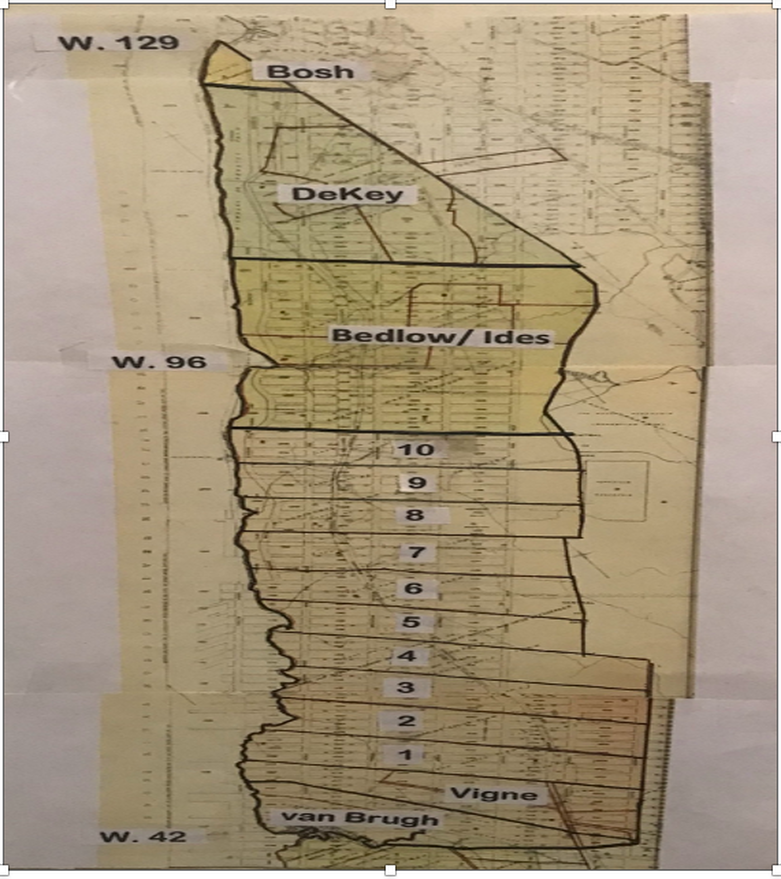

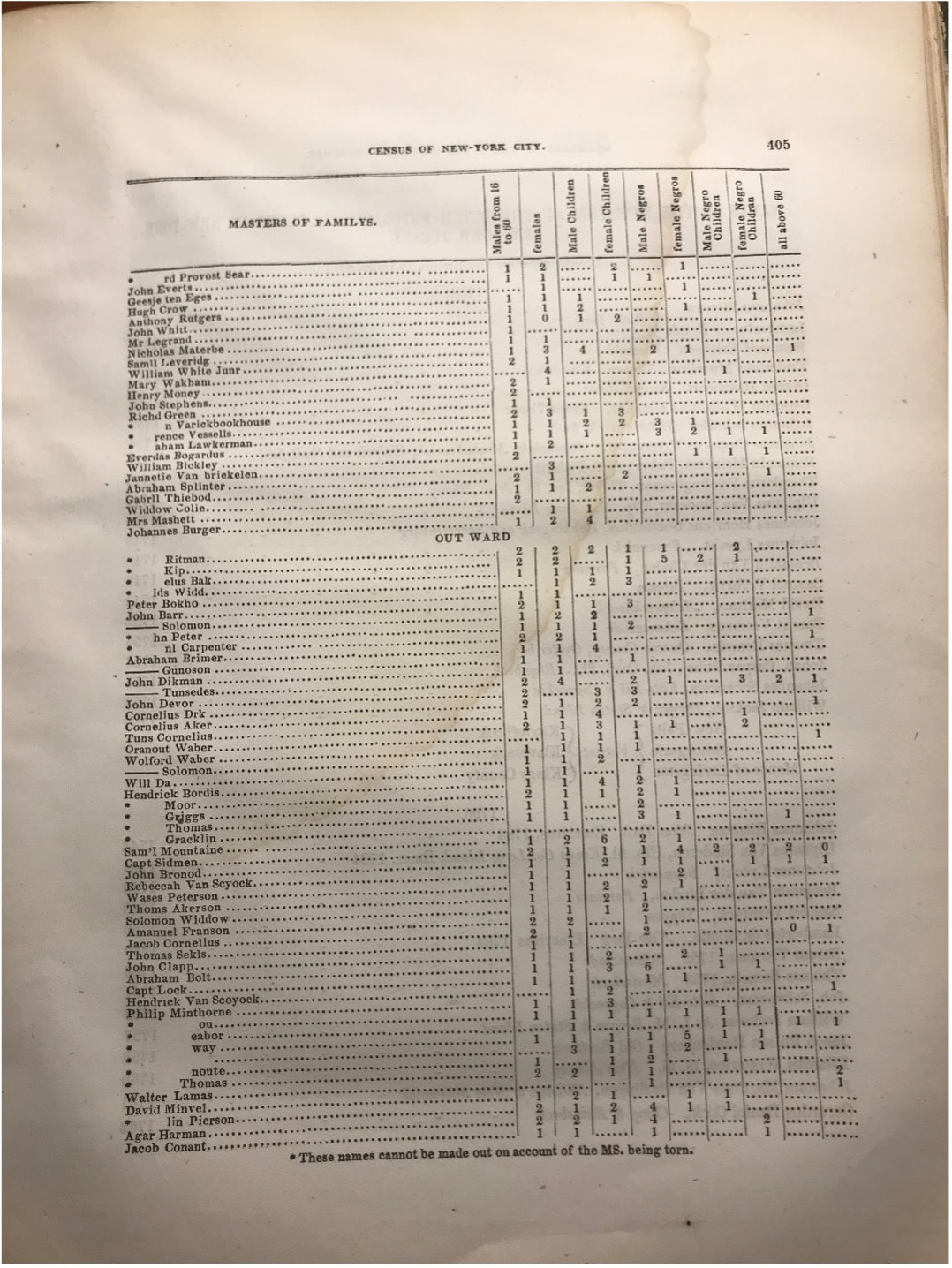

written by Gil Tauber, member of the BNHG Planning Committee The Bloomingdale district of colonial New York was a rough triangle of land, about 3.5 square miles in area, stretching along the Hudson River from about 42nd Street to 129th Street. Its southern boundary was a broad creek, bordered by marshes, known as the Great Kill. It was bounded on the east by the Town of Harlem, a peculiar municipal entity that had been established by Peter Stuyvesant and continued by his English successors despite being entirely within the City of New York. Accounts of the history of Bloomingdale rightly note the importance of the Bloomingdale Road. First laid out about 1708 as part of the provincial highway system in the Province of New York, the road is credited with changing Bloomingdale from a rural backwater to a district of fashionable country estates. In the 19th Century, its prestige was such that property near the road, even far to the south, was described as being in Bloomingdale.[1] However, there was a Bloomingdale well before the road, and the creation of the road was itself a step in a more gradual process. This paper examines the history of Bloomingdale up to the period when the road was laid out. THE CREATION OF NEW HARLEM The early history of Bloomingdale is closely tied to that of Harlem. Soon after the establishment of the Dutch colony, its leaders recognized the agricultural potential of the flat, fertile lands that later became Harlem. In the 1630s the Dutch West India Company offered generous terms to people willing to farm there.[1] Several large tracts were taken up. However, in the course of bloody conflicts with the Indians in the 1640s, initially provoked by the incompetent Director of the colony, Willem Kieft, many settlers were killed and the outlying farms had to be abandoned.[2] By 1656, conflict with the Indians had subsided to the point where Kieft’s successor, Peter Stuyvesant, could plan to reestablish a settlement on the abandoned lands in upper Manhattan and elsewhere. Stuyvesant recognized that large individual farms would not be defensible. He therefore required, in an ordinance dated January 18, 1656, that settlers live in a compact villages.[3] This policy was reflected in the grant or ordinance of March 4, 1658, establishing a new settlement “at the end of Manhattan Island.[4] It refers to the settlement only as a “New Village,” but by the fall of that year it was referred to in official documents as the new Village of Harlem or New Harlem.[5] As built, the village of New Harlem was located around the present 125th Street and First Avenue.[6] The Stuyvesant grant gave New Harlem certain characteristics of a municipality, notably the right to have its own local court and magistrates, and control over the unallotted land within its boundaries. However, it did not clearly define those boundaries. It also promised to protect New Harlem from the establishment of any new village that would compete with it, and further promised that a “wagon road” would be built between the new village and New Amsterdam. The First Nicolls Charter for New Harlem Eight years later, in May 1666, New Harlem’s municipal rights were confirmed and expanded in a grant by the English governor Richard Nicolls. This document gave New Harlem[7] the peculiar status of having “the privileges of a Towne, but immediately depending on this City [New York] as being within the Libertyes thereof.”[8] The Nicolls charter also defined the western boundary of the town as a line extending due south from the Hudson River, at what is now the foot of West 129thth St., to the East River at what is now East 74th St. The Town of New Harlem was given jurisdiction over everything east of that line to the end of the island at Spuyten Duyvil.[9] In addition to its municipal rights within its boundaries. New Harlem was given some very important additional rights over the adjoining land. Nicolls wrote: “the Inhabitants of the said Towne, shall have Liberty for the conveniency of more Range for their Horses & Cattle, to go farther west into the woods beyond the aforesaid Bounds, as they shall have occasion. And no Person shall bee permitted to Build in any manner of House or Houses within two Miles of the aforesaid Limitts or Bounds of the said Towne without the Consent of the Inhabitants thereof.” This provision was intended to make explicit Stuyvesant’s promise of protection from competing settlements. Thus, the freeholders of Harlem were, at least on paper, given veto power over the future development of a large swath of Manhattan Island outside their boundaries. This amounted to about four square miles, including most of what later became Bloomingdale. The Revised Nicolls Charter for New