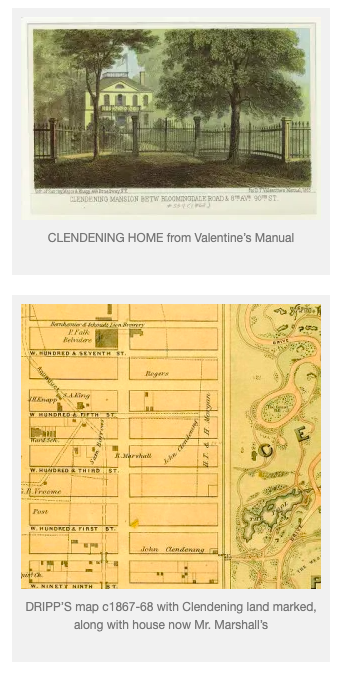

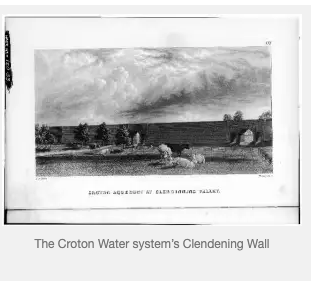

This is the second post of a series on Bloomingdale neighborhood places that no longer exist. It was written by Pam Tice, member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group Planning Committee. When John Randel made his 1818-1820 Farm Maps, he mapped a house on a Bloomingdale hill right in the middle at what would become 104th Street and Columbus/Ninth Avenue. This was the home of John Clendening, a wealthy New York merchant. After assembling the land in several transactions, he called his Bloomingdale farm “Sharon Farm.” Stokes’ Iconography of Manhattan Island includes notes on Clendening’s farm and how it came to be. John Clendening typified the wealthy merchants who purchased land in the Bloomingdale area on the west side of Manhattan, land that the Dutch had farmed as they settled Manhattan’s northern reaches. The original patent for the area in 1667 was granted to Isaac Bedloe, a New York Alderman. After he died in 1673, Bedloe’s land became divided through property transfers over the years, creating the Charles Ward Apthorp Farm, the Striker’s Bay Farm, the Herman LeRoy Farm, the John Clendening Farm, and a part of the Lawrence Kortwright Farm that became part of Central Park. According to Stokes, the block numbers assigned to the Clendening Farm are 1857, 1838, 1834, 1854, and 1857. Thus, if you are looking at Manhattan property on a map with block numbers, you can identify the area of Mr. Clendening’s estate. Clendening assembled his property by first buying ten acres in two pieces from land Herman LeRoy had sold to John Goodeve and James Brown in 1796. Goodeve became the sole owner at a later date, and in 1808, sold the acres to Clendening. In 1832, Clendening bought another piece of the LeRoy farm. But the most significant portion of his holdings came from an 1814 sale from a “Lawrence Benson, Gentleman, to John Clendening, Merchant.” Mr. Benson was the great-grandson of Lawrence Kortwright, mentioned above. The deeds to this property are measured in acres, roods, and perches. The terms “rood and perches” go back to the Romans and generally not used today, except in a couple of places that have deep English roots, including Jamaica (the Island). Stokes describes the area In 1819, and the “fine house fifty feet square standing 250 feet back from Clendening Lane,” the connection to the Bloomingdale Road, west of the Clendening Farm. Stokes describes the property as having “a driveway gate at the SW corner of 105th and Ninth Avenue, with the mansion just south of 104th Street.” Clendening Lane continued as a named place in the neighborhood for many years. Even as late as 1909, there was a property dispute involving the Lane, as reported in The New York Times. The Times story provides a detailed description of the Lane’s traverse: Clendening Lane branched off from Bloomingdale Road in the center of the 103-104 Block. (Bloomingdale Road ran between Amsterdam Avenue and Broadway.) At 100 feet east of Amsterdam, Clendening Lane headed northeast to 105th Street, to midway between Amsterdam and Columbus, then east to what is now Central Park. You can hover over a 1852 map of the Bloomingdale neighborhood and see the other property owners and the structures in place. On this map, the Clendening home has passed on to the next owner, Mr. Marshall, as discussed below. In the 1863 D. T. Valentine’s Manual, The New York of Yesterday, there is a picture of the Clendening home in 1863 indicating the wrong location, at West 90th Street and Eighth Avenue. Of course, this could be a home that was given the wrong name, but the mansion’s existence is also noted on the 1867 Dripps map as on the corner of Ninth Avenue and 104th Street – one author suggests that it might have been moved to fit onto the grid laid out by John Randel. It’s been difficult to find information about the Clendening family since no definitive family history seems to exist. Nevertheless, numerous facts are available in newspaper articles and old books. Before he moved to Bloomingdale — which one author called his “retirement” — Clendening lived downtown on Pearl Street, between Maiden Lane and Beekman Street. In those times, most merchants lived above their shops. Based on his age — reported with his death announcement — Clendening was born about 1752. While his age made him eligible for military service in the Revolution, I did not find any record of service. One report of his death indicated that he was born in Scotland. A note in The Old Merchants of New York indicates that he imported Irish linens. In 1809, he is listed as an Inspector for the election of the City’s “Charter Officers.” He is also listed as one of several men who made loans to the United States Government in 1813, when the government sought lenders to fund the War of 1812; Mr. Clendening loaned $20,000. In 1816, he was named a Director of the Second United States Bank, serving under John Jacob Astor, President. In 1825, he is listed as a Director of the New York Contributorship, one of many New York City fire insurance companies. John Clendening’s death was reported in The New York Gazette of January 29, 1836; his death had actually taken place two days earlier on January 27th. He was 84 years old. His funeral was at his residence, and the newspaper reported that “sleighs would be ready to take mourners to the funeral, leaving from St. Paul’s Church at half past eleven o’clock.” I have not been able to find his burial place; I’d thought he might have been interred in the St. Michael’s Church cemetery (later moved to Astoria), but did not find a record. However, not all St. Michael’s burials are listed. Thanks to just one genealogy on the Rootsweb site, I found a list of his children, but no definite note of his wife’s name. He had seven children — two sons and five daughters — all born in New York City. They are: James, born in 1791, who went into business as Clendening and Bulkley, importing Irish goods; Mary Ann, born in 1793, who died in 1807; John, born in 1795, reportedly remaining a bachelor; Margaret, born in 1797, who married Horace W. Bulkley, her brother’s business partner; Sally, born in 1799, who married William Hogan; and Jane, born in 1802, who married Mr. Kearny. The youngest daughter, Letitia, born in 1807, married Stuart Mollan, Jr. of Petersburg, Virginia. There is a newspaper mention of her marriage in 1836 at the Clendening estate, performed by the rector of St. Michael’s Church, the Reverend Doctor Richmond. Leticia and Stuart had a son, John Clendening Mollan, born in 1837. On February 3, 1838, a news announcement was made of the child’s death at ten months, 14 days old. That announcement uses “Sharon, in Bloomingdale” as the place of death, naming the farm. Leticia died in December, 1838 with no burial place mentioned. Stuart Mollan died on March 20, 1861, and is buried in Greenwood Cemetery. The John Clendening family is listed in the Federal censuses of 1790, 1800, 1810, 1820, 1830, and even 1840, after John Clendening’s death. In the earliest censuses, they are in downtown New York, in the “East Ward” and “Ward Three.” In 1810 and 1820, they are in “Ward Nine,” which is the lower west side, between Houston and 14th Streets. Starting in 1830, they are in Ward 12, which is the area north of 86th Street, the Bloomingdale “Village.” However, in 1850, the family “disappears” from the records. Perhaps that was due to the misfortune that occurred, described below. According to news reports, the reason for the sale of the Clendening estate was the family’s financial losses, sustained when the Second United States Bank failed. In the Stokes book, John Clendening’s will was dated July 1829, and was “proved” on February 21, 1836. He left the Sharon Farm to his wife, along with an annuity. The remainder was left to his children. The writer of The Old Merchants of New York — a somewhat chatty book that some say plays a bit loose with facts — reports that the children fought over the estate and then decided to invest in the Second United States Bank. Other reports say that John Clendening was one of the largest investors in the Bank, and this would have been an important part of the estate left to