|

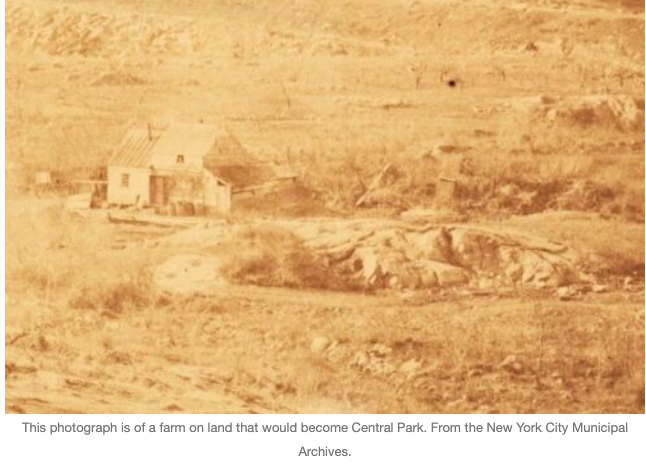

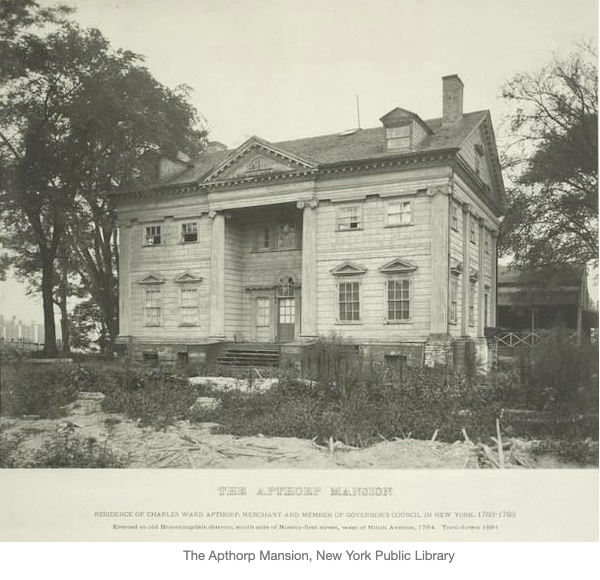

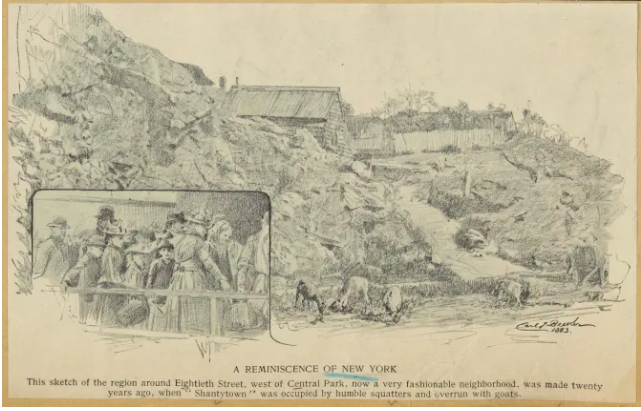

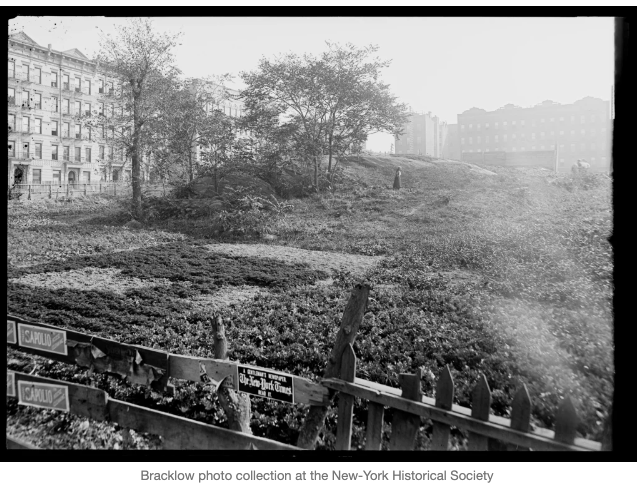

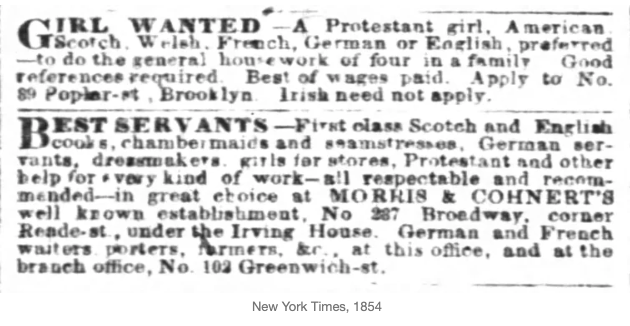

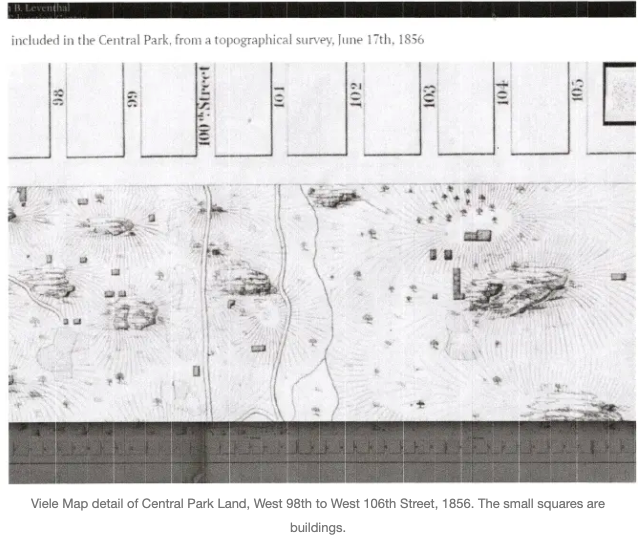

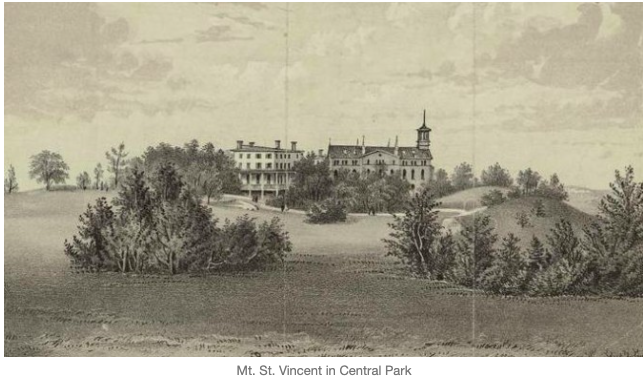

by Pam Tice, member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group Program Committee A recent question from a family researcher led me to the 1855 New York State census. As I located our Bloomingdale neighborhood in the city’s 12th Ward, I discovered how the pages of the census could become a lens into life in Bloomingdale in the mid-19th century. This was Bloomingdale before the Civil War, the Lion Brewery (1858), the 9th Avenue El (1879), and before most of the streets were laid out. New York City historians covering this period characterize the Bloomingdale neighborhood before the Civil War as a place of “country seats,” many developed in the late 18th and into the early 19th centuries by wealthy merchants. They built in the bucolic Bloomingdale to escape the crowded downtown, especially when a cholera or smallpox epidemic threatened. There’s scant attention paid to the working-class and poor residents of the neighborhood except to note that there was a “village” around 100th Street. Even as late as 1868, in an Atlantic Monthly article, Bloomingdale was described as a rural village near the city with family mansions and large asylums for “lunatics and orphans.” (The Bloomingdale Insane Asylum opened in 1821 and the Leake and Watts Orphan House opened in 1843.) The author describes the Bloomingdale Road as “Broadway run out into the country,” a road serving “fast-trotting horsemen.” The Hudson River Railroad runs beside the river with “much of the intervening ground occupied by market gardens.” In his book on the history of St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, located at today’s Amsterdam Avenue and 100th Street, John P. Peters describes two projects that changed the character of Bloomingdale. The first was the Croton Aqueduct, a “monumental structure” that emerged from underground at 113th Street and Tenth Avenue, turning eastward through Manhattan Valley, and running down the westside to West 84th Street. The other public project was the Harlem River Railroad, incorporated in 1846, and permitted to run locomotives along the Hudson from West 30th Street to Albany beginning in 1849. Peters describes this improvement as destroying the beauty of the country residences along the Hudson River, driving many owners to other regions. Bloomingdale went from being a country suburb to having a more numerous, poorer population. Another historian of the neighborhood in the mid-19th century, Hopper Striker Mott, describes Bloomingdale as a charming spot up to 1853, when too many shanties with poor inhabitants emerged, although he complains that this happened most often in the blocks south of West 68th Street. The 1855 New York State Census captures this change in Bloomingdale. There had been previous state censuses, starting in 1825. The 1855 census was the first to record the names of every individual in the household, and the relationship to the head of the family--the federal census did not do this until 1880. Citizens were urged to prepare for the visit from the Census Marshal in an article in the The New York Daily Herald in early June, 1855. Our local history group defines Bloomingdale today as the area between West 96th and West 110th Streets, Central Park West to the Hudson River. In 1855, this area was just a portion of the 12th Ward’s Election District 1 (ED1). The Ward also had four additional election districts, encompassing all the east and west sides of Manhattan, north of 86th Street. On the east side, Randall’s and Ward’s Islands in the East River were included in Election District 2 which covered the Yorkville neighborhood. District 3 covered Harlem, and District 4 was further north, covering Manhattanville. District 5 covered the topmost part of Manhattan. An 1857 article in The New York Daily Herald provided a description of all the 12th Ward Election Districts. Election District 1 containing Bloomingdale had a northern boundary of West 120th Street with an eastern edge at Fifth Avenue, the southern edge at the north side of West 86th Street, and the western boundary at the Hudson River. Locating a particular resident is a challenge as there are no street addresses in the 1855 census. We assume that the Census Marshals moved around in some orderly fashion; the only was to determine this is to look at the date of each recorded page, and assume that the dwellings listed are in some proximity. If there is a recognized mansion or institution it can help