Harlem Seventeen months later, on October 11, 1667[10] Nicolls issued a revised charter that must have involved some horse-trading. First, it enlarged the town’s jurisdiction by adding the islands in the vicinity of Hell Gate, i.e., Randalls, Wards, and another nearby island that is now part of the Bronx mainland. Second, Nicolls agreed that the town “shall continue & retain the name of New Harlem.” The provision about grazing animals beyond the Town limit was changed to refer to “freedom of commonage for range & feed of Cattle & Horses,” which would appear to limit this right to the Common Lands, i.e. lands not yet in private ownership. The new charter retained the right to block new construction within two miles of the town line, but now specified that permission for such construction required consent of a majority of the inhabitants.[11] We do not know whether the inhabitants of New Harlem ever tried to exercise their right to block construction west of the Harlem line. Nevertheless, the provisions of their successive patents from Gov. Nicolls suggest that they had a keen interest in the land west of the Harlem Line beyond being a place to graze their livestock. Settlement west of the line could give rise to a competing community. On the other hand, additional population would benefit New Harlem’s economy and institutions. THE PEOPLING OF BLOOMINGDALE The Syndicate’s Grant At the time of the English conquest of the New Netherlands in 1664, there was no European settlement in the area that is now the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The Dutch West India Company had made no permanent grants of land along the East River north of Turtle Bay (about the present 47th St.) and no grants along the Hudson River north of the Great Kill, the broad creek that flowed into the Hudson near the foot of the present 42nd St.[12], [13] On October 3, 1667, eight days before his revised grant to the freeholders of New Harlem, Governor Richard Nicolls conveyed a large tract north of the Great Kill to a syndicate of five men: Johannes van Brugh, Thomas Hall, John Vigne, Egbert Wouters, and Jacob Leenderts van der Grift. The tract stretched along the Hudson from the Great Kill northward 13,200 feet and back into the woods for a distance of 4,125 feet, containing in all 1,300 acres or a little more than two square miles.[14] This was the first and largest of several grants that conveyed Bloomingdale into private ownership. (See map below) None of the syndicate’s five members planned to spend much time behind a plow. All were wealthy or at least well off. Most had held public offices under the Dutch or English or both. Most had ties of business, blood, or marriage to some of the most powerful people in the colony. Van Brugh was a wealthy brewer. [Jean Vigne, also a brewer, was the stepson of Stuyvesant’s agent Jan Jansen Damen and the brother-in-law of Cornelis van Tienhoven, once the powerful secretary of the Dutch West India Company.[2] Thomas Hall and his fellow Englishman George Holmes were brought to New Amsterdam as prisoners in 1635 after a failed attempt by Virginia to seize a Dutch outpost on the Delaware. They were the first Englishmen in the colony. The two eventually became trusted agents of van Twiller; managed his plantations, and later became wealthy landowners in their own right. Wouters, also a planter, was a curator (trustee) of the Damen estate[3] and, after Van Twiller’s death, leased the former Director’s plantation from his Van Rensselaer cousins. Van der Grift was the brother of Paulus Leendertsen van der Grift, a skipper whom Stuyvesant, in 1647, had appointed to the lucrative post of Equipage Master of the West India Company’s ships. A later complaint to the authorities in Amsterdam noted that though Paulus “has small wages, he has built a better dwelling-house here than anybody else.”[4] If any of these men did more than just hold their new properties for resale, the labor of clearing, tilling, and tending would be done almost entirely by tenant farmers, hired hands, indentured servants, and slaves. The five partners divided up the land among themselves. Van Brugh, whom Stokes notes was by far the richest of the partners, received the most desirable parcel, 150 acres directly along the north side of the Great Kill. Jan Vigne received another 150 acres immediately north of the van Brugh tract. The remaining 1,000 acres was divided into ten lots, which were then distributed equally among the five men. Each lot bordered the Hudson for about 1,000 feet and extended inland for about eight tenths of a mile. If numbered from south to north, the ten lots were assigned as follows: Lots 1 and 2 went to Jacob Leendertsen van der Grift, who almost immediately sold them to Isaac Bedlow.[5] Lots 3 and 4 went to Thomas Hall and Lots 5 and 6 to Johannes van Brugh. The last four were divided between Egbert Wouters and Jan Vigne. It is not certain whether 7 and 8 went to Wouters and 9 and 10 went to Vigne or vice versa. Either way, Lots 7 and 8 were also soon sold either to Thomas Hall, who died in 1669, or possibly to his widow Anne Medford Hall The grant to the five partners in the syndicate comprised all of Manhattan’s West Side from about 42nd Street to 89th Street and extended inland to an irregular boundary between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. [6] The Bedlow Grant On February 13, 1668, Nicolls made a second grant, immediately north of the syndicate’s 1,300-acres, to Isaac Bedlow. [7] Bedlow’s grant of about 400 acres ran from 89th to 107th Streets. It was centered on a sheltered cove that, a century later, would be known as Stryker’s Bay[8] Isaac Bedlow was a merchant and a very successful speculator in land, as well as a city alderman. His numerous holdings, at one time or another, included Bedloe’s Island (now Liberty Island) and a large chunk of the Bronx. Says Stokes, “For more than 20 years after 1668 the records are silent about the Bedlow patent.” Bedlow died in February 1673. Shrewd as he was in his business dealings, he neglected to make a will, thus burdening his widow and children with years of litigation. A commission was appointed to audit and supervise his accounts. His widow Elizabeth was appointed administratrix on August 9, 1675. It took 13 more years until she was able to sell the Bloomingdale tract.[9] The eventual buyer was Theunis Ides (or Idens) van Huyse, of whom I will write more below. Further History of the Syndicate Lots As noted above by Stokes, little is known of the history of the syndicate’s lots during Bloomingdale’s first two decades.[10] Nevertheless, Stokes and his team of researchers were able to glean the following from available wills, deeds, and other records: Van Brugh held on to his 150-acre tract on the north side of the Great Kill. His heirs appear to have owned it until around 1700. Jan Vigne at some point sold his 150 acres to Jacob Cornellisen Stille. Stille in turn sold it to Wolfert Webbers, who had married Stille’s daughter Grietje in 1697. It remained in the Webbers family until the mid-18th Century.[11] Of the ten lots that the five partners divided equally: Lots 1 and 2, originally allotted to to Jacob Leendertse van de Grift, were sold within the year to Isaac Bedlow. [12] After Bedlow’s death in 1673, the farm passed to his daughters and their spouses. In 1698 there is a conveyance by the Bedlow heirs to Jacobus van Cortlandt (1658-1739), a future Mayor of New York.[13] By 1714, Lot 1 had become the property of Matthias Hopper.[14] Although no deeds have been found for the next transfer of Lot 2, it directly or indirectly passed from Jacobus Van Cortlandt, (d. 1739) to Cornelis Cosine. Cosine moved to Bloomingdale in 1741 when he was elected Collector of the Bowery Division of the Out Ward.[15] Lots 3 and 4 were initially allotted to Thomas Hall, who had died by November 1669. It is recited in a later deed that either Hall or his heirs sold these two lots to Theunis Cornellisen Stille, the younger brother of Jacob Cornellisen Stille. The date of this transaction is not known.[16] Lots 5 and 6 were Johannes van Brugh’s share of the Ten Lots. In 1696, van Brugh sold Lot 5 to the aforementioned Theunis Cornellisen Stille. Twenty-four years later, in 1720, the Stilles mortgaged their three lots (3, 4 and 5) to secure a loan of 300 pounds. By 1729, the property was owned by Stephen Delancey (1663-1741). This was Delancey’s Lower Farm, which he called Little Bloomingdale. A half century later it was owned by Stephen’s grandson James. James was an active Loyalist in the American Revolution and his estates were later confiscated by the new State of New York. In 1780, Little Bloomingdale was sold by the Commissioners of Forfeiture to John Somerindike for 2,500 pounds.[17] Lot 6 was retained by van Brugh until his death, which must have been prior to 1701, his heirs sold Lot 6 to Rebecca van Schaick, the widow of Adrian van Schaick for 75 pounds. Rebecca was already the owner of Lot 7, which her late husband had bought in 1697 from Anthony John Evertse, a free Negro. A few weeks after acquiring Lot 6 from the van Brugh heirs, Rebecca van Schaick sold both Lots 6 and 7 to Cornelius Dykeman. Cornelius Dykeman died prior to 1722, and the property was divided between his sons George and Cornelius. Lot 6 remained in the Dykeman family until 1763, when it was conveyed to Jacob Harsen.[18] It is not certain whether Lots 7 and 8 were originally allotted to Wouters or Vigne, either way they were soon acquired by Thomas Hall, who died in 1669, or possibly to his widow Anne Medford Hall, who lists them in a will made soon after her husband’s death.[19] But Anne Hall lived many more years. In 1686, she sold Lot 7 to John Evertse, a free Negro who, as mentioned above, sold it in 1697 to Adrian van Schaick, whose widow later sold both Lots 6 and 7 to Cornelius Dyckman. By Dyckman’s will, Lot 6 went to his son George and Lot 7 to his son Cornelius Jr. In 1745, the latter’s granddaughter Cornelia married Teunis Somarindyck, and the property was thereafter known as the Teunis Somarindyck Farm. In the deed that conveyed Lot 7 from Evertse to van Schaick, it is described as bounded on the north by land of Brant Skeyler (i.e., Brandt Schuyler). This Schuyler was a prominent citizen and the husband of Cornelia van Cortlandt.[20] Stokes states that “no other evidence of Schuyler’s ownership [of Lot 8] has been found.[21] However, see below regarding Lots 9 and 10. At some point prior to 1720, Theunis Ides expanded his farm, the former Bedlow grant, by acquiring Lot 10. In June of 1720, when he divided his land among his children and their spouses, the former Lot 10 went to his son-in-law Marinus Roelefse van Vleckeren, the husband of his daughter Dinah.[22] Several years earlier, in 1711, Marinus Roelefse had petitioned the Common Council for a “grant or lease of a tract of land belonging to the Corporation [i.e., the City] lying near the land of Theunis Ides …containing 150 acres or thereabouts.” There is no record of any action on this petition, but the acreage mentioned suggests that Lots 8 and 9 had reverted to the City. “The records reveal nothing further,” according to Stokes. Sometime between 1720 and 1729 Stephen Delancey purchased Lot 10 from Roelefse. He may have also purchased Lots 8 and 9 from Roelefse, assuming the petition of 1711 was eventually granted. More likely he purchased them directly from the City. Either way, as of 1729, Lots 8, 9 and 10 had become the country seat of Stephen Delancey (1663-1741), which he called Bloomingdale. Delancey, a descendant of minor French nobility, had come to New York in 1686 as a refugee from French persecution following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. In New York he became a merchant and amassed great wealth. Through his marriage and those of his children, he was allied with some of the most powerful families in the colony and became patriarch of a dynasty that wielded great influence in New York affairs until the American Revolution.[23] As noted above, in mid-1729 or shortly thereafter, Stephen Delancey also purchased Lots 3, 4 and 5. That estate he called Little Bloomingdale. Further History of the Bedlow Patent As noted above, the 1668 Bedlow grant was eventually purchased by Theunis Ides (or Idens) van Huyse. We know quite a bit about Theunis, mainly thanks to the journal of Jasper Danckaerts, one of two Labadist preachers who visited New York and neighboring colonies in 1679-80 to scout possible locations for a Labadist community in the New World.[24] While in Manhattan, they lodged with an elderly couple, Jacob Hellikers, a carpenter, and his wife Theuntje Theunis.[25]. The couple each had three children by earlier marriages and one child together. Theunis Idens was Theuntje’s son by her deceased first husband, whom we may call Iden van Huyse.[26] Born in the Netherlands, Theunis was an adolescent when his father died and his mother remarried the widowed Jacob Helliker. Moving to the New Netherlands, they lived first in Brooklyn, where the young Theunis fell into a life of dissolution and petty crime. It did not help matters that one of his brothers-in-law was a tavern keeper. When the Labadists met him Theunis was 41 years old, married with six children, and working a farm in Sapokannikan that he owned in partnership with his brother- in- law. But things were going very badly. “The devil had been assailing him for six years past,” Danckaerts wrote. “His wife was a very ill-natured woman, cursing at him and finding fault,’ and his children were saucy except for the eldest daughter. A slave he had long possessed was thrown by a horse and later died. A valuable canoe was dashed to pieces by a storm as his neighbors stood by and did nothing. His cows sickened. A daughter was injured in a fall. His hand was crushed felling trees. And he had a bitter falling out with his partner brother-in-law. He was remorseful about his former “Godless life,” but his troubles mounted. One day in April 1680, it became too much. He ran amok, demanding a rope to hang himself. His terrified wife and children sent word to the Helliker’s house. The Labadist preachers hurried to Theunis’ farm, where they calmed him, read him passages from the scripture, and convinced him that God had not forsaken him. Theunis confided that “he wished he could go and live alone in the woods, away from wicked men, for it was impossible to live near them and not sin as they do.” Afterward, Danckaerts and Sluyter spoke to Theunis’s wife and children about how they must behave toward the troubled man.[27] The following month, after a trip to the Albany area, the Labadists visited Theunis again. They found him much calmer and feeling a lot better. He said his wife had changed “as day from night.”[28] In June, as the preachers were preparing to sail back to Europe, Theunis came to bid them farewell. A week later, he joined the Dutch Reformed Church.[29] Following his recovery from what Peter Salwen has called “the earliest recorded nervous breakdown in New York City History,”[30] Theunis’s fortunes improved. He apparently became a respected member of the community since in 1687 he was elected assessor of the Out Ward.[31] In 1688, or perhaps early 1689, he sold his farm in what is now Greenwich Village and purchased the former Bedlow Tract. According to Stokes, he must have moved to his new farm before March 1689, when his eldest daughter Rebecca married Abraham de la Montagnie, grandson of one of the of the founding families of New Harlem[32] Over the next three decades that Theunis held his land, he probably worked it with the help of his son Eide van Huyse and his five sons-in -law. It is also likely that he had a number of indentured workers, if not slaves. On the 1703 Census his household includes one adult male Negro and five Negro children.[33] In 1720, by which time Theunis was over 80 and the Bloomingdale Road had greatly increased the value of his holdings, Theunis and his wife Janettje had their land surveyed into eight lots, which were numbered from south to north. These they conveyed to their children and sons-in-law as follows, starting from the northernmost:[34] No. 8 to Abraham De Le Montagnie, husband of their daughter Rebecca. Nos. 6 and 7 to their son-in law George Dyckman, who was married to their youngest daughter Catalina. His family owned what had been Lot 6 of the syndicate’s Ten Lots. Nos. 4 and 5 to their son Eide Van Huyse. Nos. 3 and 2/3 of No 2 to Mindert Burger van Evera, married to their daughter Sarah. No. I and 1/3 of No. 2 to Marinus Roelefse van Vleck, married to their daughter Dinah. This parcel corresponds to Lot 10 of the syndicate’s Ten Lots. Theunis owned an additional farm in Bloomingdale, which he gave to his daughter Maria, who was married to Jurien Rynchout. THE NAMING OF BLOOMINGDALE It is likely that, by the time Theunis Idens moved there about 1688, the name Bloomingdale was already being used for the area north of the Great Kill and west of the Harlem Line. It is also likely that the inhabitants of New Harlem were the first to use the name, at least in its Dutch form. The village of New Harlem, at about today’s 125th St. and First Avenue, was first so called in 1658[35]. The village of Bloemendael in the Netherlands is about two miles west of the original Harlem. Manhattan’s Bloomingdale was a similar distance west of New Harlem. It would have been logical for residents of New Harlem, who used the area to their west for grazing and other purposes, to refer to it jocularly as Bloemendael[36]. On March 10, 1688, the marriage register of the Reformed Dutch Church in New York records the marriage of Francisco Van Angola, young man (i.e., a bachelor), “Van Bloemendal” to Dorothee Bresiel, young lady, (i.e., maiden), “Van de Barbadoes,” the first living “op Bloemendal” and the second “op Frederick Philpszens land.” This is the first known use of the name Bloemendal in a written record.[37] The Dutch preposition “op” usually means “on” (in the physical sense), which suggests that “Bloemendal” might denote a specific farm or estate. On the other hand, in this context, it might also have the meaning of “at.” The entry in the marriage register indicates that the wedding took place at New Harlem. It also specifies, by the terms young man and young lady, that neither partner had been previously married. In an age of frequent early mortality, marriages involving widows and widowers were common.[38] It is almost certain that both bride and groom were Black. Most of the early slaves in the New Netherlands were brought from Portuguese territories in Africa or from Brazil. Angola or Van Angola was a common name among former slaves of the Dutch West India Company. Starting in the late 1630s, a number of the Company’s long-serving slaves were manumitted and settled on small grants of land along the West Side of the Bowery between today’s Houston and 14th Sts. [39] Dorothee was from Barbados, but the name Bresiel may indicate a connection with the Portuguese colony of Brazil. At the time, Barbadoes was a center of the transatlantic slave trade, in which Frederick Philipse was a major player. THE NORTHERN TRIANGLE Following Nicoll’s 1668 grant to Isaac Bedlow, there remained a large triangle of ungranted land to the north of the Bedlow grant. It ran from 107th to an acute angle between the Harlem Line and the Hudson River at what is now the foot of St. Clair Place, formerly West 129th St.[40] The end of the Harlem Line was described by the surveyor Casimir Goerck in 1785 as being the site of a certain sycamore tree. It was, according to Stokes, just west of 12th Avenue, very near the foot of the steps now leading down from Riverside Park.[41] In 1677 the northern tip of the triangle, amounting to about 30 acres, was granted by Governor Andros to Hendrick Hendricksen Bosh, a sword cutler.[42] Under the Dongan Charter of 1686, the now-truncated triangle became the property of the City of New York. In 1700, to help finance the construction of the new City Hall on Wall Street, this parcel was ordered surveyed and sold at auction. The winning bid was from John Miseroll Jr., yeoman, of Bushwick., who afterward assigned his bid to Captain Jacob DeKey. The final deed to DeKey gave the acreage as 235 acres, 3 rods and 18 perches and the price as 237 pounds.[43] Bosh’s 30-acre farm was sold before his death to Thomas Tourneur, a member of one of New Harlem’s leading families.[44] Tourneur already owned the farm when DeKey got the larger parcel to the south.. After Tourneur died in 1710, DeKey purchased the 30 acres from Tourneur’s heirs. No record of Jacobus DeKey’s death has been found, but his son Thomas advertised the farm for sale in 1732. In a deed dated before May 1, 1735, Thomas DeKey sold the property to Adriaen Hoogland and Harman Vandewater, who divided it between them. [45] Hoogland’s share was the farm conveyed by his executors to Nicholas DePeyster in 1785. In 1795, Nicholas DePeyster’s barn was on or near the site of Adriaen Hoogland’s house.[46] BLOOMINGDALE IN THE CENSUS OF 1703 There was very little systematic recording of land conveyances in late-17th Century New York. Nevertheless, in the colonial deeds, wills and other records found by Stokes, there are numerous mentions of land in Bloomingdale being bought, sold, bequeathed, leased, mortgaged, and foreclosed.[47] From this, one might imagine that Bloomingdale was a thriving agricultural community by the beginning of the 18th Century. However, the available evidence indicates that, prior to the construction of the Bloomingdale Road, which was in or about 1708, Bloomingdale was still populated by fewer than a dozen families. Prior to 1708, there were only two censuses of the Province of New York, those of in 1698 and 1703. Records of the 1698 census have survived for some counties, including lists of the names of the heads of households in each town. Unfortunately, detailed data for New York County (Manhattan) has not survived[48]. Even the subtotals for the individual wards of New York City in 1698 are no longer to be found. Much more information survived from the 1703 census, including lists of the heads of households in each of the city’s wards. At that time, the city was divided into six wards. Five of the wards covered the city’s built-up area, which was roughly south of Chambers Street. The entire remainder of the Island was included in the “Out Ward.” The Out Ward was itself divided into two parts. One part was the quasi-autonomous Town of Harlem, which was also the Harlem Division of the Out Ward. Everything west and south of the Harlem Line, including Bloomingdale, was the Bowery Division of the Out Ward. In addition to Bloomingdale, the Bowery Division included such areas as today’s Lower East Side, Greenwich Village, Chelsea and Kips Bay.[49] The results of the 1703 census of New York City were published in 1849 under the auspices of the New York State Senate.[50] On the following page is the table showing the households in the Out Ward, listed by “Masters of Familys.”[51] Unfortunately, the available data from the 1703 census must be taken with more than a grain of salt. It suffered from language barriers, physical damage to the records, and the probable reluctance of a wartime population to cooperate with census takers whose main job was to identify males, including boys as young as 16, eligible for conscription. The table breaks out data for Negroes but does not distinguish between slaves and free Blacks. This would have been an additional complication for the census takers, especially since there was an intermediate category of “half-slave,” in which the child of a manumitted person remained a slave for a set period. Note that Bloomingdale had had at least one Black landowner, John Evertse, mentioned earlier in connection with Lot 7 of the Syndicate’s lots. The transcribed list includes 51 households with a total of 342 people—men, women and children, white and Black—for the entire Out Ward.

The 1849 transcription has numerous gaps. After nearly 150 years, the original documents were already in poor condition. Notice the asterisked names and the footnote explaining: “These names cannot be made out on account of the MS. being torn.” Of the 51 households listed, 12 cannot be identified because either surnames or given names, or both, are incomplete or are entirely missing. Many of the names have idiosyncratic spellings that are difficult to match with individuals recorded in contemporary documents such as the Minutes of the Common Council. There is also the fact that, at this period, New York’s Dutch still commonly used patronymics rather than surnames. Out of the 51 household heads listed in the 1703 census, only seven can be identified with reasonable certainty as living in Bloomingdale. These are: John Dikman = Johannes Dyckman who on December 29, 1701, leased a farm in Bloomingdale from Jurien Rynchout, a son in law of Teunis Ides, for a term of six years. According to Riker, this Dyckman was not related to the Dyckman’s of Kingsbridge, an area included in the Town of Harlem. Persons in household: 2. Jacob Cornelius = Jacob Cornellisen Stille. (1643-1711) Jacob was overseer of highways for the Bowery Division in 1703. He was the father-in-law of Wolfert Webbers. Persons in household: 6 Tuns Cornelius = Teunis Cornellisen Stille (1656-1724), the brother of Jacob. Teunis bought Lots 3 and 4, formerly owned by Thomas Hall, and purchased lot 5 from van Brugh in 1696. Teunis Cornelisen Stille was Constable of the Bowery Division in 1708. Persons in household: 10 _____ Tunsedes = Teunis Ides van Huyse (1640-c. 1723). This is the Teunis Ides who in 1688 or ’89 bought the former Bedlow grant, the largest single holding in Bloomingdale at that time. Persons in household: 15. Rebeccah Van Scyock = Rebecca Van Schaick, widow of Adrian van Schaick, keeper of a well-known tavern near today’s Astor Place, who died in 1700. She bought Lot 6 from the van Brugh heirs prior to 1701 and already owned Lot 7 through her husband, who had bought it in 1797. In 1701, she sold lots 6 and 7 to Cornelius Dykeman, but may still have been living on the property in 1703. Persons in household: 5 Oronout Waber = Aernout or Arnaut Webbers, owned land just north of Wolfert Webber. According to the website Gene, Aernout was a brother of Wolfert but the site also says he died in 1694 or 95. The one found on the census may have been a grandson or nephew. Persons in household: 4. Wolford Waber = Wolfert Webbers. He married a daughter of Jacob Cornellisen Stille in 1697 and purchased a farm from his father in law. He was probaby a son of the Wolphert Webber who received a grant of land on the Lower East Side from Stuyvesant in 1650. Stokes identifies the Bloomingdale property as the Wolfert Webbers Upper Farm. Persons in household: 4 The households of the people identified above total 46 people, with an average per household of 6.7. However, it is likely that at least some of the dozen unidentifiable Out Ward households were also located in Bloomingdale. Since roughly a sixth of the identifiable households were in Bloomingdale, let us assume two additional households with an average of 6.7 people per household. Thus, if we rely on this census, we can estimate the total population of Bloomingdale in 1703 at approximately 60 people. However, It is important to take into account the historical context of that census and its possible defects. In the preceding year, 1702, an outbreak of yellow fever grew to be the worst epidemic in New York City’s history in terms of the proportion of population killed. As the provincial governor, Lord Cornbury, wrote on September 27, “In ten week’s time, sickness has swept away upwards of 500 people of all ages and sexes.” The death toll represented fully 10 percent of the city’s population. Also in 1702, a new conflict had broken out between England and France, and New Yorkers once again found themselves under threat of invasion from Canada. Lord Cornbury, who had arrived in New York in May of 1702, immediately set about rebuilding New York’s defenses. A major concern, especially in the wake of the epidemic, was military manpower. On November 27, 1702 the legislature passed an act fixing the draft age as between 16 and 60. On January 29, 1703, Queen Anne signed a lengthy set of instructions to Cornbury including an order to make an annual report of the population including the number “fit to bear Arms in the Militia.” Thus, the immediate purpose of the Census of 1703 was to identify men available for conscription. This is evident from the first column of the census table, headed “Males from 16 to 60.” Given its purpose, the census takers were unlikely to have been met with enthusiasm. The General Assembly acknowledged as much in an address to Governor Cornbury on May 27, 1703: “The late war, drained us of the greater Part of our Youth, who to avoid being detached to serve on the Frontiers forsake their native Soil, to settle in the neighboring Colonies.” Thus, the census results shown in the table may have been depressed by a tendency of young men to make themselves scarce; of residents to fudge the number and ages of male household members; and of householders to be less than forthcoming about the whereabouts of neighbors. While twelve of the names on the 1703 census list are unreadable, it is nevertheless curious that the list includes so few names that one would expect to find among a list of inhabitants of the Out Ward in 1703. Those are the names, or at least surnames, of ward officials who were elected annually from among actual residents. Among those one would expect to find, all of which are recorded in the Minutes of the Common Council for their respective years, are Hendrick Cordus, Collector of the Bowery Division in 1703; Abraham Boeke, Assessor of the Bowery Division in 1702; Jan Brevoort, who was Assistant Alderman in 1702 and also appointed Pound Keeper for the Bowery Division in that year; Jan Cornelisse, Constable for the Bowery Division in 1702; and Jacob DeKey, Alderman of the Out Ward in 1702 and 1703. We do not find any of the Meyers of Harlem, although Adolf Meyer was its Assessor in 1703 and Johannes Meyer its Constable. Nor do we find any of the Waldrons of Harlem, although Barent Waldron was Overseer of Highways in 1702 and 1703, as well as Collector in the latter year; and Samuel Waldron was Assessor in 1702. Could these well-informed public officials have somehow avoided the census takers? Or did the census takers, for whatever reason, fail to count them? The answers to these questions may be found in documents yet to be unearthed in the New York State Archives and other collections in the U.S. and Britain. In the meantime, assuming the 1703 population count was affected by census avoidance, how great could the undercount have been? I believe an undercount of 25 percent is plausible. If that percentage is applied to Bloomingdale, its estimated population would be increased to 75. That is still a very sparse population for an area of three and a half square miles on the island of Manhattan. The recipients of the 1667 “syndicate grant” had divided its 1300 acres into 12 lots, each large enough for a farm of respectable size. As of 1703, Teunis Ides’ grant of over 400 acres had not yet been divided among his children and their spouses. Two additional grants covered what is now Morningside Heights. Thus, there were a total of 15 parcels. The small number of households identified in the 1703 census suggests that as many as half of the Bloomingdale parcels were unoccupied and still being held as speculative investments by absentee owners. The unoccupied parcels were not necessarily without economic use. Bloomingdale, in its natural state, was heavily wooded. Absentee owners could have profited for years from the harvesting of timber, a seasonal activity that could have been carried on by crews living in tents or other temporary shelters. Once cleared, all or parts of the land could have been rented to neighboring farmers for cropland or pasturage. Cleared land could also have been used for orchards, which could also be tended and harvested by seasonal labor not requiring permanent shelter. Such seasonal labor would not have affected the resident population count. Even taking into account the defects of the 1703 Census, it is likely that the entire population of Bloomingdale in 1703 did not exceed 75. THE ADVENT OF THE BLOOMINGDALE ROAD On June 19th, 1703, the New York General Assembly enacted a law providing for the “laying out, regulating, clearing, and preserving common highway through this Colony.” Three commissioners were appointed to lay out highways in the County of New York—i.e., Manhattan—and within 18 months to “make return to the clerk of the County a full and perfect report and description of the manner and extent of every road laid out by them.” The deadline was twice postponed, but as eventually filed and recorded, the report described four routes in New York County. The first, beginning at about the present Broadway near Fulton St., went north via the Bowery and the Eastern Post Road, to Harlem; the second went from Harlem to the Kings Bridge, mostly following the ancient Indian trail to Spuyten Duyvil; the third was a road from the Bowery westward to Greenwich, most of which is now Greenwich Avenue; and finally a road to Bloomingdale. That name is not used in the commissioners’ report, which describes the eventual Bloomingdale Road as follows: “ From the house at the End of New York Lane, there is likewise to lye a Road turning to the left hand the course being northerly and so by Great Kills & forward as the said Road now lyes unto Theunis Edis’s & Capt. D’Key’s through the said Edis land.” The New York Lane was the northerly extension of the Bowery, which is now part of Broadway where it crosses Fifth Avenue at Madison Square. From that point, the commissioners may have had to map an entirely new route through the network of streams feeding into the Great Kill. But once beyond that, the phrase “forward as the said road now lyes unto” Theunis Edis’s land suggests that there was an existing road of some kind. This might well have been an old Indian trail, or might have developed out of paths beaten by settlers and their livestock in moving between farms. Thus, there were rural roads, however rough, in Bloomingdale well before 1707. An improved road through Bloomingdale was very desirable. It would make it easier and faster to move goods, using bigger and better carts and wagons. In time of war, it would enable faster movement of troops and their equipment. Widening and better grading would make the road safer and more passable for horse drawn carriages. It also made the adjacent real estate more attractive to the class of people who could afford to travel in horse-drawn carriages. However, significant road improvement was not feasible without assurance that everyone along the road would be legally bound to contribute to its construction and upkeep. Giving it the status of a provincial highway was the legal mechanism to assure this. The Bloomingdale Road was laid out to a width of four rods or 66 feet. The surveyors marked out two parallel lines, using stakes in the ground or blazes on trees. This was not the width of the roadway, but the width of the right-of-way, the line at which farmers could place their fences. The actual cleared path was a fraction of that, probably no more than 15 feet in most places. This made sense because the road—unpaved, of course—was subject to rutting, flooding and washouts. There had to be room to shift the alignment on short notice. There also had to be space to make repairs, build embankments or dig drainage ditches where they were needed. The road was expected to be maintained by the people living along it through a system of conscripted labor. Overseers were appointed for each district, with the power to compel people to work on the highway for a certain number of days per year, or to provide substitutes, under penalty of a fine. As it turned out, the work of maintaining the road was excessively burdensome for the inhabitants of the Bloomingdale district, with its relatively small population. In 1751, the legislature, in an act specifically to address the maintenance of the Bloomingdale Road, reduced the right-of-way from four rods to two. The road did have the effect of increasing land values and changing the social character of Bloomingdale. In 1707, Bloomingdale was still predominantly an agricultural district. A major shift came with the arrival of Stephen Delancey, one of the richest and most socially prominent men in the colony. Sometime between 1720 and 1729 he acquired the former Lots 8, 9 and 10 of the syndicate’s grant, amounting to about 300 acres, and established a country estate that he called Bloomingdale. Also in 1729, he acquired the former Lots 3, 4 and 5, which he called Little Bloomingdale. The presence of the Delancey estates gave Bloomingdale a social cachet that attracted other landed gentry-- or would-be gentry-- for several more generations. The Bloomingdale Road was an important determinant of development in Upper Manhattan. It would have been obliterated by the Commissioner’s Plan of 1811, but by that by time so much had been built in relation to the Bloomingdale Road that it managed to survive. With minor tweaks of alignment, the Bloomingdale Road is essentially today’s Broadway from 23rd Street to 107th Street. The squares created by its intersections with the grid remain some of the liveliest and most interesting places on Manhattan Island.

1 Comment

|

||||||||