his family. Another diversion from the Clendenings: the Second U.S. Bank was chartered in 1816 based on the limited success of the First U. S. Bank that Alexander Hamilton had worked to establish, with it based on the Bank of England model. With all the renewed interest in Hamilton this summer of 2015 with a Broadway show, the subject of banking history doesn’t seem as dry and unimportant as it might have earlier. Andrew Jackson became President of the United States in 1828; he was extremely anti-U.S. Bank. In 1832, Congress passed a bill to renew the Charter of the Second Bank which was due to expire in 1836. The President vetoed the bill, based on his view of the Bank being unconstitutional (despite previous rulings by the Supreme Court that it wasn’t), and “subversive of the rights of States, and dangerous to the liberties of the people.” In February, 1836, the U.S. Bank became a private corporation under Pennsylvania Commonwealth law. A shortage of hard currency followed, causing the “Panic of 1837,” which lasted some seven years. The Bank suspended payments in 1839 and was liquidated in 1841. John Clendening’s death came just as the Bank’s charter was ending – although well before his death he knew it would cease. There’s no way of knowing of his efforts to save his fortune. In December 1844, an advertisement appeared in the Commercial Advertiser in New York that, by order of the Court of Chancery, the estate of the late John Clendening, seized, would be divided into separate parcels and sold. The ad describes the estate, in the 12th Ward, as being “on 8th and 9th Avenues, and on 99th, 100th, 101st, 102nd, 103rd, 104th and 105th Streets.” The auction was scheduled for the 15th of January, 1845, at Halliday and Jenkins, on Broad Street. The next mention of the Clendening estate is in a 1912 article in The New York Times about the “olde settlers” of the West Side. The article speaks with some wonderment of the value of the land as the Clendenning lots were sold off for between $9.50 and $55.00 each. The article states that the entire estate, including the house, only brought in $3,000. At the time of the article, in 1912, similar lots were bringing in $25,000. Robert Marshall bought the Clendening home and some of the land. In the Daytonian In New York blog, in a piece written about the founding of the West End Presbyterian Church (at Amsterdam and 105 Street), the congregation is described as meeting in the “Marshall Mansion.” A search through the federal censuses in 1850, 1860 and 1880 located a Marshall family. The parents, Robert and Ann, were both born in Scotland, an obvious tie to the Presbyterian Church. The children were Hannah, James, Ann, Robert and Margaret. In all the census documents, there are servants listed with the Marshall family, usually Irish-born young women. In 1860, there is a listed gardener, John Montgomery, which suggests that there were grounds to tend around the house. In the 1850 census, Robert Marshall is listed as a confectioner; in 1860 he is a “gentleman,” and in 1880, a “retired merchant.” A newspaper article in 1895 referred to him as a “real estate dealer,” and another article mentions the sale of a townhouse on West 88th Street that he owned. An 1891 newspaper article mentions a fire in a nearby stable (317 East 99 Street) “owned by Robert Marshall of 221 East 100 Street.” All the six “truck horses” died; four were owned by Marshall. The Marshalls appear to have been involved with the Fourth Presbyterian Church at West End Avenue and 91st Street in addition to the West End Church. After they died, their daughter Margaret honored them with a Tiffany window in the Fourth Presbyterian Church’s north transept. The window is still there, but the church is now owned by the Greek Orthodox Church of the Annunciation. The New York Tribune published an article in June 1897 about the Marshall Mansion, just after Ann Marshall died at 87 years, calling her home “one of the most remarkable private houses in the city of New York.” The paper named Ann Marshall one of the “belles of Old New-York”, originally from Aberdeen, Scotland. In New York, she