place the other dwellings geographically. Another method is to use the numerous city directories of the period to find a listing for a resident. However, many listings simply say “Bloomingdale.” My colleague in the history group, Rob Garber, did in fact check numerous names in the directories but relatively few of Bloomingdale’s residents were found. Another tool is the 1851 Dripps Map that places some of the mansion owners. The most surprising feature of the 1855 population census was the first two columns noting the value of each structure the family lived in, including the land, and the material used to build the dwelling. There were no instructions as to how the value was to be calculated. The information for each person included the usual census questions regarding name, age, gender, race, and birthplace, whether another country, another U.S. State, or another county in New York State. Additional columns captured the length of residence in the current place, occupation, citizenship (and therefore voting) status, ability to read and write, and if a landowner or leaseholder. The final column covered whether the person was blind, deaf and dumb, or insane or idiotic (19th century words). If the person was “colored,” whether he was taxed. At this time suffrage was granted to black males if they owned unencumbered property valued at $250 or more. If the person was of foreign birth, it is noted whether he or she is naturalized. An alien could become naturalized after five years residence in 1855; citizenship was automatically granted to wives of U.S. citizens. The Marshal was also to record on a separate schedule marriages and deaths in the past year, with questions about each. Other non-population schedules for each district sought information on farms and crops, shops and factories, details about animals, such as horses, mules, oxen, cows, swine, and sheep. The news article pointed out that this was especially important in the 12th Ward of the city where Bloomingdale was located, since the City Council had just passed a law that there should be no swine kept except in the northern districts of the city. There was also a separate schedule to report churches, schools, hotels, taverns, stores, and newspapers in the district. The Census Marshal who walked the 12th Ward’s Election District 1 was A. C. Judson. He lived in Election District 3, on the east side of Manhattan. His occupation was “civil engineer.” Reviewing the pages of the census, his mis-spellings become apparent, a common census defect. He also did not list many of the market gardens in the agricultural schedule although other marshals did so. Since he did not completely fill out the agricultural schedule, he also did not count animals. The pages of Ward 12, ED 1 show 1,635 people living there. There are 216 “families” and 188 dwellings. An estimate places about 130 dwellings between West 96th and West 110th Streets.In the case of the asylums and hotels, everyone was grouped as a “family,” whether a relative, a servant, an inmate, or a boarder. There were only 15 cases of multiple families housed in one dwelling. In only one dwelling there were four families housed. The Bloomingdale Insane Asylum housed 177 people, Leake and Watts Orphan House housed 136, and the House of Mercy, a home for “fallen women” was home to 12 people, making these three institutions responsible for housing nearly 20% of the ED1 population. Most of the hotels listed no boarders although the summer season was beginning Bloomingdale Dwellings The buildings of ED1 were categorized as stone, brick, frame, and “plank.” (Census Marshals in other districts referred to the un-framed homes as shanties.) For the most part, the stone and brick structures were valued above $20,000, although there was one stone building, perhaps an out-building on a former estate, valued at $240. Most of the buildings in the district were frame. The Elm Park Hotel at West 92nd Street (formerly the Apthorp/Jauncey/Thorpe residence) was valued at $600,000 perhaps because the real estate included some forty acres. The Bloomingdale Insane Asylum, the Furniss House at 100th Street, and the Paine house were all valued at over $150,000. Thirteen homes were valued at $20-$50,000. The greatest number of homes, seventy-four, were valued at $1,000-$8,000. Sixty-two homes were valued $300-$800. Twenty-one dwellings were listed as plank, seemingly constructed out of boards with no carpentry involved, and valued at less than $300. For the most part, these poorest dwellings housed laborers, but a few housed a mason or a gardener. ED1 did not have a “shanty-town” as other districts did, with many people living in plank structures, evidence of a shortage of what we call today “affordable housing.” As immigrants and working-class people flooded the city, landlords developed tenement housing, accommodating more people than was healthy into the older row-house structures of downtown Manhattan. It took until 1859 for an investigation of the city’s deplorable housing conditions. The people in plank houses uptown were perhaps more fortunate since they could live as a single family. The plank housing in Bloomingdale was often clustered together with very low-value frame dwellings, making small pockets of poor people. Nothing reached the numbers that made up the area called “Dutch Hill’ near 40th Street and First Avenue overlooking Turtle Bay, described in detail in a contemporary New York Times article published on March 21, 1855. New York City’s shantytowns were usually described with some measure of moralizing. Egbert Viele remarked long after Central Park was built that the residents of the area we now call Seneca Village was inhabited by the “foreign born in rude huts, living off the refuse of the city.” This observation of people living in the West Eighties would no doubt also apply to any of the other blocks of the upper westside Bloomingdale area. In an 1865 report, the Council on Hygiene described a squatter’s shack or shanty: “Rough boards form the floor, on the ground but a little raised above it; six to ten feet high with no fire place or chimney, just a stove pipe, which passes through a hole in the roof. The shanty was one room, maybe a second one as a bedroom. It has no sink. Drinking water comes in pails from Croton hydrants.” An 1859 article in the New York Sun asserted that most shanty owners ask permission of the landowner before they squat on the land, paying a small ground rent and raising vegetables on land otherwise unimproved. Contemporary articles about shanty-dwellers describe them as bone-boilers or making a living collecting cinders near the railroad tracks. But no one in ED1 gave bone-boiler as an occupation although there was German man in today’s Morningside Heights area who gave his occupation as soap-boiler. Immigrants Historians writing about New York City in this mid-century period cite population statistics that demonstrate the phenomenal growth of the city due to immigration. The city’s population more than doubled between 1845 and 1860, going from 371,223 to 813,660. German and Irish immigrants led in numbers. The German immigrants were driven by population growth which made land holdings smaller and smaller until families had to settle elsewhere in order to survive. Political revolution also drove immigration as young Germans chose to emigrate to avoid military service; others came for religious reasons. The Irish began arriving in increasing numbers as starvation caused by the potato blight created famine conditions. The 1855 State Census was the first in New York State to fully list nativity, showing the importance immigration held in the politics of the time. Immigration historian Robert Ernst charted the 1855 population by Ward, with the foreign-born making up 52.7% of the New York City population, the Irish at 33% and the Germans at 12.2%. In all of Ward 12, 5,831 people were Irish, and 2,130 were German; all other foreign-born numbered less than 200 individuals for each country, except the English who numbered 629. This pattern of nativity was reflected in ED1. Market Gardeners Of all the occupations the 1855 census reveals in ED1, gardeners stand out. In fact, growing vegetable gardens continued in our neighborhood until the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Photographers captured scenes like this: Historians who write about the city’s market gardens of the 19th century cite Louis P. Tremante’s thesis “Agriculture and Farm Life in the New York City Region, 1820-1870.” (The link to the thesis is cited below.) Tremante summed up his findings in a journal article listing the factors that made agricultural production on the city’s outskirts possible: a large and increasing population, high land values, a deep pool of immigrant labor, the availability of stable manure, and the presence of a large retail market. In our Bloomingdale neighborhood, the landowners holding onto their former estate land were able to lease it to the gardeners, creating short-term income from the land while they waited for the value to increase when housing was developed. Many German immigrants had been market gardeners in their home country. Manure to feed the soil was no problem. There was a huge population of horses in mid-19th century New York City and the collection and sale of manure to farmers in the region was an organized business. Finally, the city had a highly-structured food market system, although changes were underway at mid-century as food sales moved from the city markets to retail groceries and street vendors. The Bloomingdale gardeners most likely sold their products locally or moved it downtown to the Washington Market located in today’s Tribeca neighborhood. In Ward 12 ED1, most of the gardeners were German. This was typical of the time, as Germans often arrived with some resources which allowed them to lease land and grow market gardens. Irish workers listed as gardeners were usually part of a larger operation where they were servants in a mansion family or “employees” of a larger garden operation. In ED1, there were 40 gardeners as household heads; only eight were Irish, a few were English or French, but the group was predominantly German. There were an additional 28 gardeners who were “servants;” of these, 13 were Irish. Taking the Census, June 1855 Our Bloomingdale Census Marshal, Mr. Judd, performed his duty over eight days in June, 1855. He started on June 4, but well outside today’s Bloomingdale neighborhood. He went to the northeastern corner of ED1, at 120th Street. In Schedule 1, the population count of the census, Mr. Judd begins by listing nine German families with “gardener” as the head of family’s occupation. In his notes in the Agricultural section, he writes, “The Watts property is lying mostly to commons and is occupied by squatters to a great extent. Germans cultivate patches for gardens and make out to raise enough to live upon, in their way, but nothing more, with a large garden which is put into Schedule 1.” In another section of the agricultural schedule, he determined that the “Watts property” in this district was 42 acres. The property in this area was a part of the Archibald Watt estate. Mr. Watt and his family had a mansion estate further uptown in today’s Harlem, at about 139th Street near Seventh Avenue, part of the Twelfth Ward’s ED4. Mr. Watt and his step-daughter were fascinating 19th century New Yorkers who were real estate moguls. Sara Cedar Miller writes about the family in her new book Before Central Park. The Watt land that was in ED1 was mentioned in a family lawsuit of 1858 when 300 lots between West 118th and West 123rd Streets between 8th and 9th Avenues, were in dispute. While Mr. Judd has these German families “squatting” on the Watts land, the listing for the first family indicated they are “owner” which may have referred to a lease. Mr. Judd visited other families that day, reaching 25 dwellings in total. One was Thomas Dunlap, a florist at 8th Avenue and 116th Street, identified in a newspaper mention when his property was auctioned; he is also on the Dripps Map. Dwellings 13-17 are a collection of five plank houses. Mr. Judd’s fellow Census Marshal, Mr. Baldwin of ED4, commented in his notes that the market gardeners of the area had suffered from “drough” (sic) in 1854 but were hopeful early in the growing season of 1855 that their prospects were improved. Mr. Baldwin also commented in his notes that there had been a “prevailing epidemic” in the district which he called “diarrhoea” (sic) with the deaths of 28 males and 42 females, and 37 of them “foreigners” under the age of ten years. Mr. Baldwin counted market gardens in his agricultural schedule, listing thirteen such gardens. Despite the number of gardeners in ED1, Mr. Judd listed only five locations growing food in his Agricultural Schedule for the district. He ignored all the details of these operations, such as crops, their value, and animals kept. He noted that the Payne/Paine estate had seven acres and Weyman estate five acres under cultivation. Both of these were on the district’s western edge, below West 96th Street. He listed fifteen acres under cultivation by the Leake and Watts Orphan House, but nothing was listed for the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum even though there were six farmers on the staff there. He noted that the hotel at Elm Park near West 92nd Street had six acres under cultivation but the Striker’s Bay hotel at West 96th Street had no land being used for growing vegetables. Mr. Judd’s fellow marshal from ED4 listed the market garden crops of corn, potatoes, peas, beans, and turnips. From earlier estate sales ads in Bloomingdale, reference was often made to fruit trees, probably planted earlier in the century by the estate owners, and still producing. Mr. Baldwin also provided some detail on the crop value of the thirteen market gardens in his district: those with ten acres grew food valued $3500-$4500; those that were three or four acres grew food valued at $1000-$2000. The other 1855 non-population schedules Mr. Judd listed only two businesses in ED1 that qualified as “Industry.” Thomas Nafie, found in the population schedule for ED4, had a “chemical works” employing two men and a boy with a monthly wage of $35.00 for all. Mr. Nafie lived in a boardinghouse in ED 4 and his manufacturing may have been lampblack, according to the note on his occupation. It’s not clear where this business was located. Thomas Allen, also not found in the ED1 population schedule, is listed as the owner of a broom factory, employing seven men and two boys with average monthly wages paid at $30.00. The factory made 60,000 brooms annually with a value of $12,000. The work was all by hand. There were three homes in the population schedule where the family head was listed with the occupation of broom-maker. Dwelling #131, headed by Joseph Knapp, appears to be the broom factory. Mr. Knapp, from Connecticut, and his wife and three children live there with four “servants,” all listed as broom-makers. Mr. Judson also made the following note: “In this district here are many establishments for making Rope that are doing nothing and have done nothing for the past year. Also, an establishment for manufacturing glass. I have endeavored to get at the value of the property and put it on the Schedule.” Whether or not they were working, there were five homes in ED1 where the head of the family had an occupation involving rope. No one on the ED1 population schedule gave an occupation regarding glass. However, this glass factory, located at Broadway and West 104-105th Street, was advertised for sale in The New York Daily Herald in 1855 and again in 1863. On yet another schedule, the count of marriages and deaths in the district, Mr. Judd noted two marriages and forty-eight deaths. Twenty-seven of the deaths took place at the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum. Of the twenty-one other deaths, fifteen were children who died of diseases such as measles, whooping cough, scarlet fever, cholera, and consumption. The six adults who died had heart problems, consumption, typhus, or simply old age. More alarming are the deaths in ED2 covering Ward’s Island where over 2,300 deaths were listed, including hundreds of children. In these additional schedules, Mr. Judd noted that ED1 had five hotels, inns and taverns, and four grocery stores. There was no school in ED1 — the closest Ward School was in Ward 22, the District #9 School at 82nd Street and Eleventh Avenue, today’s West End Avenue. There was also a school in Manhattanville. There was only one church in ED1, St. Michael’s Episcopal at Tenth Avenue and 99th Street. There was a Catholic Church in Manhattanville, a Presbyterian Church around West 84th Street, and the Dutch Reformed Church at West 68th Street. Other Occupations in Bloomingdale Anyone working in a dwelling and not part of a family was labeled “servant” to show the relationship in the family. Additionally, their occupation was sometimes listed. The word “employee” was not used. There were about 194 servants in ED1, and their occupations ranged from gardener to ropemaker if they were working in the home of a business owner. This was a time when a home and a business tended to be in one place in the rural parts of the city. The servants in the mansion houses and hotels were listed as coachman, cook, waiter, governess, hostler, or chambermaid. In the census pages of ED1, those who were “laborers” tended to be Irish, reflecting a lack of skilled training. There were 43laborers as heads of families, and numerous others that were part of a family or mansion staff. Mr. Anbinder states in his book on immigration that only 12% of the “famine Irish” had a trade, so they had to take the low-paying, menial jobs. Also, many recent Irish immigrants did not speak English. Anbinder describes these workers as taking unskilled construction jobs, digging foundations, carrying heavy loads of bricks and mortar to masons, hoisting lumber to carpenters. They worked six days a week, ten hours a day, 7 am to 6 pm, with a dinner break at noon. Some eventually learned skills. This was the workforce that built Central Park, the city’s infrastructure, and its buildings. Other occupations in Bloomingdale tended to be held by those of a certain nativity. Three of the four blacksmiths were Irish, as were the two of the three policemen. The three builder/contractors were English. The tailors, and three of the four grocers were German. The mansion owners were labeled gentleman, or lawyer, or merchant. They tended to be born in the United States, with Mr. Carrigan from Ireland and Mr. Marshall from Scotland the exceptions. Mr. Carrigan was President of the Emigrant Industrial Savings Bank, and had five servants to help care for his wife and five children. (It was the Emigrant Savings Bank records that helped NYU researchers studying the Irish immigrants of Ward 12, sharing their research here. Women Residing in Bloomingdale There were fifteen dwellings with a family headed by a woman in ED1 of the census. Generally, women in this census were counted as the wife of a head of the family, or a servant living in another family’s home. Only one woman heading a family was given an occupation, that of seamstress. She had a young child and employed a 14-year-old girl as a servant. Three of the women were black, including a widow living alone, and a younger woman who housed a mulatto female boarder with a small child. Three of the women were widows with older children living with them. Two elderly women in Bloomingdale are noticeable: Mrs. Eliza Maier, age 78, is in her mansion “Willow Bank,” near West 118th Street, surrounded by family members and servants to care for her. Mrs. Isabella Weyman, age 80, in her mansion “Mount Aubrey,” between West 93rd and 94th Streets near the river, with her gardener and his family living in her home. Her daughter, Caroline, married H.W.T. Mali, the Belgian Consul, and was nearby in her home near West 113th Street and the Hudson River. Female domestic servants, most often Irish women, were given occupations, that of cook, seamstress, waiter, or laundress. Irish women were fortunate to find a job as a servant because it gave them shelter also. There is a well-documented history of such women being able to save some of their earnings to help other family members back home, and to help them emigrate in the chain-migration style of Irish families. However, as Irish prejudice grew in this decade, many families did not want young Irish women in their homes. Employment agencies advertising domestic jobs specifically stated “Protestant only” and “no Irish need apply.” Bloomingdale’s Black Families There were very few black citizens living in Bloomingdale at mid-century. The 1855 census lists the two black women heading families, mentioned above. There were two other families headed by men, one was a cook with a wife and children, and the other was a “jobber” with a wife and child. The cook lived in a modest two-family dwelling (valued at $300) with a young German family, an unusual arrangement in this time of strict racial segregation. The other black men living in Bloomingdale were a waiter at the Woodlawn Hotel, and two men who were hostlers at Stryker’s Bay Hotel, taking care of the horses. In the home of the broom-maker, Joseph Knapp, there is a 60-year-old black woman, a servant, but no was occupation was listed. Following the Census Marshal Mr. Judd performed his duty over eight days in June, 1855. We’ve already covered Mr. Judd’s first day, June 4, when he listed dwellings 1-25 in the upper section of ED1, at West 120th Street, an area well-outside Bloomingdale. On June 5 and 6, Mr. Judd worked his way south. On June 5 he appears to be working his way west, listing dwellings 26-47. One of them the Meier mansion at 118th Street near the Hudson. He also listed the Carrigan mansion at West 114th Street and the Bloomingdale Road, and the Whitlock mansion at West 109th Street. The recording of dwellings and people on June 6 provides an opportunity to demonstrate how one might make a guess where the Census Marshal traveled. That day lists dwellings 48-79, including many inexpensive frame and plank dwellings clustered in numbers 53-69. As population grew in New York City, the land that would become Central Park had seen “the proliferation of marginal subsistence farmsteads, small dwellings, and rented or illegally erected shanties” according to the first of the Hunter reports studying the northern quadrant of the Park in 1990. Could 1855 dwellings be the miscellaneous small buildings shown on Egbert Viele’s “Map of the lands Included in the Central Park from a topographical Survey, June 17, 1856”? Viele’s work in surveying the pre-Park lands can be viewed here. This map reflects the Park as originally planned, to 106th Street; the blocks up to 110th Street were added in 1859 On June 6, Mr. Judd listed first that day a plank dwelling valued at $200 where an Irish girl, Mary McLaughlin, 15 years old, was the head of the household for her seven brothers and sisters, age two to thirteen. The next dwelling housed Andrew Cullen “the keeper of the magazine.” On some early maps of this area, what we call the Blockhouse today, in the Park’s northwest corner, was labeled “the Magazine.” This is the structure that was built as part of fortifying the city during the War of 1812. Dwelling 51 on June 6 is a substantial frame house occupied by Benjamin Sutton. Could this be the Burrowes mansion that stood at the top of the Great Hill in today’s Central Park? Mr. Sutton owned the mansion starting in 1851, but real estate records show that he sold it to John Purple Howard in 1852. Could the Sutton family still be there? The placement of the dwelling near the house of the “magazine keeper.” suggests this might be possible. The Hunter report of 1990 reports that a network of lanes in this area gave access to the Great Hill and the Burrowes mansion. Of interest to today’s historian is the geo-mapping of all the structures of the Park’s northern quadrant by the Central Park Conservancy; some of these could be the ones Mr. Judd listed in 1855. Dwelling 55 was a plank home valued at $300 housing an older couple with no children living with them. The family head, James McLaughlin, gives his occupation of “lamplighter.” An 1852 news article reported a plan to “light 96th Street with oil from Fifth Avenue to the Bloomingdale Road.” It’s possible that Mr. McLaughlin was the man hired to keep those lamps lit. Regarding the Central Park buildings and population, of note is the counting of the Mount St. Vincent Academy at around West 104th Street, on the eastern side of the Park, west of Fifth Avenue. For some reason, this population was included in ED2, even though it is located in ED1. Mt. Saint Vincent, owned by the Sisters of Charity, was on the hill to the east of the Park’s East Drive which had been the Kingsbridge Road. By 1855, there was a main building, a chapel, a chaplain’s residence, a barn, poultry house, and school building. Several female students were housed there. Mr. Judd’s day on June 6 ended at Mr. Marshall’s home at Columbus Avenue and 104th Street, formerly the Clendening estate, a place covered in an earlier blog post. When Mr. Judd started his work again on June 9, covering dwellings 80 to 101, there was another cluster of nine homes of low value. In this day’s pages there was another grocer, a multi-family dwelling with four families, and two blacksmiths. He ended his day further south, on West 95th and West 96th Street where my colleague Rob Garner was able to identify two owners of large frame dwellings. Perhaps Mr. Judd worked his way down from West 104th Street that day, covering dwellings on both sides of the Croton Aqueduct structure. On June 11 Mr. Judd covered only a few houses but also visited the neighborhood institutions: the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum, the Leake and Watts Orphan House, and the House of Mercy which was a home for “fallen women” on the north side of West 86th Street near the river. On that day Mr. Judd listed all the workers and inmates, on his population schedule, covering several pages. He also listed the Elm Park Hotel at West 92 Street that day. On June 14, Mr. Judd listed dwellings 118 to 148. There is another possible anomaly here; dwelling !20 is a hotel operated by Edwin Luff. My colleague Rob Garner has identified him as a well-known hotel keeper with a hotel at Sixth Avenue and West 110th Street in 1863. If he’s operating the same business in 1855, then he fits into ED1 of the 1855 census. It may be possible that Mr. Judd included this hotel along with the Elm Park in his work on June 11 but had to put a few entries at the beginning of a page which was subsequently filled in on June 14. The remainder of his work on this day is in the westside Bloomingdale neighborhood. Several of the homes and businesses were clustered around West 100th Street, so this group is perhaps the “village” that historians have described. There was a flax man here, and a twine spinner, and others in the rope and broom business, including Mr. Knapp and Mr. Williams. There was a baker, a shoemaker, and a liquor store owned by Somerset Kinnaird who is also listed as a policeman. Mr. Kinnaird’s store is listed in a city directory on Broadway between West 98 and 99th Streets. The value of his dwelling is quite high, $30,000, which seems high for a store. Again, a guess: could this building be the old Abbey mansion which was formerly operated as a hotel? The structure was the old Humphrey Jones mansion that had been on 11th Avenue between West 102 and West 103 Streets since the 18th century. The Abbey property also included a seven-room cottage and garden; it’s possible that the former hotel was empty but the farmhouse occupied. The Abbey burned in either 1857 or 1859; in 1860, Mr. Kinnaird is living on “Dixon’s Row” on West 110th Street. The St. Michael’s Episcopal Church minister, William Richmond, is in this group. John and Bridget Cavanagh are also listed. John, age 52, is the only person in the district listed with a disability; his eyes were “burnt out” since he’d “been blasting rocks since he was 14.” When Bridget Cavanagh died the following year, a newspaper announcement on July 3, 1856, invited friends to attend her funeral “at her late residence, West 107th Street and Bloomingdale Road.”

Mr. Judd ended his day at the Woodlawn Hotel at West 107th Street and Eleventh Avenue. This was the second Jones mansion, built by Nicholas Jones, son of the previously mentioned Humphrey. On the seventh day, June 21, Mr. Judd continued working around West 100th Street where he listed the Furniss mansion located between streets that became West End Avenue and Riverside Drive. The Furniss Family (spelled “Furnace”) were not there but their servants were counted. The Stryker’s Bay Hotel at West 96th Street and the Hudson River was included. In an 1856 advertisement, an excursion to Stryker’s Bay and Woodlawn Hotels was offered with a steamboat bringing guests up the river for a Sunday afternoon’s enjoyment on the grounds of the two hotels. Stryker’s Bay was also a popular spot for New York City’s military companies who scheduled target practice excursions. There were more businesses counted on this day: a shoemaker, two grocers, a broom maker, and a blacksmith and the home of a policeman. Mr. Twine, a builder listed in a directory at West 100th Street and Broadway, is on the schedule that day. Mr. Twine had just finished building the second St. Michael’s Episcopal Church after the original building burned in 1853; he was also the Sexton for the church. David Jackson, Ward 12’s one-time Alderman, lived here. Further south, at West 92nd Street close to the river, was Dr. Valentine Williams, the local physician, written about with fond memory in Hopper Stryker Mott’s book. Mr. Schieffelin’s mansion was also in this area at West 92nd Street near the Hudson. One of the families listed in this section may have been renting it; Mr. Schieffelin ran newspaper advertisements offering the rental of his mansion which included five acres, a barn, and a “bathing house” on the river. The final day of spring the census was on June 23, listing dwellings 174-188. These included Mrs. Weyman, previously mentioned. Mr. Payne, which Judd should have spelled Paine, an attorney, was nearby in a grand house valued at $150,000 with 22 acres noted. In his book about the wealthy New York families, Moses Beach credits Mr. Paine as one of the principal movers behind building the city’s “new opera house” which may have been the 1854 Academy of Music built to replace the Astor House after its disastrous riot in 1849. This ends a description of Bloomingdale revealed by the 1855 census. Sources “Along The Hudson River At New York” The Atlantic Monthly. Vol XXII, No. CXXIX, July 1868, pp1-9 Anbinder, Tyler. City of Dreams. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Co., 2016 Ancestry.com. “New York, U.S., State Census, 1855” (database on line) Provo UT, 2013 Beach, Moses S. Wealth & Biography of the Wealthy Citizens of New York City. New York: New York Sun Office, 1855 accessed: http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/digital/collections/cul/texts/ldpd_6316657_000/ldpd_6316657_000.pdf Bolger, Eilleen “Background History of the United States Naturalization Process” (Social Welfare. Library.vcu.edu (accessed May 2023) Ernst, Robert. Immigrant Life in New York City 1825-1863. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1949 Family histories at www.familysearch.org Hunter Research Inc. A Preliminary Historical and Archaeological Assessment of Central Park to the North of the 97th Street Transverse Volume 1 and 2. Central Park Conservancy and The City of New York 1990 (Accessed at http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/arch_reports/444_A.pdf) Hunter Research Inc. Archival Research and Historic Resource Mapping North End of Central Park Above 103rd Street, Borough of Manhattan, New York City, Summary Narrative. Central Park Conservancy, 2014 (Accessed at http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/arch_reports/1617.pdf) Miller, Sara Cedar. Before Central Park. New York: Columbia University Press, 2022 Mott, Hopper Striker. The New York of Yesterday: Bloomingdale. New York, The Knickerbocker Press 1908 Newspaper articles www.newspapers.com Peters, John P. Annals of St. Michael’s. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1907 Rode, Charles R. The New York City Directory. 1st-13th publications, 1842-1855 Rosenzweig, Ray and Elizabeth Blackmar. The Park and The People, A History of Central Park. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1992 Spann, Edward K. The New Metropolis, New York City 1840-1857. New York: Columbia University Press, 1981 Still, Bayrd. Mirror for Gotham: New York as Seen by Contemporaries from Dutch Days to the Present. New York: Fordham University Press, 1994 Tremante, Louis P. “Agriculture and Farm Life in the New York City Region, 1820-1870” (Ph.D. dissertation, Iowa State University, 2000) Access here: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/38904832.pdf Tremante, Louis P. “Agriculture in the Vicinity of Mid-Nineteenth Century New York City” New York History, Vol. 97, No. 3-4, Summer/Fall 2016. Pp 265-292 Trow’s New York City Directory for 1853 and 1854 Valentine, D. T. Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York for 1855 Viele, Egbert. Map of the lands included in the Central Park, from a topographical survey, June 17th, 1856. (accessed: https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:3f463277s).

1 Comment

|