lived with her father in an old Dutch mansion on Washington Street, marrying Robert Marshall in 1830. The Marshalls bought the Clendening mansion in 1845, along with six acres of land. They moved the house in compliance with the grid, locating it at Columbus and 104th. This article says that the name “Sharon Homestead” had been given by the Clendenings because the garden was filled with roses of Sharon. “The house was of the Colonial style, painted white and showing huge green blinds. It has a hall twenty feet wide and its furniture…would delight the soul of an antiquary.” In the 1880 Federal census, Margaret is still living in her parents’ home, still a single woman. There is a record of her death in 1928, at age 84, when she was living at “86th and Broadway.” Her brother James died much earlier in New York; both are buried in Greenwood Cemetery. The news article about Ann Marshall says she was buried at Greenwood, so we might assume that Robert Marshall is buried there also. In November 1897, the New York Tribune reported that the Marshall homestead “comprising the block front on the west side of Columbus Avenue between 103 and 104 Streets” was sold to Solomon Rothfeld for $230,000. It’s difficult to pinpoint when the Clendening/Marshall home disappeared. However, in a 1913 article in the Real Estate Record & Guide, there was an announcement that, at the SW corner of 104th Street, the Michael E. Paterno Realty Company was building a “house.” The Clendening name lives on In 1842 the Croton Aqueduct was completed, bringing fresh water to New York City. In the Bloomingdale neighborhood, a part of the system was above ground south of 110th Street. There, a thirty-foot wall was constructed between Ninth and Tenth Avenues – 100 feet west of Ninth (Columbus), according to Peter Salwen’s history. Because it was in the area of the former Clendening farm, it became known as the Clendening Bridge or the Clendening Wall. A final use of the Clendening name — for another structure no longer in existence — was for the Clendening Hotel, located at Amsterdam Avenue and 103rd Street, on the southwest corner. That corner had an earlier hotel named the Kenesaw; one reference called it “a family hotel,” and a two-story frame structure. I haven’t found a record of the tear-down of the Kenesaw and the building of the Clendening Hotel, which was an “apartment hotel” popular at the time. The Real Estate Record and Guide notes that Judson Lawson purchased the Kenesaw in 1900. In 1906 Lawson leased his property — described as a seven-story and basement apartment hotel — to Ewen Hathaway of the Clendening Company. The description of the leased structure appears to be the same building as pictured in these postcard images of the Clendening. In 1908, a parlor, bedroom, bathroom suite for two persons rented for $4 or $5 a day, according to a newspaper advertisement. Eventually, the Clendening became a not-so-nice accommodation, and it was taken down. Today, the site is occupied by a 1965 structure that is one of the collection of buildings comprising the NHCHA project, Frederick Douglass Houses. Sources

The New York Times archive Old newspapers on www.genealogybank.com Census information on www.ancestry.com Blog posts on www.daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com Museum of the City of New York: Randel Maps online Salwen, Peter Upper West Side Story: A History and Guide New York, Abbeville Press, 1989. On Google Books: “New York and Vicinity during the War of 1812-15 being a military, civic and financial local history of that period” Volume 1 On Google Books: “The New Yorker: A Weekly Journal of Literature, Politics, Statistics and General Intelligence” Volume 1 – 1836 On Google Books: Scoville, Joseph A., The Old Merchants of New York City published by Lovell in 1889, Volumes 3 and 4 On www.rootsweb.com: “Clendening” genealogy by Loraine Montferret Real Estate Record and Guide online at Columbia University Stokes, I.N. The Iconography of Manhattan Island 1498-1909 (v 6) New York: Robert H. Dodd 1915-1928. Online version.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |